“We hung out, practiced Pillowese, hosted a failed dinner for a party of 25, and spoke about making a conceptual harp album and rigging the apartment with microphones, making music videos at the Olympic pool where Kylie Minogue’s iconic ‘Can’t Get You Out Of My Head’ was shot,” writes Barcelona-based artist Lydia Ourahmane via email about the fun and organic process behind an ongoing collaboration with producer felicita in London. The two artists had been working together on developing their own language, called Pillowese, which was conceived during an artist residency in Italy’s northwest in April. It’s a glottal and often-aspirated construction, borrowing from English grammar and resembling a cross between Finnish and Romanised Arabic when written down. It debuted as part of Hong Kong project trust & confusion‘s ‘Voices’ series in July, where peers Xiuching Tsay, Steph Hartop and felice bauer were recorded reciting and lending their own accents to this unique new tongue.

Fast-forward several months since that fated encounter-come-collaboration, and felicita will be live remixing the soundtrack to Ourahmane’s Survival in the afterlife solo exhibition for the Museumnacht 2021: Notice the direction of fires event at Amsterdam’s de Appel on November 6. It’s a show based around an active spiritual movement the Ourahmane’s family founded during the Algerian Civil War, called The House of Hope, and one that focuses on the kind of community and world building that is central to her practice. “I invited Yawning Portal to come back and spend a week with me writing and making the sound piece,” Ourahmane writes, about birthing the electronic composition after meeting up with one half of the Chicago and London-based duo in Barcelona. “I think something glitched in my head after I listened to one of their tracks, ‘The Burning Bridge’, on repeat for two days, and called Jess right away in a sort of frenzy. Their music feels familiar to me in a way I can’t pin, and I think felicita shares the same world. The generational qualities of growing up on the same music enters you into a conscious stream.”

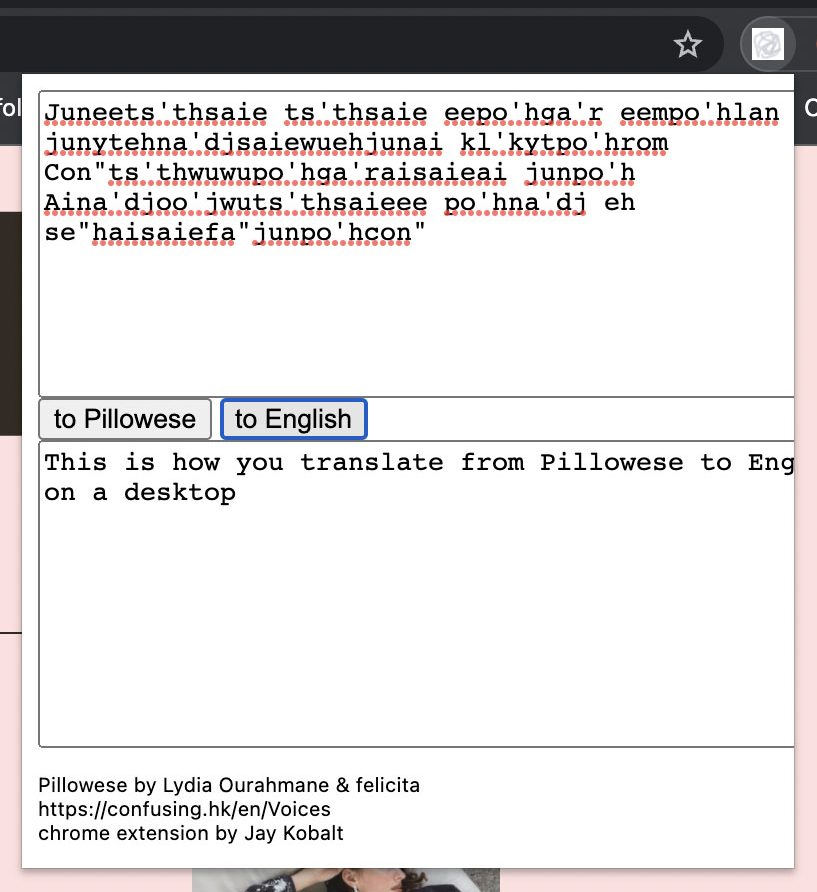

With that, Ourahmane and felicita drop their downloadable Pillowese Translator app, created by Jay Kóbalt, via AQNB today. It’s a browser extension that you can upload to Chrome via Preferences > Extensions and selecting [Load unpacked]. Read on for more insight on the project and see here for its Pillowese translation.

