“I had a phone that literally didn’t work. I was like, ‘Oh, I could buy a phone that works, for the first time in years’. So that was a pro,” says Swedish producer Julia Svensson wryly, about the reality of being an artist in one of the most expensive cities in the world. “I’m not making bank. I’m not becoming rich from my full time job. But I have a steady income and a bit of extra money. It takes up a lot of your time. And, especially now that I have gigs and stuff, it’s constantly building on top of it.”

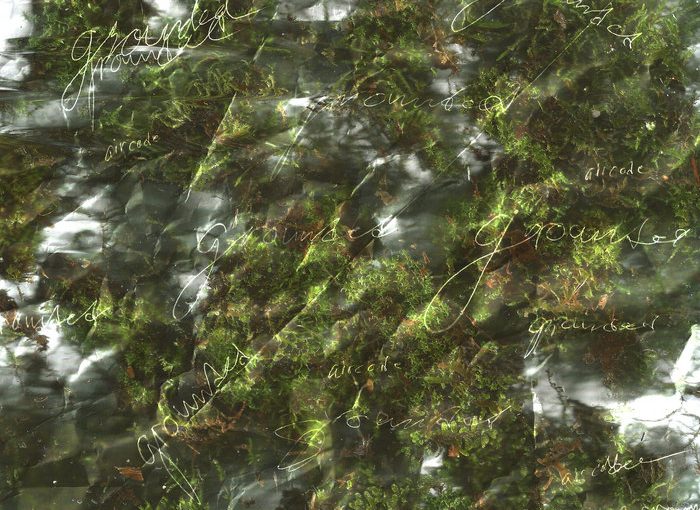

Moving to London seven years ago, Svensson has gone from studying sociology and struggling as a student to being overworked, if marginally better off, while trying to balance a day job with a burgeoning career in music. Her debut album—called Grounded and released via Chloe Frieda’s Alien Jams label in January under the Aircode moniker—swells with a torpid and textured low-end that filters through fragments of piano, voice and guitar. A chaotic sonic ferment with hazy echoes of dub, trip hop, industrial, the download and limited-run CD follows 2020’s Effortless—dropped in the thick of pandemic lockdown and bringing with it the somnolent anxiety of waiting in isolation.

Grounded builds on this sense of stillness and stuck-ness by expressing a desire for escape into nature from the ruthless daily grind of London’s oppressive urbanisation with a loop-laden and layered dark ambient. Here, the black mould and damp of Svensson’s adopted metropolis is transmuted into the dreamy fresh air and woodland moss of home.

**I’ve been reading this self-help book that talks about how humans have a dissociative attachment to the earth, and that, on top of that, we’re all dealing with a major depressive episode because of the current precarity of the environment. This might be a bit of a leap, but I’m getting this sense from your music.

Julia Svensson: Yeah [laughs]. In terms of this last album, it draws a lot from moss. When I say moss, it’s mainly the atmosphere of what I imagine being inside moss would feel like. I think there’s a lot of correlation with living in the UK—the dampness and the cold.

I grew up around forests and stuff like that in Sweden. I would go to the woodlands and just lie down on the moss because it was comfortable. Then you come here and it has that kind of atmosphere, which is comforting in some way. It’s obviously grey, and humid and everything but if I just think about it through that aspect, it kind of helps with being in the UK. I tend to go to nature a lot. I live close to the marshes, and Epping Forrest is kind of close. Just being in an office, being locked in a box, it is like being dissociated from nature. Like, ‘oh, it’s out there somewhere’.

**There’s a lot of focus on texture in your music, what is the relationship between nature, texture and tactility in your work?

JS: I create very intuitively. I don’t have a plan at all. It just grows out of nothing and then becomes whatever it becomes. That’s kind of the way I think of nature. I like to think it’s there. There’s a lack of effort, based on so much effort. For me, personally, the most comes out of when I’m not trying at all, it just happens.

