In Italo Calvino’s The Petrol Pump, a man thinks about the oil he’s filling up his car on a country roadside. He writes, “there’s a deep silence, as if all engines everywhere had ceased their firing and the wheeling life of the human race had stopped. The day the earth’s crust reabsorbs cities…until in millions of years’ time it thickens into oily deposits…” Although it seems benign— almost trivial— Calvino uses this experience to call attention to the totality of oil extraction. It illustrates the temporal and ubiquitous quality of oil and its trade industry, the focus of Maryam Monalisa Gharavi and Sam Lavigne‘s ‘OBIT’and ‘Oil News 1989-2020’ for Sonic Acts 2022 Biennial exhibition, one sun after another.

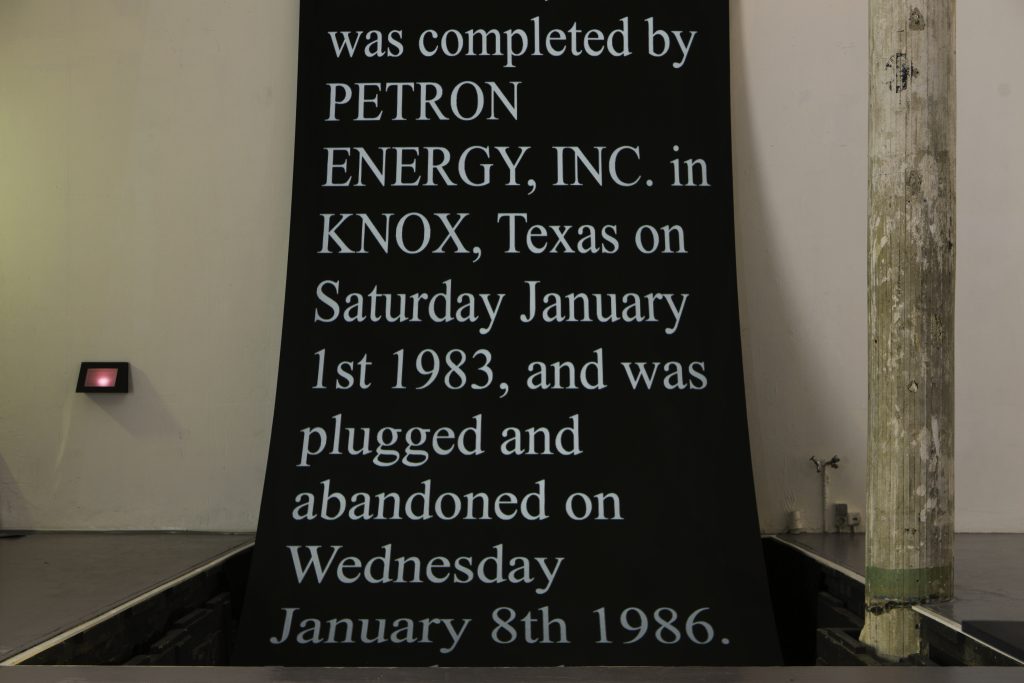

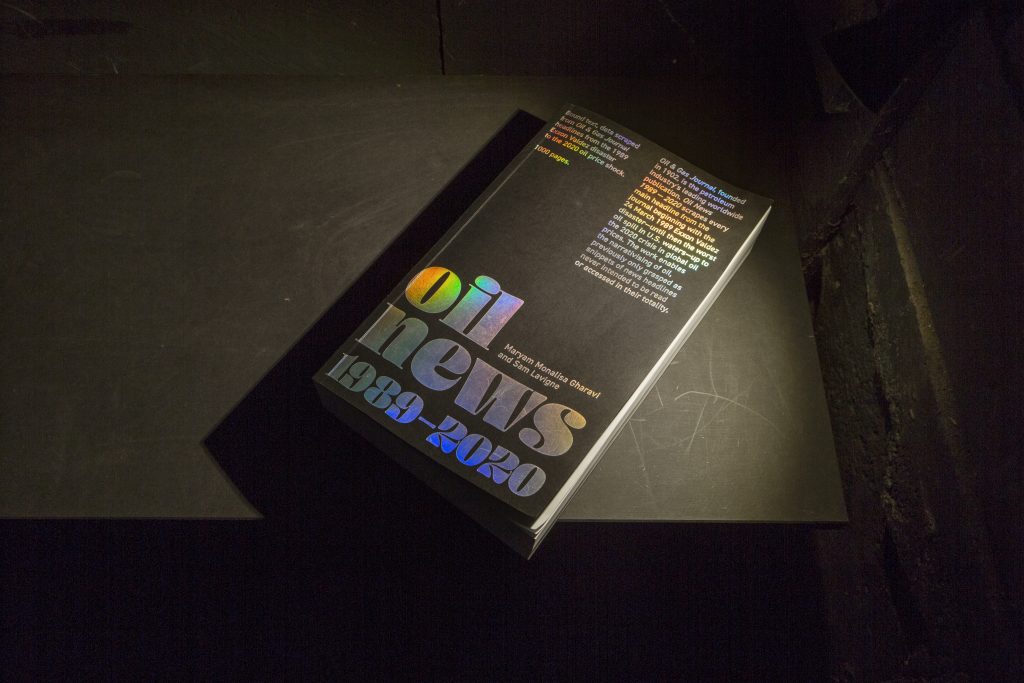

Running from September 30 to October 23 in Amsterdam, one sun another draws upon Timothy Morton‘s notion of hyperobjectivity in its depiction of universal and interconnected environmental conditions. In this vein, Gharavi and Lavigne’s works explore the oil industry’s omnipresence in the United States. Oil News 1989-2020 documents reported incidents of oil spills, while OBIT is a collection of oilwells in that have been plugged and disbanded. Together, these works attempt to scale the sheer magnitude of oil extraction from ecological and infrastructural perspectives. I spoke with both artists to learn a bit more about the project, Lavigne’s practice of scrapism, and how data bind a story about oil they seek to reveal.

**You’re sharing OBIT and Oil News 1989-2020 for Sonic Acts. Can you tell me how these projects started? How do they relate to each other?

