Far from lamenting the loss of the printed word, online reading has more or less superseded the need to read on paper. When the ‘paperless office’ was merely a tech-utopian environmentalist fantasy, the possibilities of a world without logging seemed feasible with the dawn of the Internet Age. Of course, social stratification, the anxieties over carbon emissions connected to online servers, and the colossal e-waste of discarded computer hardware — alongside exploitative and destructive marketing strategies of planned obsolescence — has done nothing to diminish the problem of pollution (and climate change) within capitalism.

All this, while the condition of online cultural production necessitating constant circulation has left contemporary discourse and media with the problem of, ‘where will all the knowledge go when it stops moving?’ There are a few publications trying to combat this global anterograde amnesia for recent history by printing books, journals, catalogues, that refer to the transient, interrelated and rhizomatic state of information existing on the internet.

These attempts include a new publication called Screen Shot with its remit of “freezing moments in the city’s history” into the linear timeline of a journal. It offers conceptual ‘screen grabs’ from the last six months in developments in socio-political and contemporary art discussion in the London event calendar. Meanwhile, a journal called Picnic Magazine in Israel, compiled images from the online and the outside into beautiful, carefully-curated anthologies for five volumes between 2007 and 2011. It finally succumbed to the success of Tumblr, which was rapidly expanding its reach at the same time.

With that in mind, you might assume this drive to hold on to the past is futile, especially in the face of accelerated capital, but also as a desire as old as time — eternal life. But, in combining new and old formats for presenting and preserving art and ideas, an interesting dialogue emerges about what counts, who decides and when it is time to move on.

Here are some ways printed publications have emerged from an awareness of the internet:

A modern experimental, avant-garde biannual journal The Happy Hypocrite is led by new writing. The series is published by London-based artists book publishers Book Works, and edited by Glasgow-based writer and critic Maria Fusco while focussing on realising otherwise uncategorisable modes of textual and research-based projects by artists, writers and theorists.

Recent publications include artist, writer and film-maker Sophia Al-Maria’s ‘Fresh Hell’ for its eighth issue and concerning the ubiquitous role of oil in the world with old posters, a Tumblr account, essays, unexplained images, stories and biographical accounts by the likes of Monira Al Qadiri, McKenzie Wark, Stephanie Bailey and Abdullah Al-Mutairi. The latest, ninth edition #ACCUMULATOR_PLUS is guest-edited by London-based artist Hannah Sawtell who explores how sound and text interrelate and interact, extending its broadcast to a radio show.

Collated into eight loosely-themed sections, including ‘Locating Performance’, ‘Performance Under Attack’ and ‘High Art in Low Places’, among others, The Live Art Almanac is a selection of ‘found’ articles about live art and radical performance-based practices. It’s published by Live Art Development Agency (LADA) and Oberon Books, and features recent writing on these subjects that have been “published, shared, sent, spread and read.”

Last year’s Volume 4, featured writing by Derica Shields, Coco Fusco, Morgan Quaintance, Vaginal Davis and more on work by artists including Mykki Blanco, Wu Tsang and boychild, published between January 2012 and December 2014.

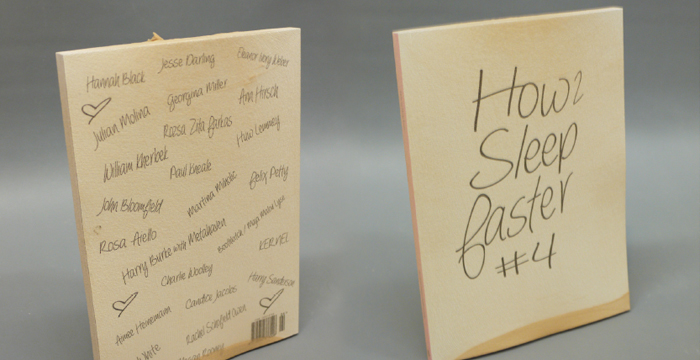

Also a compilation of works and writings, sourced and commissioned by international artists and writers, independent London gallery Arcadia Missa‘s publishing arm has been compiling some of the most exciting art discourse with its annual How to Sleep Faster journal. Each issue poses a different socio-political question relevant to the emerging artists of the day, including ‘How is survivalism mediated in contemporary culture? . . .’ in Issue #3, ‘What now is a radicalised, networked, subjectivity?’ in Issue #4 and ‘What are the politics of refusal?’ in Issue #5.

Past contributors have included Jesse Darling, Jaakko Pallasvuo, Huw Lemmey, Ann Hirsch and Cristine Brache, while the most recent Issue #6 from 2016 asks “Can sex be a site for identity politics, after we are imbued with the lore and failure of the sexual ‘revolution’?” and features contributions by Kris Lemsalu, Morag Keil, Aurelia Guo C.R.E.A.M., and others.

No Internet, No Art – A Lunch Bytes Anthology

No Internet, No Art, published by Eindhoven’s Onomatopee, followed the conclusion of the European edition of the Lunch Bytes programme of discussions, conferences and resources that ran from 2014 to 2015. That series, examining the role and consequences of digital technologies in the art world, followed an earlier American Edition that ran from 2011 to 2013 and is compiled here by curator and editor Melanie Bühler.

