“Long intros are practically illegal in pop and rap because nobody wants their song to get skipped when it comes on,” writes New York based producer umru (aka Umru Rothenberg) via email about digital platforms and how they’re shaping the sound and format of pop music. “I don’t really know what my stance is here. I certainly don’t think music should be written for the algorithm but it’s also a fun experiment to see how far that stuff can be pushed and exploited in one’s favor.”

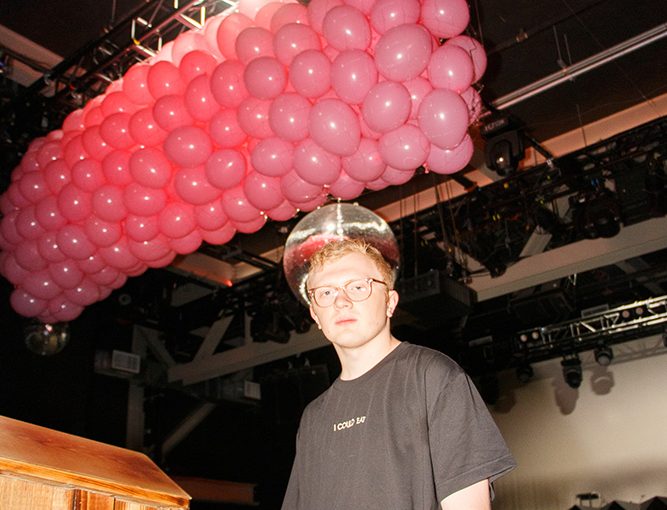

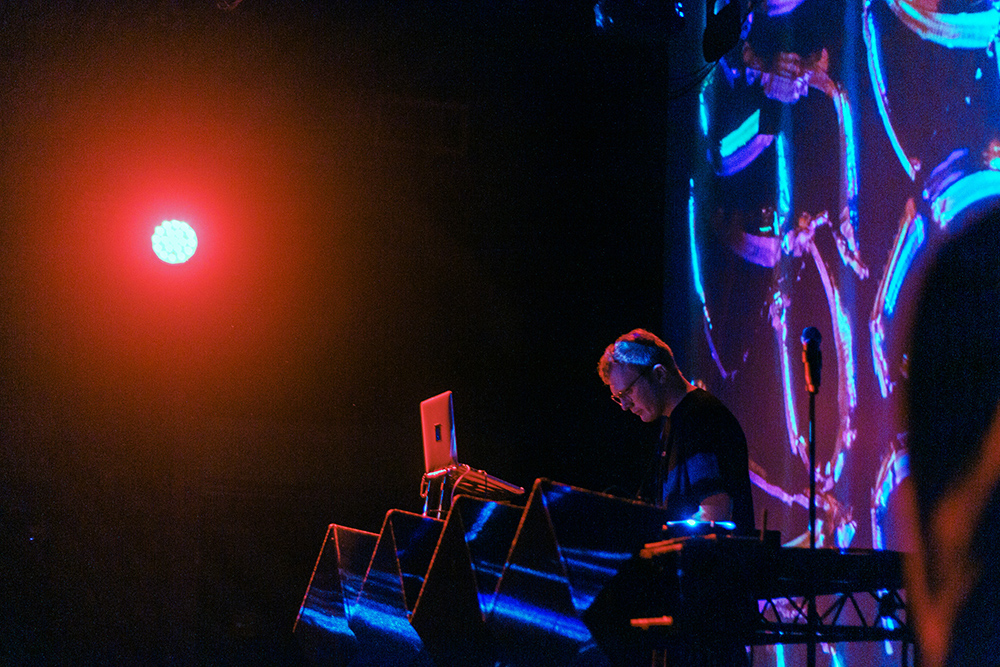

Corresponding in the lead up to his DJ set at Berlin’s Trauma Bar und Kino for Creamcake’s 3hd 2019: Fluid Wor(l)ds festival, umru has found his footing amongst a new wave of online pop. He emerged from a scene of beat-oriented producers on SoundCloud, pushing high sheen futurism that’s circulated the platform for years through the likes of Sinjin Hawke into weird and warped disassembly. After signing last year to PC Music, umru’s 2018 debut EP search result finessed a style that alternates between lush hoover synths and sparkling headphone-optimised atmospherics, while clashing against metallic drops. It’s a sound that can be heard in his livestreamed DJ sets for virtual festivals on Minecraft, or on his productions accompanying a new generation of digitally native, independent pop idols such as Kim Petras, Tommy Cash and Dorian Electra.

From bedroom uploads to pop virality, umru’s trajectory as an artist encapsulates gestational shifts in contemporary pop within the digital mediascape. His career comes from a still growing field, where content creators, viral videos and the algorithms of social media platforms have as much influence on the evolution of the musical mainstream as record labels and big production teams. This is something umru himself is keen to toy with, as he notes: “We’re in a really fun moment where the formula hasn’t really been figured out by anyone yet.”

It’s fitting then that our interview happens through Gmail, with the artist taking the time to discuss topics spanning changing cultures around pop and the makings of an online scene, technology and TikTok.

