“There, language was not that present at all,” says Ana Teo Ala-Ruona, recounting their earlier work predating their current focus on words and how those words influence reality. The usually Helsinki-based artist is wrapping up a month-long stint in Los Angeles with a going away party and a bewilderingly sizeable crowd of well-wishers are slowly filing into a Koreatown bar. They mostly, if not completely, come from the queerer end of the identity spectrum, which comes as no surprise given Ala-Ruona’s core concerns with maintaining trans and non-binary visibility and survival in a typically hostile heterosexual environment. “My experience of myself is always clashing so badly with the society that I’m living in that I feel that I do not exist and that my experience of myself, and my reality of myself, and my body does not exist.”

Visiting California in July for a series of events and an exhibition organised by mobile gallery Gas across venues, Ala-Ruona presented ‘toxinosexofuturecummings’. The performance is a provocative bodyfiction speculating on the role of queer ecologies within contemporary gender and anti-toxicity discourse. Covered in oil, the artist slips, slides and squirms on a swath of clear plastic, sucking, smacking and masticating into a handsfree microphone as their audience takes a seat in the darkened space of Chinatown’s Human Resources. Glowing alien green, the artist’s gaze is unwavering as it moves defiantly across spectators. Pale irises and dilated pupils trace the room, returning its occupants’ gaze and confronting their own voyeurism, as Ala-Ruona recites, “You’re fucking me in the ass with a sparkling, slivering, glittering, translucent, perfectly plastic dildo that’s wrapped around itself”. Satu Kankkonen’s sound design generates an ambient undertow of watery, squelching pads that unsteadily support the text’s themes that are equal parts academic and pornographic. Ala-Ruona’s parafictional protagonist ruminates on a childhood obsession with car exhausts and sexually explicit accounts of anonymous ex-lovers crossing biology, ecology and popular culture. “You pull me to your hard, plastic embrace and carry me to the back of your car. You push my face against your car tailpipe.”

