“At the moment I’m more interested in being really thorough in how I go about gathering perspectives of the past,” says artist Ashley Holmes via email, about using archival footage in his video work. “Of course, I’m constantly thinking about the future, but to progress to that point it feels important to first have a strong relationship to the language of the things you want to exist within, and how they look and feel in the future.” We were chatting about how history plays into the Sheffield based artist’s practice, in the lead up to Les Urbaines festival, running December 7 to 9, where he’ll be exhibiting a new piece.

Working across installation, video and mixed media, Holmes’ interest in music culture — especially that of a Black British perspective — is what threads his diverse practice together. His current solo exhibition, called Cry Then Win Then Lose Reaction and running at Leicester’s Two Queens, draws on YouTube videos of Americans reacting to British hip hop artists. As these viewers start to develop an understanding of the UK “rhythm, tone of voice and the musical elements of what they are watching, the relationship and understanding between the viewer and performer move closer to one another.”

** What’s the relationship to music, or more specifically music cultures in your practice?

Ashley Holmes: Music both heavily informs and feels intrinsic to my practice at the moment. It’s definitely played an important role in widening my perspective and understanding of the cultures that surround a lot of the material that I’m interested in. The points of reference for the music I’m collecting and listening to right now span a number of genres, usually made from a Black British perspective — a starting point for a lot of the things I make and think about.

I guess I am most interested in rocksteady and lovers rock styles of reggae music, and in the origins of lovers rock. As a genre, I’m interested in it having heavy Jamaican influence, but being indigenous to Britain. A lot of the music was made by the children of the Caribbean communities who had arrived in the UK, so it feels important for me to keep returning to a place where I can deeply consider the social and political landscapes at this point of the mid-1970s. And with that in mind, I think about the entirely new set of experiences of a generation of young Black people who were about to encounter a reality which was full of racism and oppression. I’m interested in the collective cultures that surround music and the potential it has to document and provide a voice that speaks of the struggles, romances and heartbreaks both politically and socially. For me, lovers rock as a genre is my springboard and blueprint for everything that I’m thinking about around musical recordings and documentations of a Black British struggle.

** You host a radio show called Tough Matter on NTS Radio. I’m interested in this because your work seems to consider how the means of distribution can shape culture as much as the content. Radio has a history of being a democratised medium before the internet (like pirate radio, for example), is this history of broadcast media something you’re tapping into?

AH: Yeah, for sure. I grew up listening to lots of different music through mixtapes and radio broadcasts. I’m trying to consider the histories and importance of Black Radio the longer I am hosting shows. I’m feeling more comfortable in those kind of spaces, the more time I spend in them, mainly because I also feel myself developing a better understanding of the potential and importance of thinking about radio as a learning resource and a means of documentation. As well as having a platform to share music we are listening to, how can we begin to think about radio as an extension of the way we archive and document culturally significant questions and creative practices?

**In your current show at Two Queens in Leicester, you look at YouTube reaction videos from American YouTubers reacting to music by British hip hop artists of African and Caribbean heritage. What did these reaction videos say to you about the wider transatlantic cultural relationship? Do you think music is a useful lens to examine cultural identity more broadly?

AH: In thinking about my heritage, it is important to think firstly about locality and how I ended up where I am today. And so, it then also feels important to look to other places, not just across the Atlantic, but globally and think about all of the cultural relationships that currently exist.

In the context of British music of Black origin, at this point in 2018, I can’t help but notice the shift in attitudes around the negotiation of who and where artists are supposed to look to for validation. Over the past ten to 14 years (particularly in popular and experimental genres of music that are related to and hybrids of hip hop and Black performance) there has been a narrative centred around the idea of trying to ‘break mainstream America’ as a measure of success, but for what purpose? In looking for recognition in that way, what are the perimeters and peripheries that the artists then find themselves existing on the edge of as a result? For how long are they supposed to try and exist in precarity?

