“I think it was the first time I thought about stringing things that could seem difficult and disparate together,” writes Gian Manik about how it was Aphex Twin’s 2001 album drukQs—that he heard as a teen in Perth, Western Australia—which influenced his approach to his practice. “I like how any genre could make a mix. It seemed to make more sense for me than having to curate one or two styles together.” Now based in Melbourne, the artist is the latest to contribute to AQNB’s art and music compendium series, providing the cover art (along with graphic design by Alex Deranian) for this 2 tired 2 cry edition, based around a theme of collective difficulty and setbacks in 2020.

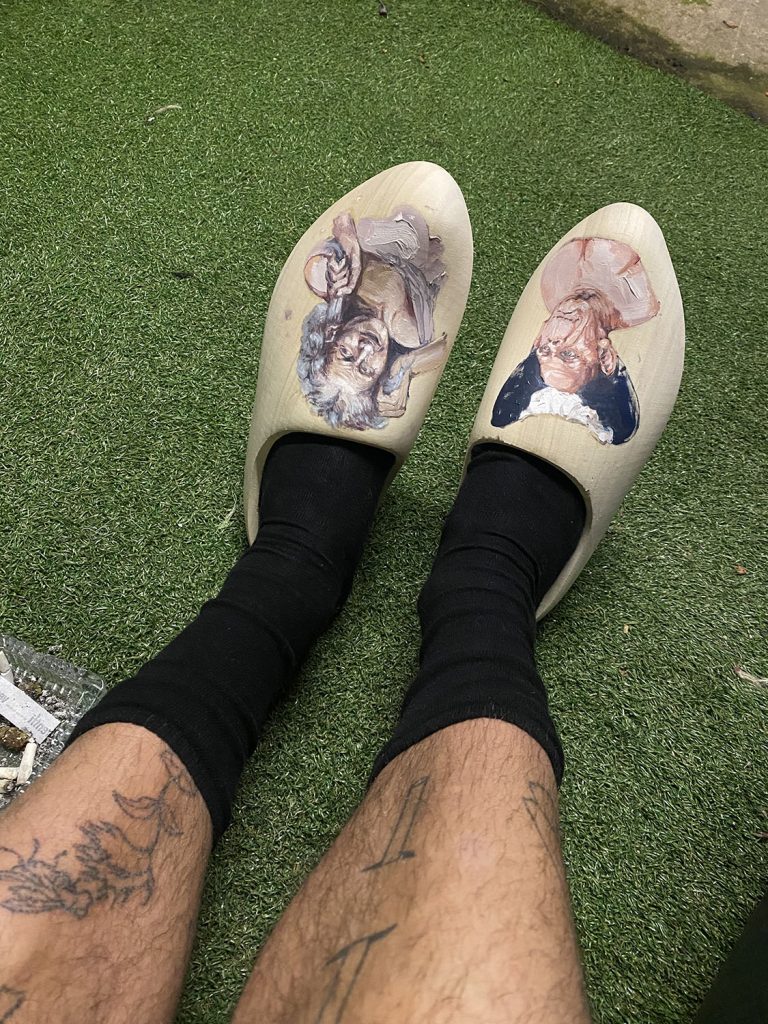

Working across disciplines and media, while focussed on his extraordinary talent as a painter, Manik was raised and educated in an old-school tradition before undergoing a period of revolt against technical proficiency in art school. He moved into sculpture—inspired by actor-less horror film scenes, his band called Mass Birth—all while developing an eye and ear for contrastive pastiche in his exhibitions and mixes, fashion sense and personal tattoo collection. This bold, often chaotic approach to creative expression is something Manik himself refers to as ‘curated filth’, where a community-oriented mural project winds up on a wine bottle label, or impeccable reproductions of Rembrandt paintings land on a knife, a pair of clogs. “I’m not too precious about that kind of thing but these were re-used for friends’ projects. Other than that, I wouldn’t really spread a work so thin, unless I got fuck loads of money,” writes Manik—in his typically irreverent manner—about the repurposing of existing artworks into new forms. “I do like the idea of work disbanding or becoming confused, from a gallery wall to a repeat print, to a wine label, business card, etcetera.”

It’s in this space of embracing diverse cultural and aesthetic references that Manik’s work thrives. A recent exhibition at his representative Sutton Gallery included images of a drug bust in ‘NSW Police Find $200 Million of Meth Hidden Inside Sriracha Bottles’, a depiction of an impossible gay sex scene in ‘Long Session Fucking and Getting Fucked by Myself’. Meanwhile, an upcoming collaboration with Melbourne-based fashion label VERNER—called Joint Venture—features repeat prints of 40-plus of his paintings.

It’s with this in mind that AQNB corresponded with Manik about his bold and irrepressible approach to painting and artistic production.

**You’ve been making a lot during lockdown, how long does is take you to do a painting on average?

Gian Manik: Hmm, not very long. I’ve been painting for ages, so I don’t tend to labour or fix things. Plus, I have the shortest attention span, which means I try to finish a work a day. That was the type of thing that I was doing during lockdown though. It regulated my practice, anxiety and schedule. When we went into the second, hard lockdown, I was like, ‘FML, I can’t have all this shit around’. I also hate having things rolled up or lying around, so I tried to work on one or two larger works by collaging smaller paintings I could finish quickly, over the top of each other. I used to do things in layers previously, so I would work on several paintings at once and they would take a lot longer because, oils etcetera.

