“It’s the antithesis of the neoliberal archetype of the white box,” writes Alessandro Bava about his long-time interest in recuperating non-secular approaches to space by borrowing from the oriented displays of a Church and applying it to an exhibition. “It is interesting how, in religious spaces, there’s always a ritual/ethical motive attached to form.”

Installation view. Courtesy the artist + Mackey Apartments, Los Angeles.

The artist and recent architect-in-residence at Los Angeles’ MAK Center spent six months at the Mackey Apartments with London-based resesrm åyr (formerly Airbnb Pavilion, and including Luis Ortega Govela and Octave Perrault) from April to September, 2017. There they delved into the dense and complex historical, natural, spiritual and, of course, architectural map of the city, to provide a broad and fascinating insight into its composition with a three-month programme of six events, running July 7 to September 1, 2017.

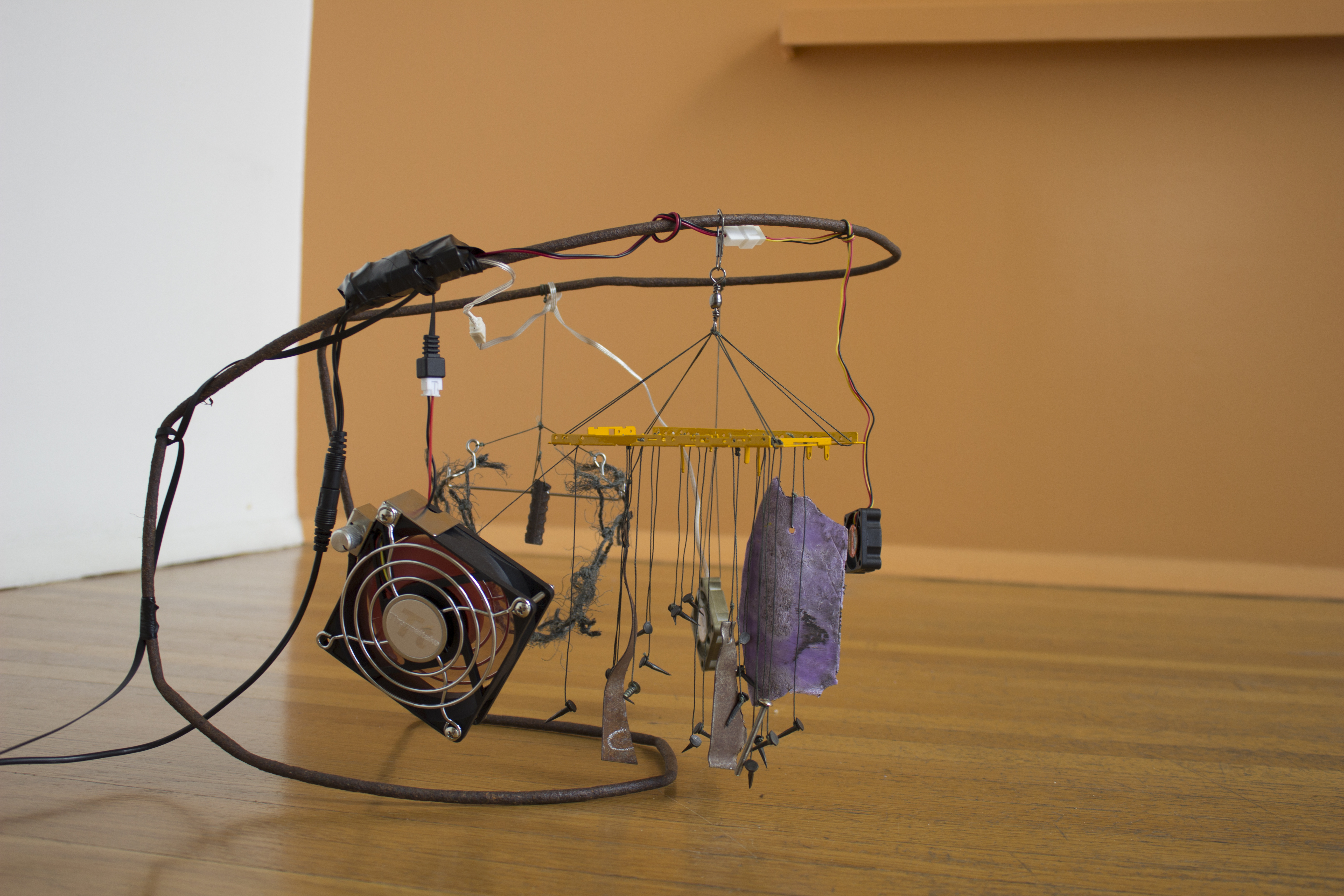

Frustrated with what he calls the “implied globalism” of the art world, Bava and his colleagues decided to pull focus onto their immediate surroundings in Los Angeles, presenting a diverse exploration of the layers upon layers of socio-cultural information that make it up. The outcome was the experimental wind-chime constructions of Riley O’Neill’s Designed in California exhibition, DeSe Escobar’s Winter Turns to Spring, and Ramsey Alderson and Paul Levack & Sam Lipp’s Apologia show. There was a tour of the mirror glass architecture that has come to define the post-industrial corporate landscapes of LA, led by local Daniel Paul, as well as a rendering of the Spanish Franciscan roots of what was originally a military outpost called El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles del Río Porciúncula. Translating to ‘The Town of Our Lady the Queen of the Angels of the Porziuncola River’ in English, the group exhibition, curated by Bava, was organised around the intentional axial vector of a Christian Church.

