“I realise I have written way too much stuff now for you so maybe will stop there but happy to continue declaring my love for composting if needed!” writes Jennifer Mehigan, closing out a nearly 4000 word response to what was meant to be a comparatively short focus feature. The Belfast-based artist and trained florist is sitting out a two week quarantine after handing over some IRL emergency relief work so she can see her mum, and she’s finished these essay-long interview answers in a matter of days. That’s on top of the artwork Mehigan so generously designed and donated to AQNB’s even my dreams don’t go outside—a curated album of songs and visual works to be released on April 22.

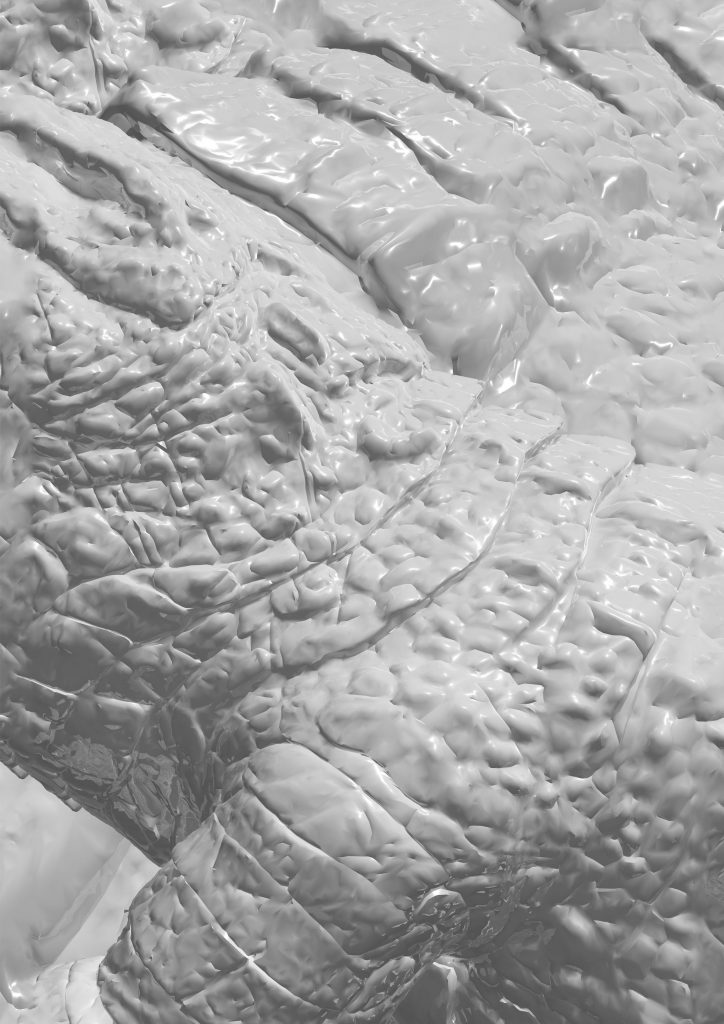

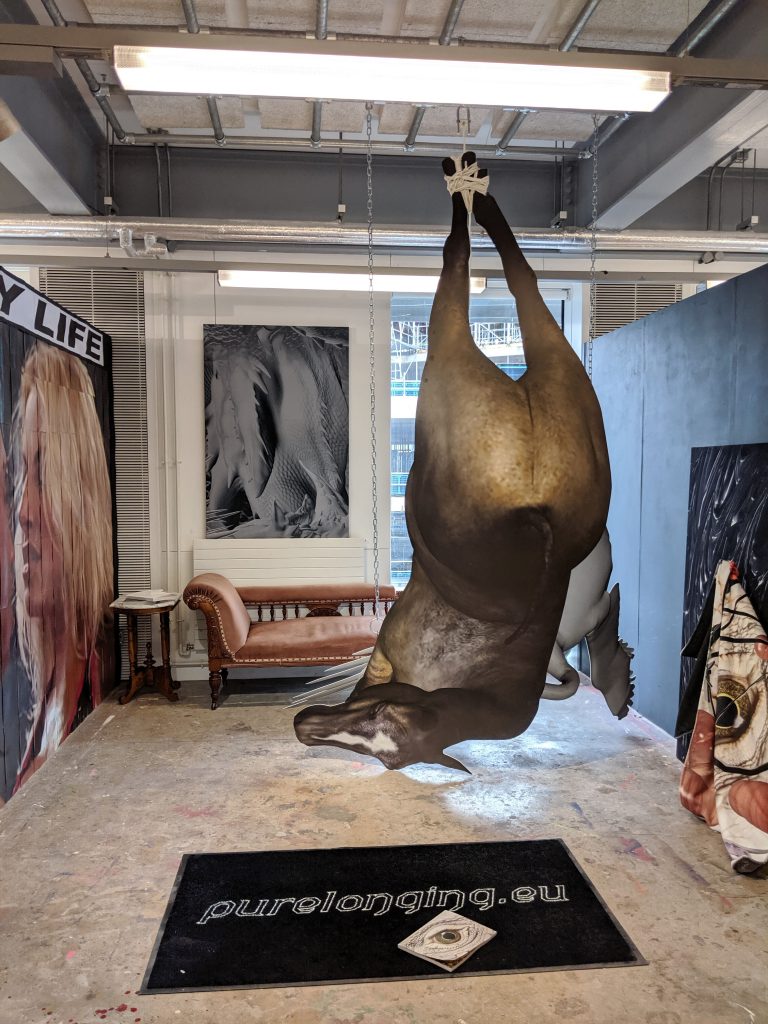

Meant to raise funds for and build positive momentum around contributing artists, the music and art compendium is inspired by the deepening overlap of virtual and physical space, particularly during this time of introspective self-isolation in front of computer screens. Mehigan’s work has for a long time existed at this liminal space between the ‘real’ and the ‘unreal’ that many of us are only now inhabiting fully during lockdown. As a late-80s baby of the Tumblr generation, the Cork-born artist spent her childhood and early 20s in Singapore; away from the usual cultural centres for art but still connected via the internet. The work to come out of that unique context included abstract CGI paintings of chromatic animal pelts and mutant figures. IRL installations complicated the understanding of an object and its simulation. Bodies and fetish objects were twisted and contorted across notions of Rule 34 kink.

Now though, after taking a year off from making art, Mehigan shares this collage of 3D plants—her own special compost of low poly rendered Irish wildflowers, some consider weeds. Cowslip and foxgloves, mallow, dandelions, daffodils and tansy are broken down in a collage of soil and worms from the artist’s own front yard. It’s somewhat representative of a slow shift into more embodied and material interests, since moving back to Ireland. Right now, Mehigan is completing a PhD at the Belfast School of Art on lesbian gardening in the country (north and south), from the end of the Great Famine to the present. She is also co-director of queer feminist group space 343, which has been running since 2018 and has most recently set up soup kitchens in north and west Belfast in response to the global COVID-19 crisis. With that, Mehighan has a lot of thoughts on compost puns, ‘fake hope energy’ and how we can all realistically help the people who need it.

Here’s the abridged version of the interview:

**Having followed you for a long time on Instagram, I’ve seen your aesthetic interests shift from this virtual fascination with the internet—sexuality and embodiment specifically—into a more environmental, ecological and I’m gonna say ‘archaeological’ perspective. Would you agree with this and can you tell me what compelled it?

Jennifer Mehigan: I think it’s largely geographical but also just kind of ties into a mental shift I went through in the past few years. I moved to a part of West Cork where both sides of my family had lived within an hours drive of me for hundreds of years up until WWII, and started thinking more intimately about history. I think in Singapore, even though it was my home for 23 years, I was a bit scared to ever connect with anything. Not just as an ‘outsider’ and it being a bit inappropriate but also because there’s kind of a fear that that things will be taken away from you because development moves so rapidly. So I guess I integrated the internet into my sense of object permanence.