**I’m so interested in the Minecraft festivals you and your friends put together. It makes me think about older DIY music cultures that took place remotely in people’s bedrooms (through zines and cassette labels). It’s intriguing and new in this context of club music and more IRL cultures of live gatherings. What do you think the internet has done for dance music?

Umru Rothenberg: The club has just gotten bigger! Events in the vein of our Open Pit Minecraft festivals aren’t really a replacement for live music. They’re more of an alternative for the many who, for location, health or financial reasons, can’t attend or feel comfortable in a club to hopefully experience some level of that same feeling. [That’s] not only as listeners but also performers—we’ve tried to always highlight performers who might not get a chance to be heard at an IRL venue. It also means everything doesn’t have to be limited to danceable ‘club’ music but it’s surprising how authentic of a live experience DJs at our events have been able to pull off in their sets, with voiceovers, crowd noise, or starting in-chat crowd chants.

**I’m thinking a lot these days about pop music and online formats. Do you think after certain songs have done so well from TikTok and viral challenges that we’re heading to a place where artists think more and more about the culture around a pop song, or ways that it can be circulated online? Like coming up with hooks with meme-ability in mind…

UR: This is definitely huge now, artists and labels are literally picking song titles for SEO, and shortening songs so listeners are more likely to repeat them. What I love about TikTok and that whole world right now is how hard it is to predict. Labels can throw a lot of money at getting songs to go ‘viral’ but in the end it’s literally kids who are influencing what happens.

The artists getting to the top of the charts through TikTok don’t always have lots of money behind them, more of my friends have gone viral in the past year than ever before—ABSRDST and Diveo, 100 gecs, Y2K and bbno$, Ashnikko… TikTok certainly has its problematic sides, from predators to dodgy copyright claims, and I don’t know if it’s really good for music as a whole, but at the very least it’s throwing a wrench in how the industry is supposed to run and allowing some crazy stuff to happen.

**You’ve mentioned in an interview your interest in not simply making ‘producer music’ but rather in influencing the mainstream. What do you think constitutes pop music, and where would you like to see it heading?

UR: I come from the SoundCloud beat scene world where the goal always seemed to be to impress other producers, but I think many from that world have realized those same techniques can be more interestingly applied in the context of popular music. There’s always been a divide between pop as a defined genre and simply meaning whatever styles and musical tropes are currently popular. More than ever right now, it can really be anything, but I definitely would like to see it continue to become less restrained and dictated by norms and the traditional label-driven models. I think the ‘sound’ of pop music will naturally change as this happens. There’s already much more experimental and abrasive production right at the forefront, from producers like SOPHIE or Flume gaining mainstream popularity to totally clipping rap songs, even 24/7 lofi hiphop beats to study to. It’s all stuff that would be hard to imagine as pop not that long ago.

**What are your thoughts on what it’s like as an artist these days having your musical evolution happen very publicly online from the beginning?

UR: Oh it kind of sucks. I’ve gone through many phases of deleting old SoundCloud uploads etc; I’ve got plenty of embarrassing stuff online. I mean, I identified myself as a SoundCloud Trap Producer. I had my share of Japanese kanji on cover art, and so on. At the same time, I like that people can see the growth of my music to some degree and the only reason anything has happened for me was because A. G. Cook found a quick Tommy Cash remix I posted on my second SoundCloud page. So obviously I can’t say it’s a bad thing that for a few years everything I ever made was shared so publicly.

**Tell me a bit about the community of underground artists you work with, like Laura Les. Is your scene evolving as you’ve joined the PC Music fold?

UR: It’s definitely a world that’s constantly evolving, but most interestingly my online ‘scene’ isn’t made up of especially similar artists—look at the hugely varied sound of the Open Pit Minecraft event lineups. There’s definitely every possible style of electronic music being played, plus a literal metal band (Polyphia), a full ambient noise set from Eden, and so on. It’s much more of a community than a specific sound. Laura Les, especially her project with Dylan Brady, 100 gecs, provides a perfect example of this world that contains as many of these musical styles as possible. Every music journalist I’ve seen attempting to describe their album names totally different musical styles as comparisons.

As for PC Music as a label, they’ve always been a very closed group of friends who have consistently been inspiring the wider online community of experimental pop and electronic music. I was really surprised to be asked to release with them but it’s slowly expanding to a number of artists who are new to the label, from Estonian rapper Tommy Cash to French band/pop writing powerhouse Planet 1999.

**I’m sure a lot of pop artists these days write with streaming platform algorithms in mind. How do you think they affect the pop music writing process, and is this something you try and push back on?

UR: I mentioned this a few questions back but it’s definitely happening. I’m pretty sure all those 6ix9ine songs named ‘KOODA’ or whatever are purposefully unique search terms. I know producers who’s lofi hiphop side projects make them thousands more dollars a month than their ‘real’ music while being relatively unknown, just because people put on those playlists literally while studying without paying attention to the artist names. As much as ‘The Algorithm’ represents another way for streaming services to maintain control of what gets listened to, there’s also something egalitarian about it. You can’t (I don’t think, yet) directly buy your way to the top of algorithm results the way you can to some curated playlists. It’s not perfect and certainly favors certain styles and techniques, but it also provides opportunities to get heard for some artists where there previously weren’t any.**