“The point was conviviality, a deep kind of sociality…The most important thing was gathering in that tiny kitchen, talking, having a drink. These small congregations are the most important entities. Ideas come from individuals and in group formations they have more chance for survival.”

– Victor Skersis, as quoted in Anti-Shows: APTART 1982-84

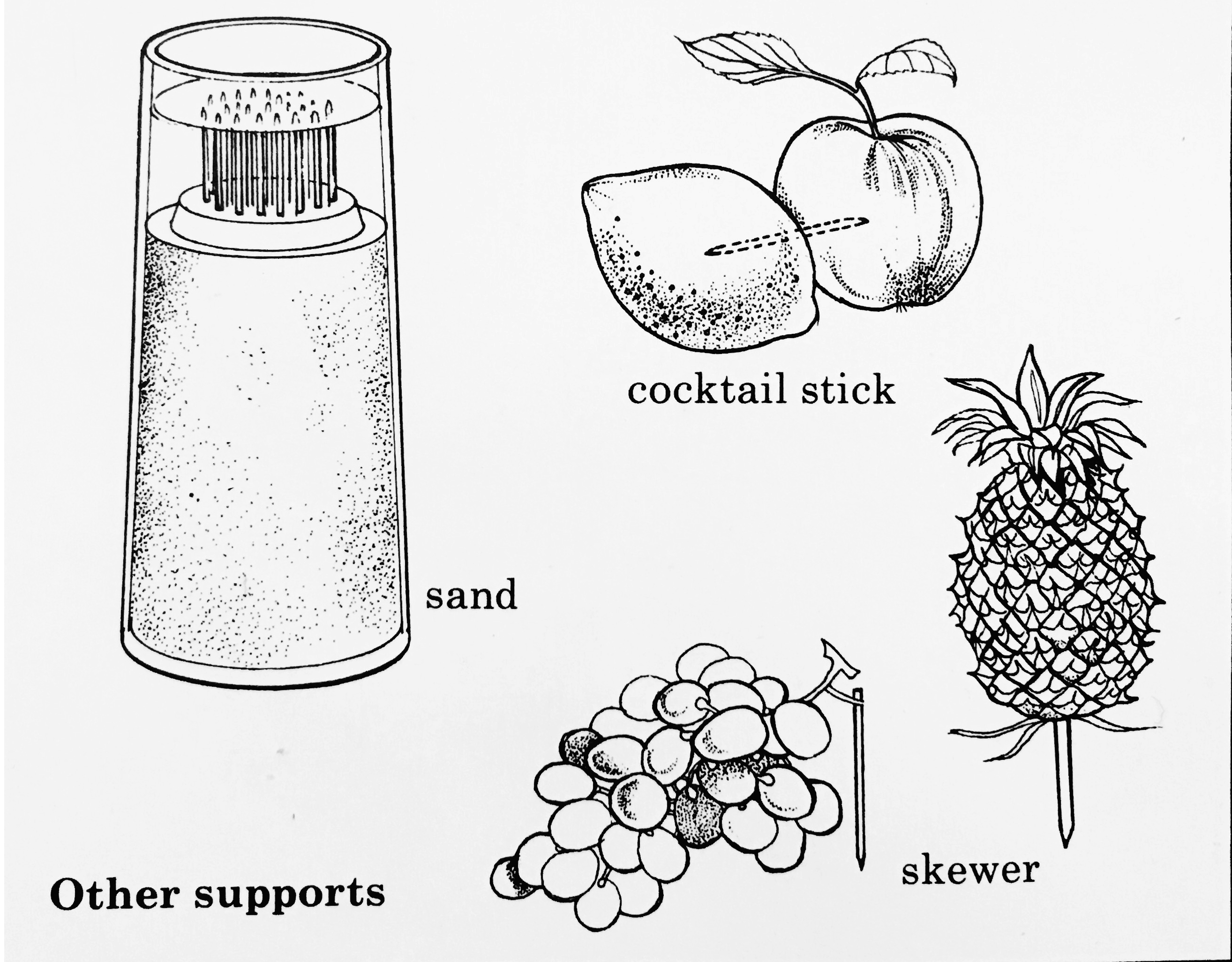

Credit: Other Supports, found image.

Can we begin with the gathering in the kitchen? In a moment in which so many aspects of our life and work is required to be present, documentable, in order, in shape, profitable, describable, it’s hard to imagine how. And in the city I live in (London), where the cost of living, movement, access, exhibiting keeps rising, the spaces for unplanned encounters, sharing a drink together, experimenting and not quite knowing what will happen seem to be disappearing. We need places in which we can try out what works and what doesn’t so we can figure out how to sustain and make better what it is we want to put into the world. We want spaces for personal health in the way Sara Ahmed suggests in Selfcare as Warfare: “through the creation of fragile communities, assembled out of the experiences of being shattered. We re-assemble ourselves through the ordinary, everyday and often painstaking work of looking after each other.”