The book, thick with content, mimics the white browsers and infinite scrolls of the online space with a collection of essays, interviews and images by key contributors, including Elvia Wilk, Adam Cruces, Paul Kneale and Kenneth Goldsmith. They’re all numbered and ‘linked’ to a corresponding index page and the content pages come in two columns with arrows pointing to separate, though related streams of ‘Commentary’ and ‘Contributions,’ in a web of rhizomatic relationships bound together by a book.

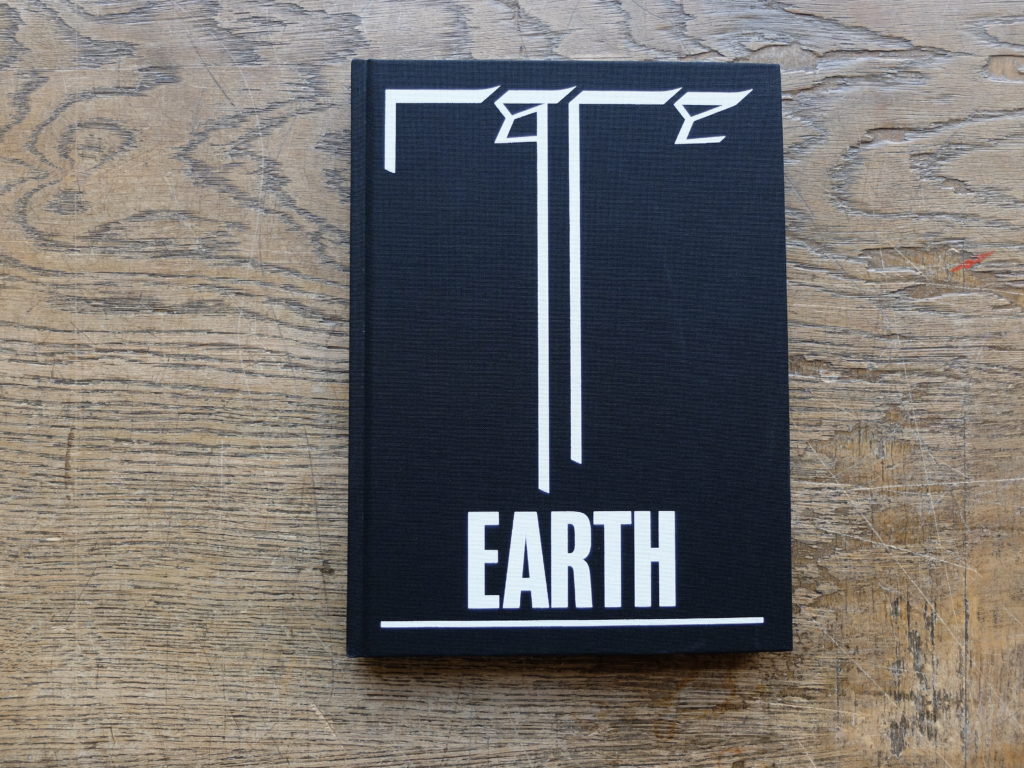

Designed by Raf Rennie and David Rudnick (the latter of whom, incidentally, is also responsible for aqnb‘s recent site relaunch, along with Harry Bloom), Rare Earth is an excellent example of where concept, content and design intersect. The writing accompanies images of art works from the exhibition of the same name, co-curated by Nadim Samman and Boris Ondreička in 2015, concerned with rare earth elements and their indelible impact on the modern world.

Following the periodic table of these chemical components, a series of complex systems of thought are dispersed and constructed into objects, with implications that go well beyond the physical form. A black book cover embraces its red and Scandium silver pages of exhibition images, including the work of the likes of Iain Ball, Camille Henrot, Marguerite Humeau, and Arseniy Zhilyaev, alongside speculative realist, accelerationist, object-oriented and new materialist texts by Timothy Morton, Jane Bennett, The Otolith Group and many more. The catalogue is published by Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary (TBA21) and Berlin’s Sternberg Press and boasts a basic black type that almost shimmers.

A self-aware title for a print-based project, published by Nottingham’s Landfill Editions, the Mould Map series takes contemporary socio-political issues as the basis for selecting relevant artists working within a chosen theme. Their fourth 2015 edition, ‘EuroZone SpeZial,’ was a foreboding look into the European Union’s precarious future via 30-plus artists and collectives — including Ed Fornieles, Amalia Ulman Yuri Pattison and Martti Kalliala — each defined by their country’s ISO code (e.g., ‘SE’ for Sweden, ‘GB’ for the UK, and so on).

The most recent Mould Map 5, from mid-last year, was called ‘Black Box‘ and worked with topics like “Conspiracy, tactical confusion and counter-intel” and “False flags, dark ops and black magik,” and included the work of the likes of Brenna Murphy, Parker Ito, Julien Ceccaldi, and Daniel Swan among them. We’re looking forward to what they come up with this year.**