To finish it off, åyr presented their research into the hillside city of Los Angeles County’s Calabasas area, one famous for its resident media influencers — Kim Kardashian, Kanye West, Drake — and a symbol of the widening gap and separation between the rich and the poor via gated communities on the city limits. Presented poolside of architect Rudolph Schindler‘s Fitzpatrick-Leland House in Laurel Canyon, Open House examined Calabasas “as a paradigm for digital urbanity and of post-cinema Hollywood,” as well as the role of its artists and architects in the process of gentrification.

**I’m curious about your practice-at-large, how you’ve come from architecture into curation within an art context, how did you get there?

Alessandro Bava: I’ve come to now describe what I do as a creative practice beyond disciplinary boundaries. I am interested in space and studying architecture has given me a competence in that, but I don’t really practice as an architect. Architecture and design are interesting to me as a form of knowledge, a form of craft which can imagine the future and analyze the present, a political art of projecting.

As augmented intelligence develops and challenges our understanding of the human brain, words like ‘creativity’ and even ‘design’ should be reclaimed. While these words have been abused by the neoliberal creative economy, it’s important we reclaim and re-describe them as essential human faculties. So, in this new context, I especially appreciate artistic expressions that are propositional and ‘creative’ because if art becomes just a question of erudition and esoteric communication it’s boring and useless. I like art that is ‘useful.’

**Housing and infrastructure is obviously of ongoing concern to yourself and åyr, what about it draws you to it in the first place?

AB: With åyr, we were interested in how technology is changing the realm of the home. We saw domestic space as an interesting domain which held immense political potential, especially in a moment where it was being made more ‘public’ by emerging technologies like Airbnb and smart home. We said in a text that we need more private space, a provocation against decades of cries for more public space, which has led to Faustian pacts between the public and the private (see London’s semi-private corporate public spaces). We are in a paradox where the private domain of the house, which in the Greek word was the essential nucleus of the economy, as opposed to the public space which was intended as the ground of politics, one could say that now politics start within, in the closed individual space of privacy. Also, åyr started in London and housing here is a humanitarian emergency.

**You mention that the MAK residency program tried to propose research in the ‘queer space,’ can you tell me more about that?

AB: This is an ongoing interest in the undoing of the intrinsic normative nature of architecture and space. I am interested in the application of queer theory to architecture, especially in a moment where we really need to question how we inhabit the world. In the future all space will be queer! (see ‘Joel Sanders on the past and future of gender issues in architecture‘)

Open House was for me an experiment in inhabiting the domestic space in more or less subversive ways, challenging the built-in power dynamics and the implied ethics of inhabiting such space. In fact, the most important thing was that every show happened in a different part of the 1938 building where the residency takes place.

**There’s this thread of physical infrastructure reflecting social, philosophical, religious, even spiritual realities/ideologies in, for example, the El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina… show, along with an awareness of this digital infrastructural ‘plane,’ particularly with Octave Perrault’s research on Calabasas, which (given its presence as a hub for social media personalities) exists simultaneously within these two universes. I’m curious what brought you (and åyr) here to this very complex and compelling realm?

AB: Overall the idea of the Open House program as an enquiry into the domestic should be seen as falling into åyr’s line of research, within that I wanted to explore more personal ideas related to identity (DeSe, Paul and Ramsey, Sam), spirituality (Pueblo) and craft (Riley). Initially, I was interested in practices which challenge disciplinary boundaries, ie. design, photography, clubbing and creative direction etcetera.

