Berlin’s TLTRPreß has released the latest issue of The Yap, first printed in March, with an excerpted interview from the zine re-published on AQNB today.

Led by Ondřej Teplý, The Yap’s 77th edition addresses printed media in the digital age, musing, “can publishing projects also experience a mid-life crisis?” Focussing on the subject of independent presses from the perspectives of a writer, book designer, and a performance artist, the project features interviews with Habib William Kherbek, Monika Janulvičiūtė, and Ivan Cheng, who discuss their recents projects and experiences working with publishing houses such as TLTRPreß.

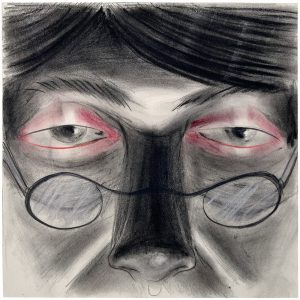

In an interview with Habib William Kherbeck, up today on AQNB, the writer and author discusses techno-feudalism, the physicality of digital media and his TLTRPreß book STILL DANCING. A collection of poems and prose pieces relating to his 2018 photographic work of the same title, STILL DANCING explores the idea of dance as an intersection of discourses, themes, and forms. The interplay of different types of media, and highlighting the pervasiveness of politics both in art and everyday reality, are the typical features of Kherbek’s work. He has published books including the novels Ecology of Secrets (2013), Best Practices (2021) and the short story collection Twenty Terrifying Tales From Our Technofeudal Tomorrow (2021) through Arcadia Missa.**

Read the excerpted interview below and see the previous interview in the series with Ivan Cheng on AQNB.

—

Ondřej Teplý: Before we start, I would like to ask you if you know whether or not Yanis Varoufakis knows about your essay ‘Techno-Feudalism and The Tragedy of Commons’ from 2016, because I recently noted that it’s so ‘his thing’ right now?

Habib William Kherbeck: No idea — though almost certainly not. But yeah, it’s his thing. Get it on the record: he’s four years after me! Haha. He’s catching up, and he needs to know! But, also, thanks to him it’s definitely in the air now, which is good.

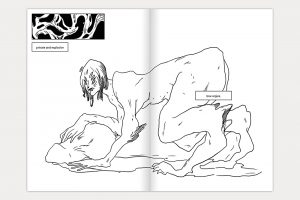

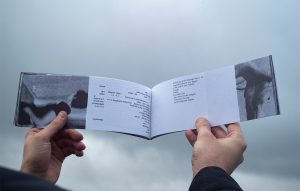

OT: Okay, let’s start with Still Dancing. You’re the editor of the book. The first thing that caught my attention is its design. Its long, slim format reminds me of a kind of colour catalogue. Additionally, it’s flippable so you can read it from both sides. How does such a format, without any clear beginning or end, serve the topic of the book which is dance and performance?

HWK: Well, the design is a bit of a reference to the infinite scroll of the Internet. It never ends or begins, just like this book. On the other hand, dance is a time-based medium. It has a temporal dimension, and even in this book, it takes time to flip through one way or another, but the time isn’t contained; the time is essentially external. It’s as internal as you want it to be. You can pace it and move it in your way. Essentially, you can choreograph it.

To catch the ephemerality of the dance [by Leah Katz] was a challenge. The dance happened one day, one afternoon, and the people who saw it saw it [posted to my Instagram] and they had a certain experience that isn’t generalisable. To have a record of the dance performance, I took pictures of it with my phone. The result doesn’t portray just the dance, it shows, as well, the limits of the technology.

OT: Still Dancing is a collection written by several authors. How did you pick them? Did you set any requirements for participation in the book? I ask because, as you mentioned, the content, and especially the design, is inspired by infinite Instagram scrolling and Web 2.0.

HWK: Alexis Calvas, I knew her from a talk she gave at the University of Arts in London [she also co-edited the magazine Strike]. Sydney Beaumont, I knew her from the Berlin art scene, but she’s based in New York right now. Kitty Ray Harper Fedorec is a friend of a friend and she was introduced to me digitally. M.E. Gray is somebody I’ve known a long time from back in London. Mina Khanlarzadeh I did some editing work for, and Greg Nissan is an art writer and journalist. A lot of these people are poets, some of them write about dance, like Kitty, and some even have a deeper experience with dance, like Alexis. She’s a trained dancer. I was interested in bringing together different perspectives.

The idea behind this project was to use the visual language of the Internet, but use it in a way that only a book can and that the Internet can’t. Through the design, which Monika Janulevičiūtė did amazingly, we integrated the text and the image in a way that is reinforcing. You can experience them simultaneously, at your own pace, in a way that the Internet doesn’t allow you to do.

