Berlin’s TLTRPreß has released the latest issue of The Yap, first printed in March, with an excerpted interview from the zine re-published on AQNB today.

Led by Ondřej Teplý, The Yap’s 77th edition addresses printed media in the digital age, musing, “can publishing projects also experience a mid-life crisis?” Focussing on the subject of independent presses from the perspectives of a writer, book designer, and a performance artist, the project features interviews with Habib William Kherbek, Monika Janulvičiūtė, and Ivan Cheng, who discuss their recents projects and experiences working with publishing houses such as TLTRPreß.

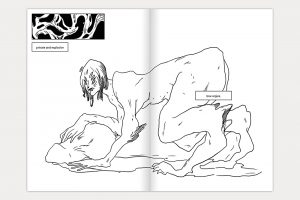

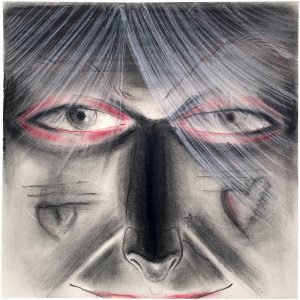

In the first interview with Ivan Cheng, up today on AQNB, the Amsterdam-based artist, writer and performer discusses gay vampires, club culture and his TLTRPreß book Confidences/Baseline. The novel—being the first of his Confidences series—deals with topics of desires, sensuality, and the needs of immortal beings, through diverse storytelling methods. Invested in notions of the public and accessibility, he produces films, objects, paintings, and publications, addressing performance as a critical medium to stage complex and precarious spectacles. Cheng has exhibited at spaces including Édouard Montassut, Paris, Centrale Fies, Dro, and Maxxi Museum, Rome. Confidences/Majority, the second in his vampire series, was published in 2022 by After 8 Books, and he initiated the project space bologna.cc in 2017.**

Read the excerpted interview below and see TLTRPreß for more information.

—

Ondřej Teplý: Your newest book, Confidences/Baseline, “plays with the vampire novel like a dollhouse. Characters who variously believe in the power of theater and performance become entangled with grief, desire, and the unknown.” For me, the gay vampires in your book define our time so well. We live in an era that is seeing the gradual dismantling of gender roles as well as a constant fear of impending doom. Gay vampires not only combine both of these characteristics, above all, they’re eternal beings, and because of their nature, they can’t fit into any hierarchical structure.

Ivan Cheng: There’s a strong psychoanalytic tradition to the role of vampires in the cultural imaginary, not least as a sexualised outsider. I’m interested in your reading of my story as not fitting into hierarchical structures since I thought I was placing the characters in sites that have very clear hierarchies: Jabberz, a historic gay bar, and the Wagon Wheel, a roaming theatre with the mind to find new audiences. But you’re right, they have ambivalent relationships to these dominions which they also initiate. Do you think of them as preservationists?

OT: Kind of. On the one hand, they preserve the status quo, but on the other hand, they’re anti-system because of their eternal lives. How did you come up with these characters?

IC: Hmm, I’m delighted that you think of them as characters, because there are moments where I doubt their substance. I told myself that they should read like a script’s character, void enough of characteristic markers that the reader would fill in their image. I’m remembering that I was trying to passively skirt the conventions of the novel, where you’d identify protagonists, their foils, and complications. They don’t play against much, except when they propose sincere actions, and [they] are a little extreme. The reader doesn’t meet too many vampires in the book, and their specific rules are also only sketched out, but I was drawing a lot from Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, the homoeroticism, notoriety, and non-copyright of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and reproductive technologies vibe of Dodie Bellamy’s Letters of Mina Harker.

OT: Another topic which is strongly present in the book is that of cycles and constant repetition. Sometimes it even felt like time and space lost their meaning and everything became one indistinguishable mass. Did you write the book from the perspective of vampires because time, and therefore space, aren’t a measurement of their lives?

IC: I guess I was more interested in the breaking of a traditional timeline than speculative vampire mode. Each chapter exists quite conventionally on my plotting board as being a moment in time between 1994 and 2019. That’s a timeline that continues to upload in my next book of the series. Maybe it’s important to note that Confidences/Baseline is intended as the first of a series which currently has no endpoint. The series proposes to be about nightclubs as spaces on the private side of the public. “Nightclubs” as a loose term in relation to the vampire and their haunts, but a broader, notionally subcultural metaphor, of which there’s never really a full understanding. The way the chapters are presented doesn’t prescribe space and times; rather, they’re sketched out with light descriptors through the body of the text. So while it’s a matter of closeness in reading, you’re right in that there’s very little interest in elocuting clear difference.

OT: The inaccessibility of nightclubs links the whole series. What do you find so fascinating about nightclubs? And what, in your opinion, is their social role in society?

IC: I’m not a club person. I’m not running or owning a club. I don’t sell drugs, and I don’t DJ. It’s not my system. I’m very happy to be there as a fan or friend. I’m rarely there for escapism, or to lose myself in time; clubs don’t occupy that space in my imaginary. But we can begin on a simple level with door policies which mean to protect certain communities who find their safe haven there. In my lifetime, subculture has become less culturally murky. I was reading a recent novel that cited Berghain as a destination, and I thought immediately about Claire Danes on Ellen Degeneres’ show talking about the club: the exclusivity that it has come to represent for so many people.

To riff in this cringe vein, when people during the last two years have been talking about missing clubbing and wanting to go clubbing again that’s also referring to a kind of assumed, shared experience of pleasure. I’m thinking about institutional spaces and their way of dealing with difference. There’s the question mark of what spaces should be open, what should be closed, and the soft infrastructure for making spaces accessible. Is experimental writing a gateway towards the intonation of performance, or vice versa? Becoming a vampire might be cute, but what could it mean in terms of being in, or out, of society, and what are the fathomable consequences? My book is far from controversial, maybe irritatingly entertaining, and it’s not taking a position on inclusivity as a bad policy.

OT: People know you mainly as a performer. The book is also heavily influenced by performative art, especially the way it’s communicating with the readers. How do you combine such different types of media?

IC: I approached writing this book with a similar attitude to writing [a] performance. The timeline was short; it was specific to a context, and it began with a sense of the structure I wanted to have. What feels different is the greater trust I have in an audience being able to interpret some meaning. In performance, I sense that synthesising the meaning of the text is not the primary concern for the viewer.

I’m aware that writing a novel is considered a craft, but I also have a deep affection for the amateur, or dilettante, energy from things like NaNoWriMo, where people write a novel in a month, or the realm of fan fiction, where existing characters are recast in scenarios or transplanted to complex alternate universes. These questions about reading and receiving, and what people take away, or what people want from a cultural product, are a motor of my work.**