**Can you tell me something about the Pillowese project and what inspired it?

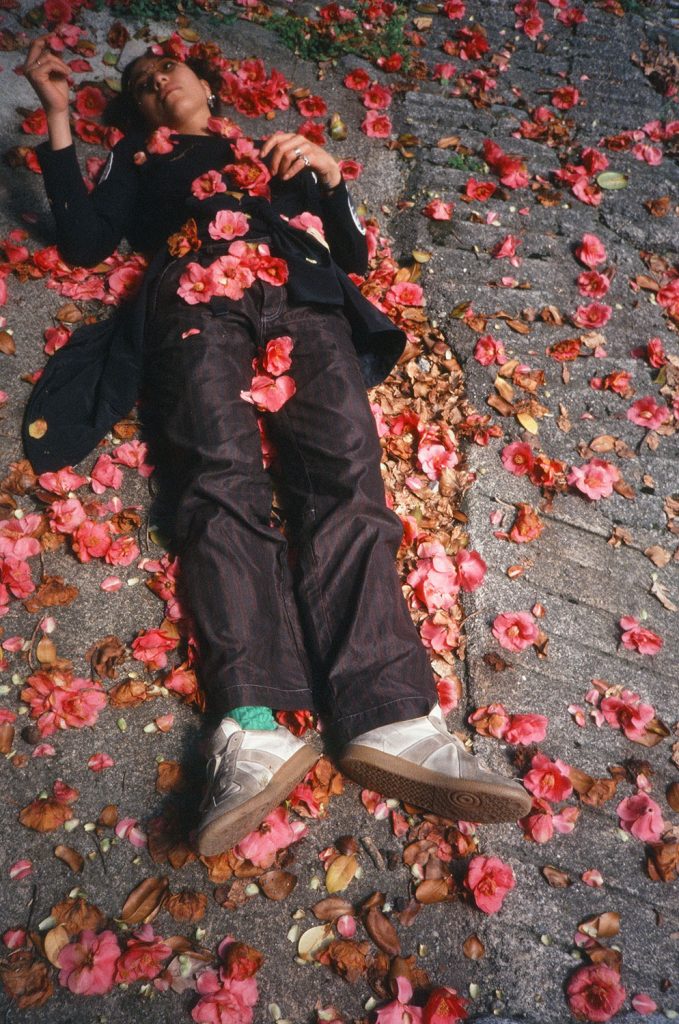

Lydia Ourahmane & felicita: At the Lake Como Malevich Residency in April, we spent time listening to recordings of glossolalia (speaking in tongues), and discussed the languages created by individuals (and very rarely shared) to communicate directly with God, or to express spiritual insight or messages. We hadn’t seen each other in a long time and ended up sharing a room, where we would lie in our respective single beds talking in and out of consciousness while we fell asleep. We joked about pillow talk, which soon birthed ‘pillowese’. It is a kind of liminal state between consciousness where you’re spilling without thinking, so the air in the room becomes this bleed space for dreams.

**You had some people interpret the text into spoken language for the trust & confusion project, what are your thoughts on the impact of accent on pillowese?

LO & f: It’s rare for a person to speak a shared language ‘fluently’ for the first time, without any guide or instruction. This gave a lot of space for the unconscious mind to act upon the sounds. Sometimes embedded accents acted as a mask, other times the mind would search for a voice, and land somewhere mysterious or unexpected. One native English speaker developed a Pillowese accent, which sounded faintly Celtic. It’s diction also encompasses an aspirational quality. When we were thinking about the sounds of the alphabet, we maybe subconsciously created an amalgamation of sounds from various languages we already knew, and/or sounds that sat into our mouths well whilst unlocking midpoints between these rehearsed structures creating a sort of phonetic dissonance. This collision of sounds the mouth was not used to producing affected the potential for the speed of articulation in spoken form, but there is an overarching fact that the learning of new languages always begins slowly. The mouth has to make more room, so it’s also about discovering that negative space.

**Presumably it would be difficult to create a language but you did this relatively quickly, how did things like phonetics and phonology play into how you developed it?

felicita: I remember us exchanging possible alphabets. Then one day, very early in the morning, Lydia sent me the entire alphabet, fully formed, with the pronunciations in a voice note. I quickly applied a grammar and we started sending each other messages in Pillowese at different points of the day. The sounds themselves were conceived texturally, where each form interrogated different parts of the mouth. I thought about it more as a lingual exercise, and borrowed sounds I imagined to be sensually stimulating—tongue rolls, multiple consonants, friction. Language creates a desired space, where sounds themselves are reputable in how they affect its use.

**Did you apply English grammar and lexicon to the structuring of the language itself?

LO & f: We borrowed the English grammatical structure as it was the simplest way to teach the language to everyone. Taken out of their cultural containers, grammatical systems start to look like abstract code. Why does Polish have so many complicated cases, and why does Chinese at first appear to have no tenses, yet is tonal? The potential to inject spiritual energy into codified sounds is where it gets really exciting, and takes us back to our original interest in glossolalia.

**With that in mind, given that each reciter of the language adds their own distinct accent to the pronunciation, do you think it would have developed quite quickly into its own dialect of sorts?

LO & f: It would be interesting to speculate how it might organically shift, and how quickly. An early idea was to invite people from different linguistic backgrounds to create new words or slang in Pillowese, and then to feed these creations back into the language. Pillowese could then become a living language, mutating organically, and potentially be adopted for any purpose—as a cryptolect, for example. The Pillowese translator app is just the first step.

**I get a sense of this interactivity and this compound mutual osmosis of sorts, in the exhibition—felicita’s remixes of the Yawning Portal sonic environment, this reference to pillows… I’m curious to know what your thoughts and intentions are in that respect. Particularly in relation to this world building regarding this secret House of Hope commune.

LO & f: I’ve always worked very collaboratively, thinking with and through the people I am surrounded by, and so this sort of world building comes naturally, I think, as a way of living I am well versed in. Community is primarily about sharing resources, it is about recognising your part as crucial in the evolution of play, which we dress up as work in our current phenomenology. The House of Hope was a place of refuge for many people, some of whom were escaping very difficult situations, and some of whom were there to cultivate a new way of living, which was quite radical at the time. It inferred a dedication in the divine sense, where the potential of persecution was masked by the potential for a sort of spiritual transcendence. I was always in awe of this, that the body can become secondary in a lived experience because the focus was elsewhere. I think actively making a position to take in this world is always met with friction, because you are essentially forcing more room to exist around this new form you have brought into orbit that can be ideological, physical, material, visual, sonic etcetera. They move freely across all tenses, the same way a recent discovery might shine a light on how we read history, which becomes filtered through the future’s lens. World building is a grasp at eternity, the pillows were an allegory for burying time.**

You can download the two artist’s Pillowese Translator here.