OT: We previously mentioned ‘Techno-Feudalism and The Tragedy of The Commons (2016). In the essay, you’re pointing out that late capitalism transformed itself — thanks to the platformisation of the economy — into a system that more resembles feudalism. What is or will be the role of independent publishing projects in such a society?

HWK: It’s a good question. I’ve been thinking about this because knowing how challenging it is to sell books as an independent press you end in these two kinds of tensions, right? Do you just become more and more niche and you cater to this existing audience, or do you try to reach out to more people? The dynamics of the markets are exerting pressures. Back in the day, magazines existed for getting advertising to people, and advertising was the main revenue generator. Now, that’s still probably the case for most glossy magazines. The big publishing houses are essentially vectors for selling a bestseller, and everything that happens on the side of that is incidental. But the idea with the smaller [publishers] is that you can’t compete with the big ones; you can’t use that model — and sometimes even those companies can’t use it anymore. Now, it’s all about events.

New Yorker or Vogue events ‘present’ this and that. They became brands, and they disembodied from the objects that people buy. The magazines almost advertise the name in a way. In a certain sense, some of these small publishers are already there. People know there’s gonna be a certain kind of book from TLTRPreß or Arcadia Missa or If a Leaf Falls Press — [those are] the names of places I’ve worked with — they have a certain identity, and that identity can be useful but it can also be somehow limiting in markets where you’re under a constant pressure to produce, to constantly generate stuff. I think it’s going to be a challenging environment going ahead, particularly, as you know, digital media still sucks the energy out from other forms. Like the NFTs psychosis now. That’s where the momentum is. What I like about projects like TLTRPreß and Arcadia and If a Leaf Falls is that they are extensions of artistic projects. They have a little bit more freedom, a more of an experimental spirit to question those things. The value they bring is to pose questions about what is possible now. Unfortunately, they’re facing a pretty unforgiving market.

OT: Also paper, a medium which is by many considered obsolete, is currently for self-publishing purposes less restrictive than the Internet, the symbol of freedom in the 90s and 2000s. Isn’t this a bit of a paradoxical situation?

HWK: In the ’90s/2000s, it was a hacker culture: “We’re gonna put that Chomsky video up there and the whole world is going to change now.” And then we realised that wasn’t gonna happen. After about 10 years, the Internet is full of people selling stuff or white supremacist stuff or whatever. Those are the things the Internet does a really good job at promoting. There are an extractive element to the Internet, [seen in] platforms. These companies, for-profit companies; they don’t have a public surface imperative, and of course, they don’t care about you as a writer or a content provider. You’re perfectly good as long as they can extract value from you, the minute you aren’t valuable, you’re just another one on the pile. In their eyes, everyone is replaceable. Suddenly there’s a political dimension. Certain kinds of speech get censored, for example, comments in favour of Palestine’s independence. It gets censored immediately by Facebook. Social media are highly political entities, and they pretend they aren’t. That is, obviously, a bit fatuous. With regard to the print stuff, I think it’s coming back, weirdly, but the problem is always in ownership. You only have as much freedom as you have ownership of a press. But nobody can stop you from printing pamphlets at a coffee shop somewhere.

OT: Talking about dismantling the digital media ethos, the physicality of digital media became a big topic in the past years. From the excavation of precious metals and intentionally destabilising countries of the global south to the ecological impact of huge data centres, the original idea of the dematerialised medium has started to crack.

HWK: There’s a lot of artists doing work around this from Tabita Razaire, to Metahaven, to Yuri Pattison, to Anna Witt, materialising supposedly dematerialised space. As you say, extraction of minerals from places like DRC, dumping e-waste in Ghana, and digital labour abuse in the global south via pennies-per-hour click and comment farms. To make it personal, I was working for this company called Blouin Artinfo who, briefly, published Modern Painters and other once-respected titles, and at one point they had an office in India where they didn’t pay anybody eve. They were doing CSS, web design — very highly skilled workers — ripping off dozens of people in desperate situations, and it hardly needs stating that they didn’t pay their freelancers either. There are numerous legal cases against them, not least by me — which I won, and they still haven’t paid — but this is a business model for some people, and the online media culture has produced and reinforced this dynamic of full spectrum extraction. You effectively steal the minerals, and the labour to produce them — through contracts with corrupt officials and through wage arbitrage (often in countries that were once colonised) You hire someone only after they’ve done outsourced brand building for free via social media, then you steal the labour of your pseudo-employees via abusive freelance contracts. This is not just BAI, this is a lot of companies. You create ambiguous labour spaces like ‘internships’ which allow you to exploit labour for free, and in extreme cases like Blouin Artinfo, you don’t even pay contracted workers, and you don’t pay them when they defeat you in court! It is the Trump model, and tragically he was ahead of his time. The nature of capital labour relations in the media are infused with that kind of extractionist mentality from beginning to end. Feudalism is almost a euphemism for this kind of business model.**