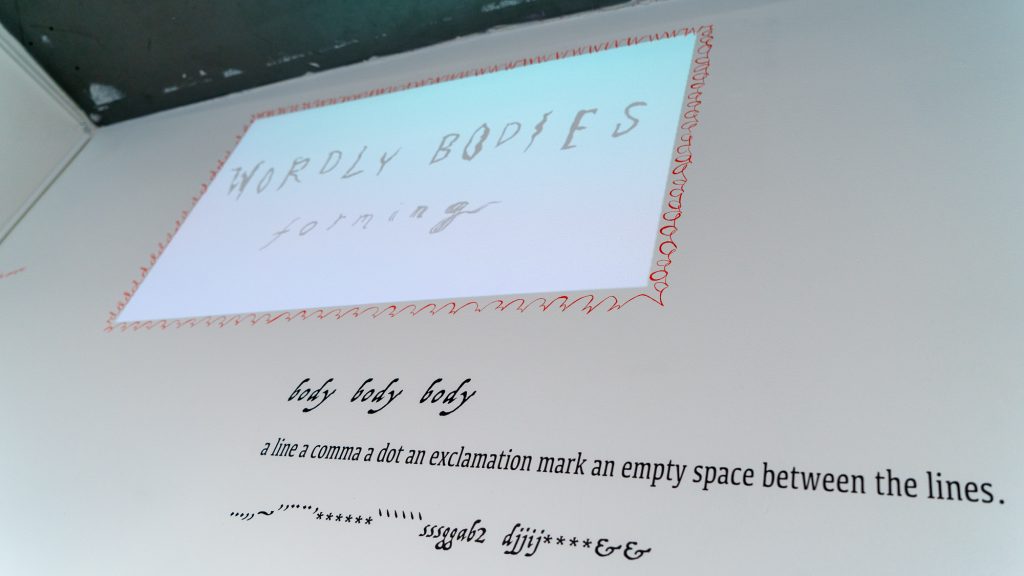

It’s in light of ‘toxinosexofuturecummings’ that the TWAH (=These Worlds Are Here) exhibition opening in Highland Park a couple weeks earlier gains newly eroticised meaning. Parked on the road outside Hikawa and Zizia studios, the rear doors of the Gas Gallery panel truck are swung open to reveal a gaping white space with blushing red text snaking its inner walls. They read in sentence fragments, like, “letters for a parallel reality to which the writing body extends”. There’s a mutating projection of the accompanying Worldly Bodies zine title in the centre, supported by a murmuring soundtrack of contributors reading their work, developed during a workshop at Navel in early July. “I love your face. Look at you,” reads Ala-Ruona’s disembodied voice, winding around and through the other spoken word pieces circling themes of the erotics of technology and somatic fiction. “Teeth, in the flesh, biting and penetrating, gently and firmly. A game without winner. My heart is a beast.”

It’s with this preamble—also prefacing an upcoming series of ‘toxinosexofuturecummings’ performances at Mad House Helsinki on December 12, 13 and 15—that Ala-Ruona took the time to speak about the politics of language, technology and gender across cultures.

**When you talk about the somatic possibilities of language to change the body, what do you mean by that?

Ana Teo Ala-Ruona: I’m thinking of how much words are used about my body by other people and people that make assumptions that go wrong affecting me every day, and how they form my experience of everything that I do. Also, how much those words also affect my experience of the body and the world when there is a chance for me to speak about my body on my own terms. There’s so much talk about whether words actually do anything—or is semantics or language even interesting anymore, and all that—but when it comes to certain marginalized bodies, realities, I think it has a huge effect on how those bodies can even exist.

**Could you elaborate on how the way that other people communicate your body affects your body?

ATAR: The way I carry my body, the way I kind of position and reposition my body, for example. How I move my body or what kind of tone of voice I’m using, and what kind of voices I might be trying to tone out from my way of speaking. Facial expressions. I guess it affects it on many, many layers, but the biggest one I’m meaning is the dysphoric moments that come from social situations where I’m misgendered.

**When you talk about the somatic shifts that occur in response to an external language being applied to your body, what shifts have you experienced while being in Los Angeles as opposed to Helsinki?

ATAR: This is obviously a topic that I could go on for a very long time because the Finnish language does not have gendered pronouns. There are situations where people obviously gender me, and gender people all the time in their heads, but it is not as prevalent in the everyday life as it is here. An example from today, I was in a Lyft, and again when the car turned to my street, my heart was racing at a super high beat and I almost felt like I want to close my ears because it’s very often in the end, when I say, ‘thank you, very much’, they say something like, ‘you’re welcome, ladies’.

I am more alert about every human being that I meet here than I am in Finland. Even though I am very alert of, let’s say, the gaze of people everywhere. I’m not alert all the time, but maybe just aware of them, and thinking very often, ‘what does that person see when they look at me?’ But here it has kind of gotten a different, next level, I’d say—the awareness or the alertness—because it comes through, where they kind of name it all the time. They name their gaze, and they they make it visible by their words.

**I’m interested in how the toxinosexofuturecummings text changed when you translated it into English.

ATAR: Elina Minn is the dramaturg of the piece and they’re really good with language. When they heard the English version for the first time, they said that it totally changed the piece for them. For example, the part where I’m talking about the cars and the car anuses, and I’m talking about my childhood memories; where I’m speaking about my excitement about the gas smell. Elina said that they could always transport themselves to the 90s Finnish landscape around specific looking cars, and when it was translated into English, they said that they couldn’t see that anymore.

I would have loved them to see the piece here because the culture with the cars is so intense, and such another reality than what it is in Finland. But I would say it changed for me also a lot. Of course, there are words that I had never heard—mucus glands, intestinal glands, all that stuff. I never knew that language, so I needed to find a relationship to words totally from scratch.

**This also operates on this false assumption that you can distill language and control its interpretation in some way. When you communicate a message, every person’s understanding and experience of it is going to be completely different.