As buildings are snapped up by property developers, studios close and rents increase, independent and artist-led projects have to move or change shape in order to maintain a practice and find ways to keep each others’ practices going. In 2015, the GLA’s report Creating Artists’ Workspace estimated that 3,500 artists are likely to lose their workspaces over the next five years. As a producer and curator, my own practice has developed by both working inside institutions — and outside, as part of collectives including Black Dogs, Wish you’d been here, Bare Plume and The Caged Antelope. Using a DIY approach to running projects, parties, bars, club nights, hosting is an important feminist method for being generous, welcoming, and creating spaces for people to come together. So now, in this current context, one wonders how to keep providing the opportunities for experimenting, exhibiting, learning, hanging out, and making friends.

Since 2010, I’ve run 38b from my living room in Peckham with my partner Luke Drozd. Connecting to the historical legacies of APTART — a series of self-organised experimental ‘anti-shows’ which took place in private apartments in Moscow, Russia, between 1982 and 84 — 38b started from a desire to create space. This was a space for ourselves and others to test ideas amongst people we know and trust, making things happen using what we have, and bringing together friends who should know each other but are yet to. As we were already paying rent for our flat, the most immediate, cheapest way to do this was to transform our lounge. So 38b began to take away the pressure of having to have substantial savings or apply for funding in order to do things. 38b doesn’t generate any income, it happens in our spare time and we both have jobs which cover our costs. Because 38b happens where we live, things can happen quickly, we can decide what we do and when — as it’s built on an understanding that no one is profiting from it — and we have been able to let people do what they want and see what happens. Our first exhibition ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXY etc attracted just ten or so friends. Now, sometimes over 200 people come through the apartment over a weekend. The artists we invite use it as they need — either stripping any trace of our residence into a white-walled gallery, or embracing its domesticity. Sometimes the room is emptied of furniture, sometimes it’s full. Sometimes we hide the sofa, sometimes we have to make the show around it as there’s nowhere else to put it.

We began in a context of diminishing areas for artists to work and exhibit in London, and since we started, the number of domestic art projects in the city has increased. These have been important circumstances for 38b to grow from, but what we’ve learnt through it is not just about finding a way to continue to exist against all odds, but about the importance of carving space for practicing, testing, and socialising. 38b has always worked toward an ethos of organising in the hope that something will happen, and not in the fear that it will not.

During this time, we’ve found mutual support with others in London using their homes including Rosalie Schweiker’s flat, which co-hosts The Pizza among many other things, Ladette Space, Fran Cottell’s House Projects, Furnished Space, and 113 Dalston Lane. At the same time, we’ve investigated other examples of domestic spaces as sites for learning, exhibiting, getting to know each other, to understand what kind of situations and relations can happen in our homes that can’t perhaps be produced in art institutions. These include IDEA – zelarrayan International Domestic Exhibitions by Affinity, The Copenhagen Free University, The Grand Domestic Revolution at Casco and The Showroom ‘Why do it at the Tate it you can do it in your living room?,’ co-hosted with Rosalie Schweiker and Maria Guggenbichler, and the Radio Anti Domestic Transmissions were organised as opportunities for us and others to discuss how we can keep our activity going beyond the living room, without compromising our principles.

In autumn 2017, on a residency in Barcelona with BAR project, I encountered echoes of the struggle to keep going. Online hosting service Airbnb has pushed rental prices up to similar levels as London, and the independence referendum in Catalonia, which began when I arrived in September, led to the sudden blockage by the Spanish government of resources to public institutions in the Catalan capital. Many projects were forced to shut down. People are now having to work out how to keep things going without institutional support, using their personal resources and energy, and organising themselves to make it possible for others. Many independent art spaces have recently closed — including Fireplace (who now keep it going nomadically) and the long-running, much-loved bookstore Multiplos. They lost their premises to new developments, increasing tourist-focused rents, and the energy it requires to sustain something on nothing. At the core of both of these organisations is a dedication to providing a place to share and test things collectively. Other domestic spaces, including Halfhouse, el passadis, Festival Plaga, Homesession and the conversation series Esnorquel, hosted in curator Sonia Fernández Pan’s kitchen, also have and continue (as the artist Quim Pujol who ran La estrategia doméstica from his home in Barcelona) to ‘make space for others to come in’.

Nyamnyam, run by artists Iñaki Álvarez and Ariadna Rodríguez from their kitchen in Barcelona’s Poble Nou, is organised around cooking and eating together. Without funding, or wanting to become a fixed model, nyamnyam run regular intergenerational events which aim to promote creativity and knowledge exchange. They design collective actions in which everyone has a role in producing the food, as a way to shake up existing relations and get people to talk, share, meet while chopping, toasting, boiling, reading, serving next to each other. For them, these small moments of collective decision-making and co-working that happen in the communal kitchen cannot easily be summed up, but they recognise this is an important space for encouraging conversation that leads to unexpected places.