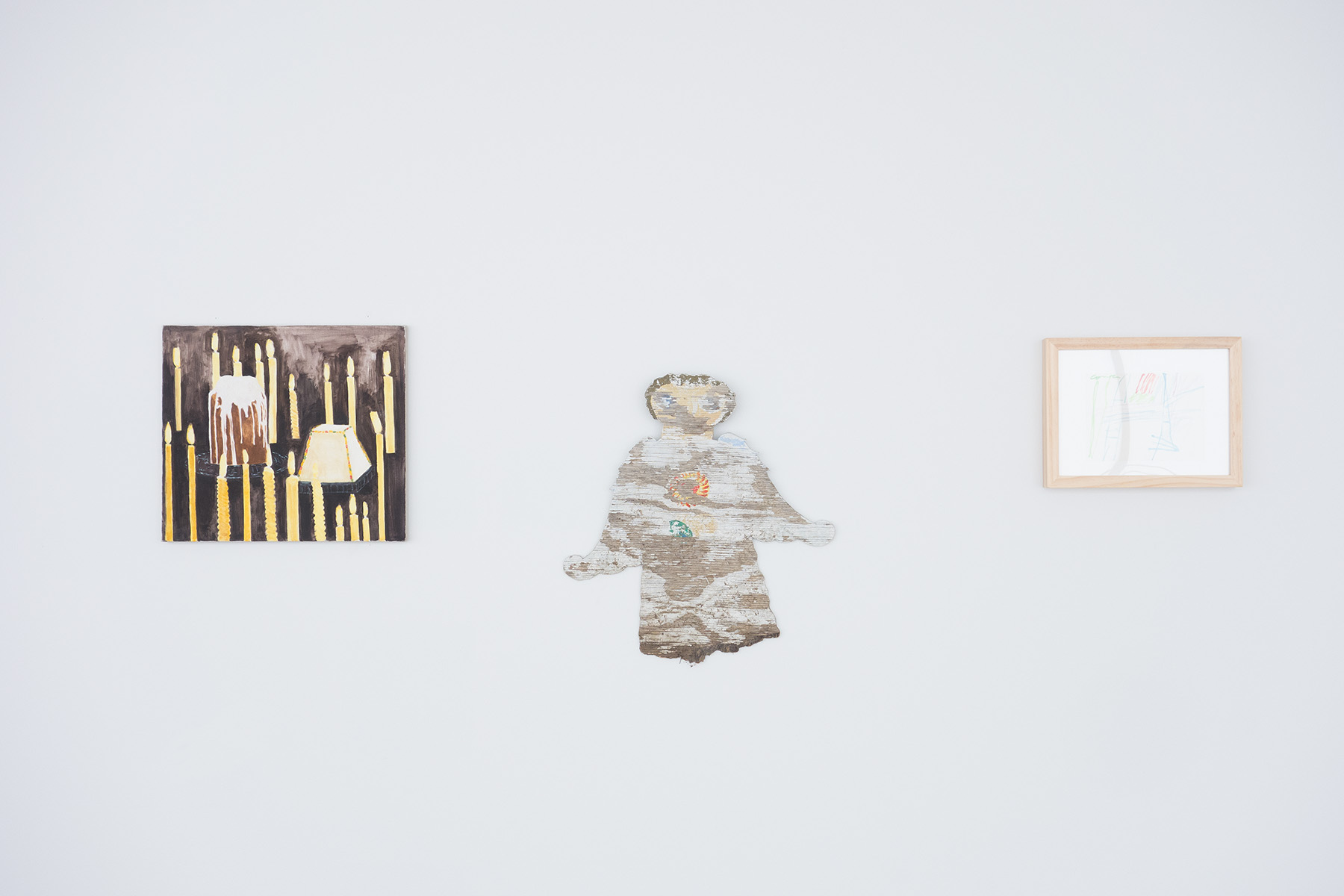

Installation view. Courtesy the artist + Mackey Apartments, Los Angeles.

So the Pueblo show came out of my interest in religion and spirituality as political practices and disciplines that have to do with the body and the mind. I had found these extraordinary works by the artist and monk Etienne Van Doorslaer at a friend’s parents’ home. From there I started to see religious themes in many people’s work around me, for example Veronica Gelbaum’s conceptual painting practice. She was making all these paintings with ‘putti’ – a very important figure. In classical painting it would embody secret meanings and values, which were corollary to the main scene but perhaps even more important. I wanted to reconnect to the research I had done for my university thesis on the sacred origins of the american city as an enquiry into the birth of capitalism and how that world order is based on the elimination of religion; its ethical dimension replaced by the koine of trade and immaterial value exchanges. LA was named after a Madonna so it seemed appropriate to do such a show here.

The Calabasas research, which Octave put together in a text we presented in the last Open House, was an inquiry in the opposite direction: we looked at the historical role of artists in processes of gentrification: from Schindler to the Kardashians.

**It’s interesting to think, perhaps in the same way as Situationism marked an awareness of architecture as a psychogeographical mapping of power dynamics, that the visible spillover of the online world into analogue space has reasserted this discourse, with the added element of where architecture and psychology, digital infrastructures and spirituality, converge. Did you see a similar kind of shift/change?

AB: Situationism is the internet. We need to elaborate a new counter model because all the utopias of the 60s, which inspired the disruptive and idealistic birth of the internet are now the total dystopia we live everyday.**

åyr were architects-in-residence at Los Angeles’ MAK Center from July 7 to September 14, 2017.