**I’m interested in how you became an artist, you obviously have a lot of talent technically, and your ideas are very specific, was it always clear that’s where you’d end up?

GM: Kind of. Cue violin: My grandfather was a painter. He immigrated from Holland with my nana ages ago. He only painted clowns (LOL). Our house was full of fucking clowns, all the kids from school hated it. Mum also painted when she was younger—mostly reproductions of Rembrandt paintings.

I was sent to art classes when I was five [years old] and had a portrait painting mentor when I was 14 that I saw for years. It was pretty cliche. He would tap my hand when I made a mistake, I loved it. I thought I was in Stealing Beauty or something. So, I had all these old-school tools and sensibilities when painting before I went to art school, it was hard to dismantle. I always struggled with politics and concepts around work, coming from such traditional schooling.

**Your work seems to operate so much with juxtaposition and a kind of ‘found object’ approach to your compositions—even if they’re painted representations of the thing, it’s as if you picked them up and placed them there. Are these conscious decisions you make, or are these choices more intuitive than that?

GM: Yeah right, umm. I said before that I found it quite a long process, coming from pretty much painting portraits of lawyers and judges for money when I was a teenager. I had an agent, LOL. Art school and this particular class, interdisciplinary drawing, helped with using concept as agency, and then representation, or a lack of, would follow. I created this specific way of validating representation by manufacturing abstract imagery, or foils and mirrored fabrics, that satisfied re-presenting verbatim. I was able to work from images that seemed a lot more of the work that I wanted to do—I guess, probably, Abstract Expressionism.

Working from this past, I began, perhaps a few years ago, using more recognisable subjects, everyday things; stuff that I took pics of; internet trawling to display concepts or ideas for exhibition. I think the work shifted from works that unpacked analysis (self-mirrors ‘blah, blah’) to a more therapeutic expulsion of imagery through concept. It was immediate and confusing, especially when trying to manipulate technique and style that wasn’t so linear.

**As we mentioned in your recent, second mix contribution to AQNB—‘Knock on the Door‘—your approach to music is similarly surreal; this kind of contrastive sonic pastiche of disparate cultural and aesthetic references. Would you agree and do you see a link, or even, is it all part of the same practice?

GM: Yeah, I’d say so! I think I dress the same too :/ I called it ‘curated filth’ to a coffee shop guy the other day.

**I’m interested in the title for this work you did in the Pilbara, ‘What’s your name. It’s a symbol. Don’t talk.’. I think this is something that comes up when talking about your ideas—where you would focus on a certain ambiguity of meaning in opposition to giving a clear explanation, does this title allude to this kind of evasiveness at all?

GM: Sort of. I was in the desert for a month and I feel like titling work can be easy, or if it’s hard then it’s usually ‘Untitled’, aha ha. The work was a conversation of sorts between the residency program, gallery, curator, and contributing teenagers from the local school. I was keen for them to do whatever they wanted, like when people doodle on their desk or something. I used ‘landscape’ as a locus to calm their supervisor but said that anything is landscape and graffiti is too.

The title came from me watching an episode of Law and Order SVU while I was up there. When I finished painting for the day, I would get a big beer and watch SVU. I’m pretty sure in an episode one cop was like, ‘what’s your name?’ Then I walked out of the room and heard someone else say, ‘it’s a symbol’. Then after a bit I heard, ‘don’t talk’. It was cool, like a conversation that no one was really helping respond to or able to understand, which is how I saw the work function in its synthesis.

**In your description of that work, you talked about refusing an impulse towards relational aesthetics, and focusing more on just aesthetics—whether that be, the stylisation of an element of the painting, or the way the canvas was folded—can you tell me something about this approach to this project, but also your work in general?

GM: I think having the work be ‘collaborative’ was weird for me. I really don’t like collaboration in my painting practice, which is funny as I do it in other projects. I think that having the kids work on areas in their own ways (imagine the Stussy ’S’ but lots of them) didn’t really allow me to control style or any particular aesthetic. In a way, that was a particular departure for me to use recognisable and realistic subjects from then on, rather than have to fold to nuances and laboured abstraction in order to make something interesting.

**What happened to that mural in the end? I know part of it ended up on a wine bottle, but you’re also so hyper-productive that a lot of it ends up given away or in the trash. Did this one meet the same fate?

GM: LOL. That thing did the rounds. I was so sick of it that I cut it up into 10 pieces and a bunch of friends from all over the world bought pieces of it. I hope I never see it again. If I ever have a ‘your’e about to die’ show, I hope they can never find any of the pieces. I love that work, but it’s done its thing. I did another painting similar to this and it became covered in mould from being in my studio on the floor. I was so happy taking it to the bin 🙂

**You also used to work a lot with sculpture, and some video, then you had a period where you returned almost exclusively to painting, but tactility and form was still so central. Would you still call the work sculpture?

GM: I think so. Essentially, all those other mediums I was playing around with were process for painting. I would usually have to validate that process by executing painting, so I thought that that became superfluous, also time-consuming. Like having a photograph and then the image of it re-presented, hung side-by-side, that material exploration can happen behind the scenes. I think now, with more recognisable subjects, the circuit is shorter. If I were to use other media in the future it would probably be confusing the paintings. Then that just falls into post-internet consolidation, which I don’t think I’m particularly interested in. **

AQNB’s 2 tired 2 cry music & art compendium is out today on November 24, 2020.