“It’s clear it could be a lot easier but we look at things through this lens because it’s a way of life,” Iñaki from nyamnyam says to Anna Dot in a 2016 interview for A*Desk Critical Thinking “What is central is not the food, so much as the moment of sitting together at the table, cooking together, or sharing a particular hour, which is the hour of eating. The food, as a result, is not important.”

When I first met Iñaki and Ariadna, we both had been separately introduced to The Bloodroot Collective, a feminist restaurant in Connecticut, United States who have been going for 40 years. The self-sustaining business, of which two of the original collective members still provide the foundation for Bloodroot today, acknowledge the writer and civil rights activist Audre Lorde, their friends, passersby, washer-uppers, each other, their mothers, their feminist politics as constant inspiration for keeping going. Their cookbook and personal reflections on their work, The Second Seasonal Political Palate produced in 1984, was used as the starting point for ‘How does she keep it going?’, the first event in the programme ‘Como imaginar una musea?’, which I co-organised in Barcelona [with BAR Project, Adrian Schindler, Ariadna Guiteras, Ariadna Rodriguez, Caterina Almirall, Eulàlia Rovira, Jordi Ferreiro, nyamnyam, Priscila Clementti, and Sonia Fernández Pan] during my residency to reimagine the ‘museo’ (museum), which is a masculine noun in Spanish, as a feminist ‘musea.’ The series of events began at nyamnyam, moving into a museum and then an independent project space throughout November of last year, to conjure up a feminist cultural institution run on priorities of friendship, hospitality, care, collaboration, socialising and experimentation.

“We live our work and our work lives,” write the women from The Bloodroot Collective, “Our rewards are daily because we live what we believe. Yet, maintenance requires commitment, devotion, and lots of hard work. It means our beliefs, actions, our behaviour, are all part of this intensity, this consciousness of extremity. We choose this consciousness.”

Beyond Barcelona in Bilbao, I met Beatriz Cavia, Miren Jaio, Isabel de Naverán and Leire Vergara who have been running the project space — which also functions as their office, meeting room, residency base – Bulegoa z/b for the last eight years. As a collective, as well as mothers and freelancers, they have kept it going by resisting the pull to be present all the time. They keep their costs low by only opening the space publicly when it’s needed, and recognise that at the same time they can provide somewhere important in the city for artists to test work, rehearse and use as a temporary studio. “Bulegoa z/b adjusts to our lives, we don’t adjust to it,” says Leire. However, if the activity of an institution is not constantly visible, and instead focused on caring for relationships, encounters, learning in private moments and doing what is possible, how can we justify this to our funders — and ourselves — as still being important and productive?

During the research for ‘Como imaginar una musea?’, the essay ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’ by Ursula K. Le Guin helped to think about this ‘on/off’ conflict. The fantasy and speculative fiction author re-imagines history through a lens of the container as something which gathers, nurtures, protects the relationships inside it. That’s as oppsed to the pointed stick (or the visible, engaging, documentable art programme), which conquers and forces itself into other people’s spheres and lives. “We’ve heard all about all the sticks, spears and swords, the things to bash and poke and hit with, the long, hard things,” writes Le Guin, “but we have not heard about the thing to put things in, the container for the thing contained. That is a new story. That is news.”

If we use Le Guin’s theory of a container, which shape-shifts to respond to what is needed, can we imagine a way to keep going based on reacting to what our workers and visitors need, rather than our funders? Could this extend to creating accessible, shared space built on advocating equity for those who have lost space, face reduced access to opportunities or simply don’t feel in a safe in an area to continue their practice?

If we imagine our programmes becoming less about always being visible and more about protecting space for ourselves and others to test things, take risks, learn, fail, and re-learn as we go along, then we need to shift institutions and funders away from the need to have clear outcomes in order to prove what they’re supporting is ‘productive’. If we already own/rent/have access to a space, then let’s make it accessible to others to use for their endeavours, even if it doesn’t enhance our own visitor figures. As an example, at London’s The Showroom the studio is regularly given over to different groups from the local area around Edgware Road and all over the city to use outside of opening hours for meetings, classes and closed workshops. What happens in these ‘non-public’ moments may not be visible straight away but they provide important opportunities for the groups to work through things among a close community, the outcomes of which may only become visible a while later.

The question ‘how do we keep it going?’ is as much about finance and administration as it is politics. To keep a vegetarian restaurant going for 40 years, requires good financial organisation as well as feminist politics and commitment. This article is too short to explore models here — beyond the living room — for supporting not-visible-at-first activity, so now I’m thinking of how to encourage funders, our institutions and ourselves to put the emphasis on keeping spaces for this kind of work open and sustained.

38b is now at a point of wondering how we keep it going in (or out of) our living room, as demand from artists and others for testing grounds keeps growing. Making space for things to happen requires hard work, time and maintenance. We all know it and at the moment perhaps it’s harder than ever. But let’s keep it going. Because we have things to say and share that matter. And if we’re going to keep it going, then we need to remember the importance of the gatherings in the kitchen — or in ‘la musea’ — the private spaces, test-spaces, social spaces, that give our hopes more chance for survival.**