The idea of a quite rigid blueprint or formula that supposedly grants access to success feels redundant in a time where artists across multiple disciplines are recognising their own power and importance of autonomy in the process of making and sharing new material. This shift feels like it’s gathered speed really quickly in more recent years. I love it. The acknowledgement of it being an almost trivial exercise of searching for permission or validation from an audience that has such a differing position and perception of how they see themselves is a powerful position to be in. And so I’m fascinated with that butting of heads. The clash and the confrontation and everything that falls out of it. Who is looking at who? British artists no longer look to the US for recognition in a way they had done previously. I’m interested in the quick fire exchange in glances and movement in the direction of who is assuming the role of the audience and performer. In Cry Then Win Then Lose Reaction at Two Queens, the video installation tries to articulate and be constantly re-thinking that.

**I particularly like the works at Two Queens because I find reaction videos to be so interesting, a really public way to consume music. The way YouTubers will hold off listening to a track they want to hear so that they can stream their reaction; even people making reaction videos to reaction videos. How do you think social media has affected music culture, do you have any thoughts on that in relation to some of the works you’ve made?

AH: It feels difficult to think about music and social media not being intertwined with one another. Maybe it’s for the better and maybe for worse, I dunno. I do enjoy thinking about the relationship between the two, though. I’m often conflicted about what I think or feel about it if, I’m honest. I think that plays out a little in the work. I’m confused and then worried at the speed at which things can be recognised as culturally significant but I like how closely music cultures look to some of the more specific functions that differ between each social media platform as a means of support. So not just the album release but the video documentation of the live show, the podcast that talks about the beef, the Twitter thread that scrutinises the bad interview. I like that there is an element of reliance. I want to think about what happens in having that mobility and what it means to create new things within these platforms in a way that encourages more interaction, conversation.

**You work a lot with digital culture and found material, does this affect your decisions in how you put your own work online?

AH: Yeah, I guess that ties in to the answer above. A lot of the decisions in how I work with existing material looks back to cultures of sampling as homage, but also I try to document and consider differing perspectives and approaches to interactions in digital cultures. The retweet and share, and repost are good examples. Not to say they are the most important but, at the moment, I’m interested in the movement between original and found traces of material; what does being granted permission to re-present existing content allow?

** I just watched your video work ‘Forward’. How does history figure in your work, i.e. looking to the past in order to get perspective on the future, or a sense of continuation?

AH: In a similar way to what I mentioned about radio broadcasts, ‘Forward’ is another means of thinking about archiving, but just from a different viewpoint. So, if radio can document recordings of sound, instrument and voice as a signifier of a particular period of time, what would the equivalent of that, in the context of visual and screen-based cultures, feel like? A series of still images taken from internet searches and edited screen-grabs flash on screen at a high speed, giving a snapshot into documentation of events and material that facilitated and created space for collective activity from the lovers rock period of the mid-1970s up to the modern day.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=imjse3lW224

** In light of some of these thoughts, can you tell us a bit about the work you will be showing at Les Urbaines?

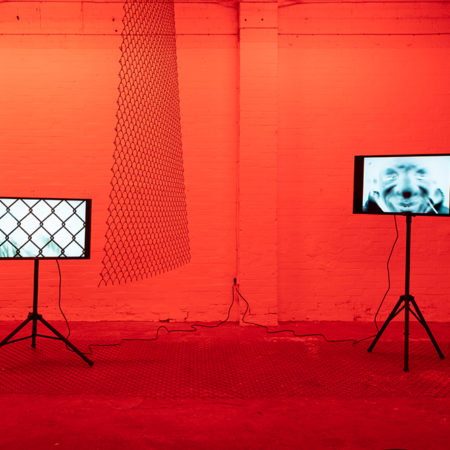

AH: The work is called ‘Routine Check’ and is a newly-made installation that comes from several conversations and research over the course of 2018, based around an interest in processes of recording and monitoring. How do we take care of the things that we deem as valuable, and when that is at threat, what are our defence mechanisms and relationship with protection?

The work is a presentation of sculptural and moving image-based works across the three floors of exhibition space. It explores the nuances, aesthetics and processes of archiving live performance. I’m interested in ways of recording the voices, possibilities, impossibilities and agency within the infrastructures of contemporary creative practices. So, I’m really excited to be sharing this new work in the context of a group exhibition pulled together by wonderful curators like Deborah Joyce Holman, who have an incredible sensibility of the language and conversations that contemporary creative practitioners sit in relation to one another.**