ATAR: Exactly, yeah. And so many people who have seen the piece have been complimenting the text a lot but then many of them have been also asking, ‘could I read it? Because I didn’t get it.’ And I’m like, ‘for sure you don’t get it. It’s a one-hour piece with only speech, so you can’t get it all.’

I also learned the text as if I would be learning lyrics of a song. And that’s what I’ve been doing my whole life. The first English songs would be like Spice Girls, Backstreet Boys stuff. I kind of learned them really easily after a couple of times of listening to them.

**Is it a musical thing?

ATAR: I think it is to some extent. For example, the part when I’m singing live in the piece did not exist in the Finnish version at all.

**The song the was pre-recorded, as well?

ATAR: No, that’s, Evanescence [‘My Immortal’]. That’s a hit from the 90s. No, the millennium.

**That’s a common narrative, of people having their first introduction to the English language through pop songs.

ATAR: Yeah, exactly. That was kind of my gateway to it, for sure. And Metallica, actually, because my brothers were listening to it so much when I was a very, very tiny person. But then we start learning English at a very early age in Finland.

**This cultural hegemony—in terms of this network of language and dispersal of information, as well as the spread of chemicals through technologies—there’s this element of virality to all of it, which is how popular culture also operates.

ATAR: Thinking back on it, I realise that there are more popular culture references in the Finnish version, I would say, for the audience actually to read because there’s parts which I say in English in the Finnish version. There is a part where I say, ‘I’m over sensitive to and it’s wonderful. It’s all I ever wanted.’ That sentence I would say in Finnish, except I would say ‘it’s all I ever wanted’ in English because it’s a very much a popular culture thing, from a Britney Spears song, or something like that. So now when I’m actually thinking about it, it’s definitely an accurate read of it. It hasn’t ever been the main focus of the piece but for sure it’s there. And, for sure all the references that I’m having in it are references from my childhood, from my youth, which kind of refers to an era where your body is changing due to puberty and stuff. I guess I’m just thinking of that in a different way now.

**Can you also tell me about the costume and mask Alvi Haapamäki chose for the performance?

ATAR: I wanted to have different coloured eyes because contact lenses are things that change your face immediately, so much. It makes it very weird and unknown for people who know your face. I wanted to do some sort of alienation from the ‘Ana Teo’ of me personally, autobiographically, on stage but I didn’t want to put on a full-on costume, let’s say, like a dinosaur thing [laughs]. I wanted something that makes an immediate change to what I look like usually.

It also serves me because the piece is so much about gaze, and me watching people, and talking to people through words, but also talking straight to their face and looking at them. I know that the piece has a lot of intimate stuff and I felt a needed to do some sort of distancing.

**You’re also covered in oil. What is the significance of oil and gasoline as a substance, apart from how you described its effect on your body, as a substance that seeps into your pores?

ATAR: That’s the main thing about it but also, in the post-fossil fuel era ecology discourse it’s seen as the substance that created the whole Anthropocene, or whatever you want to call it. Oil is the reason for the ecological catastrophes we’re facing now, and the crisis around toxicities affecting human and other nonhuman bodies in the world is talked about from the perspective of the trans-sex panic, or a transgender panic where, ‘Oh my god, the fishes are turning into intersex fishes. More human intersex babies are born’. It’s not at all focused on cancer or autoimmune disease but it’s about the panic that, ‘Oh my god, gender is being lost’.

**It could also be that changing attitudes to gender and sexuality are making it easier for people to become visible.

ATAR: Exactly. I’m definitely not trying to advocate for any kind of pro-toxicities discourse but the anti-toxin discourse is very white, very male-centred, very Eurocentric, very problematic, and very gender essentialist. So the piece is to some extent saying, ‘If it’s these toxicities that caused my non-binary gender, I guess I’m grateful for those toxicities’. **

Ana Teo Ala-Ruona is presenting performance toxinosexofuturecummings at Mad House Helsinki on December 12, 13 and 15, 2019.