‘I’m interested in bringing objects across this physical-virtual divide and seeing how they mutate each time they are re-created’, Theo Triantafyllidis tells fellow artist Faith Holland as they sit down to discuss his recent solo show, Role Play which ran from April 21 to June 9, 2018 at New York’s Meredith Rosen Gallery.

An architecture graduate turned artist, Triantafyllidis works with machine logic and interactive spatial constructions to evoke the contemporary experience of the virtual and question the relationship between human and machine. For ‘How to Everything’ in 2016, he made a computer generated animation where objects hypnotically emerge from and collapse into one another. Making a purposefully random algorithm visible, it plays with our expectations and the human desire to find patterns and place meaning on how these objects relate. Then in ‘Staphyloculus (or the paradox of site specificity of virtual realities)’ (2017) he created a one-person VR experience depicting the outbreak of a mysterious virus called Polywobbly Fervenitis. Again playing with our point of view by producing an alternate reality within the gallery space that carries on regardless.

For Role Play, Triantafyllidis extends his interest in the physical/virtual but this time to explore the concept of labour — on one hand the significant effort that goes into the construction of digital objects and on the other (as the title of the show suggests), the performative identity of The Artist.

Upon entering, visitors are presented with a seemingly still room — the scene of the artist’s studio filled with half-made objects and paintings — however it becomes quickly apparent that someone else is there. “Check out my new studio… Finally, I have enough room to make things,” says a distorted voice. Using the large screens mounted on rollers, visitors can track about the space to find a brawny Ork with long blue hair and pointy tusks — Triantafyllidis’ avatar — busy at work on one of the paintings. There’s a dynamic tension there, where everything is partial, made temporarily complete only through the presence of the viewer.

And this is my new body.

My old body felt so uncomfortable and saggy.

Now I am strong.

And I am sexy.

Do you like my hair?

Identity is a long-time interest of Triantafyllidis’ partner in conversation, artist Faith Holland. In particular, the New York-based internet artist looks to explore the performance of gender and the role that the technical infrastructure of the web plays on its construction, as much as the emerging social space around it.

Below, Holland talks to Triantafyllidis about his intentions with Role Play, the so-called ‘queering’ of Ork aesthetics and the move from VR into AR.

Faith Holland: How do you see yourself as an artist in relationship to the Ork?

Theo Triantafyllidis: The whole process started from thinking about virtual reality and thinking about embodiment in VR. I found this very DIY way to do a full-body motion capture and I was immediately interested in thinking about what my avatar would be. The whole avatar discussion is something that has been around for a long time. LaTurbo [Avedon] is really killing it. I wanted to think about what happens in my own body when I ‘wear’ an avatar. The beginning of this exploration was making a few different bodies and seeing how my brain reacted to them. The 3D body software I was using was all parameter-based, so you could tweak the parameters to be like 80% muscular, 30% pregnant, and 10% Ork, for example. I thought: what happens when I stretch these parameters outside their limits and dial up all the numbers? These particular 3D models are very recognizable. A bunch of artists and industry people use them. I wanted to push the avatar in a direction that was simultaneously very stereotypical in some ways, in that it was all these video game characters smashed together, but also slightly different from that. When I was making the avatar, I was so attracted to it in so many ways. I can’t exactly communicate why I wanted to be this Ork so much. I hope it is noticeable throughout the work that there’s this element of coming to terms with what this body means and why I’m doing this. I didn’t want to resolve it ahead of time.

FH: So you’re using the Ork as a kind of conduit to make the physical work that’s in the show. So much of this show is about practice — the act of being an artist and how to perform that. Are the works made by the Ork/you in the physical space through this digital performance, or are they made entirely in advance and then the Ork enacts it? Like, are you creating that painting as the Ork, or is the Ork animating something you’ve made previously?

TT: The painting was a one-take. The fifteen minutes of the video is the time in which I actually made the painting, and I made it as the Ork. I chose this specific genre of video game fantasy character because the fidelity of working in VR is not great. I thought the Ork’s brutality and roughness would match that well. The other aesthetic aspect of the Ork’s work is the idea of ‘form follows function.’ The types of devices and weapons that Orks use in fantasy games are always very modernist in the sense that their form is simply the best way to destroy stuff, or the simplest way to make something. I thought this was a funny comment on modernism and how you can get to simplicity either by extreme sophistication or by sheer stupidity, in a way.