Methodologically, I don’t think anything has changed too much really, I’m just able to cruise around in my car instead of just on my computer and I guess it maybe feels like the outside world started coming in because of that. Because of the weird immaterial or ‘unreal’ nature of life on a screen I think my relationship with my body and sexuality felt kind of abstract and unknowable, and I felt very dissociated from all physical forms so the idea of performing a certain way online made sense, to almost conjure up some concrete sense of myself. Now I feel a bit more like I am real and so is everything else, haha. It’s kind of interesting to see how that alone has opened up this space in me for (cringe) healing and calming down and participating in real communities, all that crap.

**It feels like we’re in this bizarre moment existing at the total collapse of IRL and URL realties, particularly as a lot of us are conducting our daily activities through networked communication. How has this moment shifted or reinforced your perspective and approach to your work, and life in general?

JM: It is super weird. The weirdest part of it to me is the feelings of being a teenager again. Memories are coming back so strongly of things I never thought I would think about again from age 12 to 17 maybe and songs from then getting stuck in my head. I’m working on sketchbooks and going back to basics because it feels like the right time for that but it all reminds me of being in school. I don’t think it’s just me either because middle and high school friends have been crawling out of the woodwork on Instagram and I’m sure a good portion of it is boredom but it might be a shared feeling? It’s just that now it’s not our parents keeping us home. I feel super privileged to be able to sit in my nice house and basically my work life has not been affected at all except that my travel plans were cancelled. Mentally, obviously the collapse and not being able to go outside is taking its toll and I am not necessarily able to make good work. I am in quarantine now so I can go back to my mom’s house for a while, and be able to go outside without people being nearby and I hope it will help a bit.

Ultimately, purely networked communication has always been my default setting so that wasn’t a transition I had to make, but it has been interesting to see the shift in people who are not comfortable with living that way. It has been a mix of pure LOLs and disgust watching art spaces navigate accessibility finally. Can’t wait to see how quickly they forget it all as well. :’)

**There are some very harsh truths that we’re being confronted with as well, people are suffering in a very real and immediate way. How has your attitude changed with these realisations?