Maryam Monalisa Gharavi: Back in 2019, I had just finished a residency called Dirt & Debt in New York City. And I’ve been thinking a lot about the contiguous industries of oil and data after the very famous quote from British mathematician and Tesco loyalty card founder Clive Hornby who said, “data is the new oil .”I wondered what it would be like to galvanize a collective to look at these things in concert with each other. I conceived it at that time as a mean in a bit of a cheeky but serious way as a one-woman collective called Oil Research Group, otherwise known as ORG.

Sonic Acts had its first at-home residency, and I proposed this project called ‘Exhaust’ that would really look at everything from dirt, data in contiguity, and burnout culture, which was also rising at that time. What does it mean to take things to their asymptotic limit in terms of extractive economies in terms of human resources, of course, exacerbated by the pandemic? At that point, ORG started to become much more collaborative. It allowed me to put together a round table in which oil and data were discussed in tandem with each other. At the home residency by Sonic Acts, I approached Sam and said, “you know, there’s got to be something we can do with the wealth of data that oil engenders online; there’s something, there’s something that we can dig here.”

We started amassing these databases, and gradually—and maybe I’ll let Sam discuss this further— I started thinking about the ways that we can organize this information. For a long time, the tentative title for these works was Oil Scraper. It was like the thing that kept them all together. OBIT has to do with public databases of American oil well deaths, of which we’ve counted over 314,000, and Oil News 1989-2020 looks at the way the petroleum industry itself, keeps a record keeps a public record of all the news that’s fit to print.

**One thing that stuck out to me with what you were saying is this idea of oil and data taken to their asymptotic limit. What are the implications of that?