Obviously with all the sound I use, I’m not out there doing field recordings and stuff so it’s very loose. It’s not the direct link with nature, it’s more the process of creating. You can view it in so many ways, but that’s how see it. It’s this growing out of whatever it is and it just becomes something.

**That reminds me of a meme I saw referring to a person getting an arpeggiator, refusing to read the instructions and just figuring it out.

JS: Yeah, I’ve learned music by just randomly pressing stuff until I like the way it sounds. It’s a very tedious process, and it’s also partly this weird laziness. I was like, ‘should I look up a YouTube video and learn how to do this, or should I just sit here for four hours and just randomly press things? Then eventually I guess I’ll figure out what this thing does.’

I don’t use arpeggiators or anything like that, really. I put literally every hit, or every thing in, very specifically. It’s loop-based, so I’ll make a section and then loop that a bit but I never press a button and have it do whatever it does. It’s still me putting everything in there actively, but it’s not planned.

**By ‘weird laziness’, do you mean bad focus, here you can’t imagine having the organizational skills to actually do it properly so you’re just going to wing it?

JS: I don’t know, I used to think, ‘Oh, God, I’m being so lazy and bad’ but it worked. It’s like that with a lot of stuff, where you try to be a certain way: ‘I’m gonna be super-organized. I’m gonna do this and this’, and as soon as you just accept it, you realize you’re like, ‘alright, sure, I can adjust certain things but this obviously works’ and you kind of stick with that. I still view it as just being lazy but it still led to good things that might not have happened.

**To me, having a clear idea of what you want a work to be before you make it is not how the creative process works because it assumes that there’s a finished thing that’s ready to come out, but it’s also the process that influences how its realised.

JS: Yeah, exactly. I think I everyone’s different—whether you like planning and organisation, or if you’re intuitive and lazy. I’m gonna stop calling it ‘lazy’ because I don’t think it’s actually being lazy, but it feels more fun to bully yourself [laughs].

**I’ve been thinking about temporality in terms of music and the technical side of it. I made a cassette tape mix recently for a friend, and a thing that I realised is the durational nature of waiting for music to record in realtime, rather than just dropping an mp3 file into a folder. It changes your experience of and relationship to music.

JS: I think that’s kind of why I also wanted to do a CD. I don’t care about vinyl. To be honest, I don’t have a vinyl player, they’re really expensive. I don’t know how to play a vinyl. I’ve never put a vinyl on. I don’t have a personal relationship to vinyl. With CDs, I love CDs because it’s still got the same concept that you can look at it. It forces you to engage with it in a different way. I’m sure whoever bought my CDs was literally like, ‘Ah, cool’; and put it aside because no one has a CD player. I do. But in terms of a physical thing, it forces the creation of something more substantial.

**When did you start making music?

JS: When I was 19 [years old], in 2014 maybe. I lived by myself in Gothenburg because I did a university course and didn’t have many friends there. I also didn’t have anything to do because my university course was two hours a week or something. I had a lot of spare time and a lot of procrastination from studying. So I just started making music in Logic because it was the only thing I could do. Then I kind of developed and started making pop stuff because I thought I wanted to make pop music. Then that changed quickly. And then I accidentally made loads of witch house. It just escalated. I didn’t do anything properly, or put something out; or feel I got to where I liked the stuff I made until 2018 the earliest.

**Did you think that you wanted to be a musician when you were studying sociology? What did you think you were going to do?

JS: Actually, I started studying psychology. After five weeks, I was I like, ‘I don’t want to learn biology, because it’s basically biology, and a lot of maths. And then I was like, ‘I’ll do sociology because I care about politics’, and then, ‘what am I gonna do with this? I could have read all these books in my spare time instead. I didn’t need to go to uni for this.’ I make a lot of stupid choices. I also change my mind a million times about everything.

**So music is the one thing that stuck.

JS: Yeah, basically, in different forms and shapes. But lately, in a way more consistent shape.