FH: Are the Orks known for destruction?

TT: Yeah. Orks are always represented as these stupid warriors whose whole purpose in life is to kill and destroy.

FH: So there’s a kind of ‘nothing-but-the-body’ thing going on. I love when you said that you were ‘wearing the body.’ Does embodying and working through the Ork allow you to make a different kind of work than you normally make as Theo?

TT: Yeah. At first, I didn’t have a clear aesthetic goal. The process was: become the Ork, gather found 3D models, make some more models myself, and then start to assemble these ideas into forms and sculptures.

FH: That reminds me of this one Ork line that I think is hilarious. The Ork says: “If I want to be a bad boy artist, I have to make it bigger!” There’s all this genderqueer stuff going on with the Ork. I’m wondering how that all fits together: this butch-femme Ork who wants to be a bad boy artist and is making this really aggressive work.

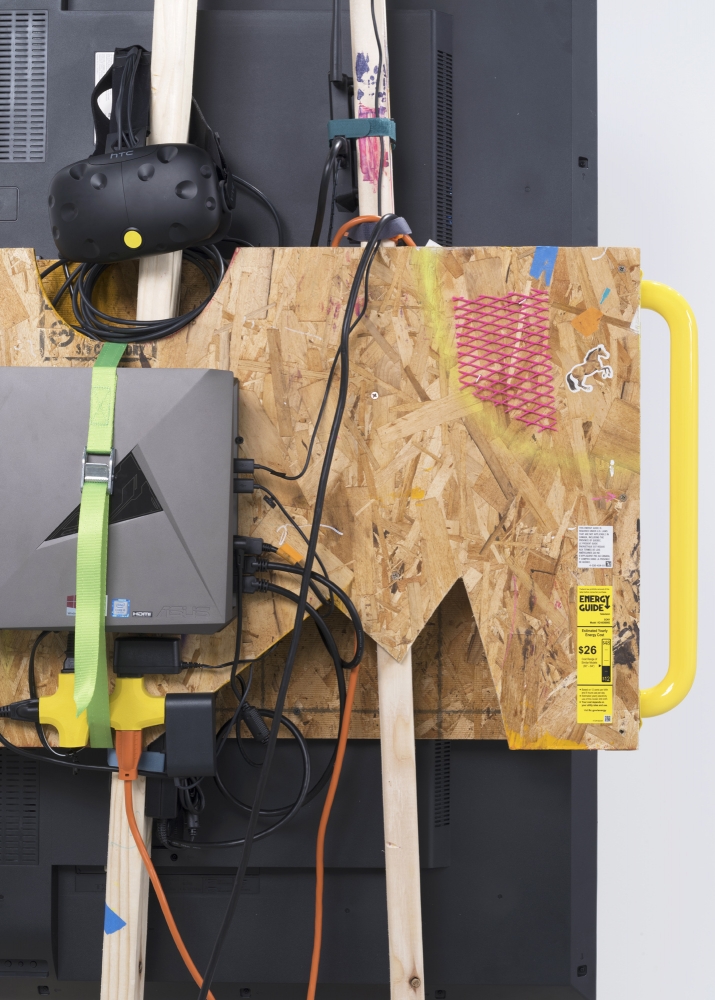

TT: I was trying to do a new take on the “bad boy artist” genre, queering it as much as possible. The reality of making this work was me wearing a headset and working inside a bedroom studio with a small computer, while fantasising about being able to make these gigantic sculptures and fantasising about having this huge space to work in–

FH: –– with a beautiful view.

TT: ‘Bad boy artists’ have a ‘badass idea’ and then 20 people fabricate that for them. The sculpture is often pretending it was made in a very sketchy way, but in reality, the physicality of making it is so much more complicated.

FH: It’s interesting that you have this three dimensional virtual space, but then the sculptures are super-flat.

TT: The physical sculptures are snapshots of the 3D pieces printed on plywood, so it is photographic in that way. The labor that went into these pieces was in VR, so it didn’t make sense to try and make them the same way in the physical world, because that would require the actual labor that I was trying to avoid.

FH: Your work is pretty heterogeneous, but this piece in particular seems like a departure from your previous work of setting up parameters and then letting it happen. Whereas with this work, you are performing through the work and it’s pretty finite in a way that the other work isn’t. What caused that shift?