M: I think the idea comes from within the materiality of oil itself. What I mean by that is I really set out to test my own assumptions. Among those assumptions, of course, is the finitude of fossil fuels. Even though we live and we engineer our lives as though there is an infinitude of resources, there’s an assumption that they are finite. On the other hand, you know, this time in my life, I was teaching data and privacy at NYU. It was clear from the cannon that the presumption about data is that it is infinite; that it is without limitation. That’s testable in the fact that we are having our data scraped or our data extracted all the time, that even when a Twitter user dies or closes their account, there’s still metadata. Facebook still asks you to memorialize your Facebook account so that someone else will take it over. There’s metadata or storage sets, storage sites for metadata, in a physical way, all around the United States.

These two opposites were really sticky to me that, on the one hand, fossil fuels are presumed to be finite, and data is infinite. So, what does that mean? That makes oil and gas very precious, although looking at human economies, you wouldn’t assume that to be true by the way that we expend them and speculate on them. And on the other hand, that data is without limit. It’s infinite.

**Sam, what was your role in carrying some of these ideas?

Sam Lavigne: I’ll just start with a description of this thing that I do in my own practice that I’ve been calling scrapism, just so that there’s some useful background information. I became really interested in this idea of web scraping as an artistic or cultural or critical practice which is something I call scrapism. A lot of the work that I do begins with writing a web scraper and doing this process that I’ve begun to call databasing: looking at a website and figuring out what data the website has. The question with web scraping is how to take those databases and remake them on your computer. Perhaps some truths can come out; perhaps something can be revealed about that process. It’s also like a process of shifting a power dynamic, right? Because power on the web is related to who has read and write access to the databases that constitute it.

When Monalisa approached me about this project, we knew that we wanted to do some web scraping. I think we didn’t quite know what specifically we should scrape. We were looking at getting a list of every single oil well that exists in the US. Let’s get every single headline about oil that we can find, let’s get every single job, every single job about oil that we can find. We ended up with two parts, just to be clear, the database of oil wells and then this database that we put together of oil news. For the oil well database, we looked specifically not in every single oil well but at wells that were dead, the plugged-in abandoned wells.

**Would you agree that scrapism is an extractive process? I think that’s interesting in the context of this conversation.

S: I mean, I think it’s important context to realize that all these extremely valuable internet companies either started out as web scraping companies or continue to be web scraping companies, right? Google is a web scraping company. Same with Facebook. So, these are the core of a lot of these big businesses, which are highly exploitative and extractivist. There are also companies like ClearView AI, which is a quite terrifying facial recognition company run by someone who’s on the extreme right. They sell their services to police departments. Obviously, web scraping can be used for other purposes, too. Journalists use it a lot. The goal of scrapism as an articulation of the practice is to sort of flip the script and think about the ways in which sort of those same techniques can be leveraged for radical politics.

**I was wondering if you could connect that to what Monalisa said earlier.

S: I mean, there’s a few things here. When you look at these datasets, the first thing is they’re not really meant to be looked at by people in a lot of ways. So, there’s something immediately interesting that happens when a person just looks through them all. And obviously, it would be quite difficult and unrealistic for someone to sit through and read the obituary of every single oil well in the US, right? It probably takes you like a week without sleeping, right? Something like that, maybe a little bit more.

It’s sort of the same thing with Oil News. Like, even though clearly a human is meant to read the news, there is a way in which a human is not meant to read the entirety of Oil News in chronological order. It’s almost like a hyper-objectivity aspect in some ways where you have this thing affecting and engendering reality, but we can’t necessarily like even comprehend it.

M: I think the question of visibility, about that totality comes to mind because, like he’s saying, they weren’t meant to be seen this way. There’s this assumption about oil that it’s always slipping past our visibility. And yet, it isn’t. Maybe if I’m at the gas station, but in another way, the number one index of the economy are those marquee gas prices. Data is essentially a collection of digitized information. It wasn’t really ever meant to be seen as a story. Our work in OBIT and Oil News isn’t particularly visible, meaning it’s not iconographic. It doesn’t show oil. There are no pictures of oil workers and oily jobs and news tickers. It’s presented as white text on black backgrounds, one in like a physical install and one in a book that you could hold in your hand. But it points to that totality that was never meant to be totalized.**