**Do you think that sociology has influenced your approach at all, thematically perhaps?

JS: I honestly don’t know. It’s something that’s affected my life a lot, how I view things because obviously if you spend that much time with something, which is also alongside other political struggles. Obviously, it’s taught me a lot of stuff but I don’t think directly—apart from mentally it impacted my view of things. I’m sure it played into [music] in some way, but I can’t put my finger on how.

**What about the anti-capitalist Sylvia Federici reference in ‘tunnel vision‘?

JS: Oh, yeah. I think it was because I was reading her and I just thought it was interesting. Obviously, it’s impacting my life and way of viewing things but I think, creatively, it’s subconscious. So it’s really hard to put a finger on how that played into it. I think more visual influences and stuff that is a lot easier. I don’t want to politicise my music in that way. I know a random Federici quote defeats that point [laughs], but I’m not trying to politicise my music, because I don’t know what I would say with it.

**Thinking in terms of the complexity of the cultural economy, environmental ecology, do you think that sense of nuance feeds into your approach structurally or formally in the music?

JS: I think in some ways I just have a refusal to… I kind of like the lazy approach, not lazy but it kind of refuses to do it properly. Even if it’s just internally, it’s like ‘oh, I just do this because I want to’. I don’t want to get stuck in the structure of ‘you have to produce this output’. I feel so much stuff is produced all the time and I’m obviously part of that, there’s so much output all the time. And at least for myself, I’m like, ‘I don’t want that output’.

**Like an anti-productivity?

JS: Yeah, exactly. In a weird way, I’m really productive in the anti-productivity, but at least I’m productive because I want to be. If I didn’t want to make music, I just wouldn’t. I don’t think my role economically is that significant but it’s at least this attitude of ‘I just make it because I want to’. I’m not making it because now I’m stuck here, and I have to produce new content and I have to release this because otherwise I’m not going to be validated. The culture, especially in London, is of constantly having to prove yourself that you’re actively doing stuff, which is so exhausting. I’m trying at least to not fall into that.

**There aren’t so many stylistic or genre references your music. It’s very eclectic from record to record, and within the track listings themselves. Do you have any explicit influences or inspiration?

JS: I just found out about the genre ‘illbient’. I remember when I had my first EP coming out, and I had a meeting and they were like ‘it’s kind of dub-y’, and I was like, ‘what?’ I just came from Sweden, you know? I listened to pop before. I didn’t know any genre. It’s got the heaviness of dub to some extent, but slow. I got really into 90s and 2000s illbient. It’s very downbeat, but also I like the snare sounds in there. It’s so hard to pinpoint that in the same way in the music, every track and stuff sounds different. It has a coherent mood, and atmosphere, and style but I even struggle to pinpoint where it comes from. My mind is too chaotic.

I listen to a lot of drum n bass, older drum n bass. I like he spacious patterns and things. Obviously, I don’t make drum n bass but it’s like, dub. My main inspiration was the soundtrack for the video game Time Splitters 2 [laughs].

**I’m kind of losing touch with music. Finally.

JS: Yeah, that’s good. You should. I’m joking. There are different ways of being involved in music. I’m involved in music in that I like listen to it, when I like to listen to it. Hanging out on Twitter is the last thing on my mind. I never want to read a thread about Techno Twitter ever again.

**I like thinking about memory and time in music. No one has a memory and everything has been devalued to such a degree because there’s just so much inflation, in a way.

JS: Yeah, it’s this weird paradise. It’s great that everyone makes great music and gets to put it out there. Then as a listener, you’re just like, ‘I don’t know how to choose and enjoy anything’. That’s also why I like CDs because you just put it on and you have to listen to it.

**It makes it a more durational work.

JS: Exactly. Give time. Less choice. Choice is the worst [laughs].**

Aircode is performing Glasgow’s The Glad Cafe on May 19, 2022.