TT: I was always interested in the performative aspect of the work, even if it wasn’t me performing. My actual bodily presence is very awkward, and I don’t feel comfortable performing. This whole complex apparatus was a way for me to hide that a bit and to feel more comfortable performing. Being the Ork helped me get over some of my difficulties.

FH: I want to talk about the meta relationship that the Ork has to art. I think this also appears in some of your other works like How to Everything: there’s like this spectre of painting that stands in for art with capital A. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about your relationship to painting.

TT: My reaction to painting is really visceral and simplistic in a way. I actually don’t get painting and I don’t understand why people do it. But if I tried to talk about that in an arts context, everyone would look at me like I was from another planet. Being the Ork gives me an excuse to say things that maybe people are thinking but are afraid to say because it might sound dumb. That’s another part of using the Ork to mask: to just talk straightforwardly and simply about things. I hadn’t painted before, and I mean this is a really simple version of painting–

FH: —Or a very complex version. You have to embody a character and perform the painting, you have to print it, and then transport it somewhere else. It’s actually very complicated.

TT: A big part of making the work was building the behind-the-scenes framework: setting up the recording and programming the interactions. But the final step of creating the painting was just 10 minutes, so it was a very enjoyable experience. That was my way of actually trying to paint.

FH: Let’s talk about how it exists in physical space from the viewer’s standpoint. The fact that we don’t have to exist inside the VR goggles is super liberating. How did you envision the physical interaction of the viewer to the work, particularly with the monitors on wheels?

TT: I’ve done a few VR pieces recently, and thinking about the audience was the number one concern. And that includes thinking about how people will experience it, but also how other people will experience someone being in VR. Like in a previous VR piece that I did called Staphyloculus, the whole piece is secretly choreographing the body of the person in the VR set to do weird stuff for the other people to watch, without that person necessarily noticing. With this work, in the same sense, I am gamifying the viewing experience. You have to actively participate in viewing the work and finding the avatar’s performance. I’m also getting bored of having headsets in the gallery. I wanted to make the experience more sociable and exciting and accessible for the audience. Having these large monitors activates a more collective engagement, like when two people dragging the monitor around the room becomes a dance of its own.

FH: Yes, it’s a much more social experience than the individual experience of the goggles. Going to a gallery can actually be a very social experience of seeing work with other people. There’s that lateral energy, which I think this piece brings back into the gallery space.

TT: And if you do augmented reality on an iPhone or iPad, it’s still a personal portal. It’s not so easily shared. There’s also all the hassle of installing an app and scanning the barcode to even get started. The other important reason for the large monitors is so that Ork is to scale and you feel its presence in the space.

FH: In the large installation, the Ork feels like a ghost circling around you as she creates.

TT: That’s what I really love about AR. You can achieve a sense of presence with the augmented characters in the physical space. Even if the monitors are not pointed at the Ork, you still feel her lingering presence.

FH: Right. Even when I cannot see the Ork, I can hear the Ork. The presence is still felt, and that can guide the visuals. One more question for you: your use of humour seems to be a consistent strategy across many of your works. I’m wondering how it plays into this work.

TT: I feel like we share this approach. I see humour as the vehicle that will draw people in and get them to engage with the work on the first level, so that the work can then guide them through the other things that are going on. I really appreciate humour in art. My type of humour is not very textual, but visual and performative. Which is why I’ve liked working through the performative elements of this work, because it has helped me find new ways of expressing humour.

FH: There’s so much about the Ork’s physicality that is funny. There’s an element of slapstick, like when the Ork throws objects onto the sculpture or thrashes the paintbrushes. Do you think you’ll do more work as the Ork?

TT: Yeah, I think I will. There are a few aspects of the Ork that I haven’t yet explored. A small hint is that it’s going to be about athletics and exercising in VR. The other aspect of the Ork work that I’m really interested in is the site specificity. I’m hoping someone will invite the Ork to do site-specific work in another location. The Ork working in nature and doing some land art would be fun.

FH: The landscape outside the Ork’s studio looks like a great place to do some land art. Those beautiful mountains, right?

TT: Exactly.**

Theo Triantafyllidis’ Role Play at New York’s Meredith Rosen Gallery ran April 21 to June 9, 2018.