JM: My eyes have been really opened by the extent of the suffering, especially in my own neighbourhood. I always thought I had a decent grip on reality. I think Irish people especially have a good grip on the shittier things in life because for the most part people like myself—middle class and in their 30s—are all only like one, maybe two, generations away from total poverty. There has always been this awareness of how much worse it could be for anyone at the drop of a hat.

I like that that sits on the surface of a lot of things here, especially the humour, but obviously there is such a huge difference between ‘knowing’ something abstractly and then getting a call or a text from someone who doesn’t have food for their kids tomorrow. I think confronting that is still happening for me, and I am not really sure what to do, or who I should be in the future because of this more embodied knowledge of other people’s lives. Is that weird?

Seeing how many people within one week of the lockdown were unable to afford food was so disturbing. We live in an agricultural country, and yet none of it is accessible. Even the narrative around allotments is quite a twisted middle class la-di-da-type of experience, when really their history is deeply rooted in the working class. Somehow it got hijacked or rebranded and almost taken away from the classes who need it most, like everything that is useful.

Late last year, I joined a small gardening group for a space called the ‘Peas Park’ in North Belfast, which is a community park and garden on a Catholic and Protestant interface, like 200 metres from my house. They are a great group of people who have been thinking about this for much longer than I have. They refuse to make it private or locked like a lot of allotments here, and so people can come in and take the food if they want/ need it. The turkeys and other poultry all end up causing traffic problems. Of course, it gets used mostly as a dumping ground but there is something kind of amazing about keeping it a genuinely accessible space and letting the crops be a free for all. There needs to be more spaces like this everywhere.

**What is some of the relief work you’ve been doing and how did you get involved in the first place, are there any relief funds you’d like to mention?

JM: The 343 itself set up a mutual aid type relief fund so that we could help members of our community pay for things they need at this time, like rent and hormones, because there was no encouraged rent freeze or pause. This will fund anyone who applies for it, but especially focuses on getting cash to people whose employment would not be recognised by self-employment furloughs and other things—like sex workers, people on zero hours contracts, homeless folk, et cetera. I think that ultimately people need cash in order to maintain their sense of autonomy in hard times and I think it’s really important to say that as much as possible, over and over again. Give cash.

I think in the queer community we already know that because we donate to our friends surgeries, and hormones, and funerals, and adoption funds, and all kinds of shit. There’s this understanding that nobody wants to really be asking but here you are, unable to afford things that can really mark the difference between life and death. Even the act of just caring for each other in times of crisis is so familiar in parts of the queer community and it was kind of nuts to watch people bury themselves into surviving as this individual thing and not looking to see who needed something more than them, but I guess that is the fun side of capitalism as always.

**Tell me more about the this ‘fake hope energy’ you mentioned in relation to these debunked animal stories that are cropping up. Does this have any relationship to this so-called ‘toxic positivity’ of a neoliberal ideology that isn’t acknowledging the structural inequalities that mean we are not, in fact, all in this together?

JM: Yeah, I think it will be so easy for this all to be twisted into a narrative that says like, ‘wow, wasn’t it better all along that the govt was totally incompetent and indirectly killed thousands of people because now the birds are singing more, and there’s clear water and less pollution’. I also just find it funny that there’s people out there writing fake news about things that aren’t even fake but they’re putting some weird energy into making it seem like they’re special? We live with these creatures all the time. There are orca whales in harbours randomly all the time, wild pigs and foxes et cetera live among us in cities, and we are so disconnected from the creatures we share our lives with. Super weird.

Obviously there are good things like less pollution and they’re able to measure how quickly it would take for the great barrier reef to recover if we hit pause collectively for a few decades, but it just seems much easier for people to think ‘wow, something good is coming of this! I can’t wait for things to go back to normal.’ There’s some major cognitive dissonance there. It is obviously much nicer to share the fake hope energy of magical thinking about dolphins, as opposed to the depressing reality which is like, ‘dear facebook, my neighbour might die of starvation before she even contracts the virus’. Grim.

**You mentioned Donna Haraway’s ideas of compost as the essence of femininity in relation to their being this resistant energy deep in the soil—at the same time as saying you don’t vibe with the “feminine mother earth energy thing”—could you explain what you mean by that?

JM: I guess the feminine mother earth thing can be empowering to some people but I just see it as an extension of domestic violence and femicide, and all those other things that happen to women. To me it kind of explains a lot of attitudes towards agriculture over the past few centuries with our really harmful farming methods and lack of wild spaces. Control and abuse feel pretty embedded into feminine experiences (obviously not all) but I kind of try not to participate in that whole mess internally. Haraway talks about it in a nice way in Staying with the Trouble where she writes, ‘Staying with the trouble requires making oddkin; we require each other in unexpected collaborations and combinations, in hot compost piles. We become-with each other or not at all.’

I think that kind of assembled, hodgepodge, rotting pile of garbage metaphor mirrors my relationship with my own body and fertility more than some lunar mystic femme floral thing. There’s probably loads of middle ground in there too. I am just bad at seeing it, ha ha. I can engage with femininity as a decomposing, steamy thing, but it’s hard through the other lenses I guess. It links back to all the abject things that socially we don’t relate to femininity but actually are, dirt, blood et cetera.**