“What is translanguaging: is it the very question of language or the combination of gesture, figure, and sense circulating in and around it?” asks Jonathan Miles in a text written for Ella McCartney‘s solo exhibition To Act To Know To Be at London’s Lychee One gallery, which ran from March 10 to 17, 2017.

The London-based artist presented new work made during a Leverhulme funded residency in the Department of Applied Linguistics and Communication at Birkbeck College, University of London and in collaboration with Professor Zhu Hua.

In an exploration of “gesture, process and translation,” the work is embedded in the research of ‘translanguaging,’ a re-imagining of the meaning-making process that Miles describes as “moving over, sinking beneath, flying over, circulating around, being between, falling away, reaching beyond, withdrawing from, jutting into, breaking apart, hovering around: the elsewhere of signification.”

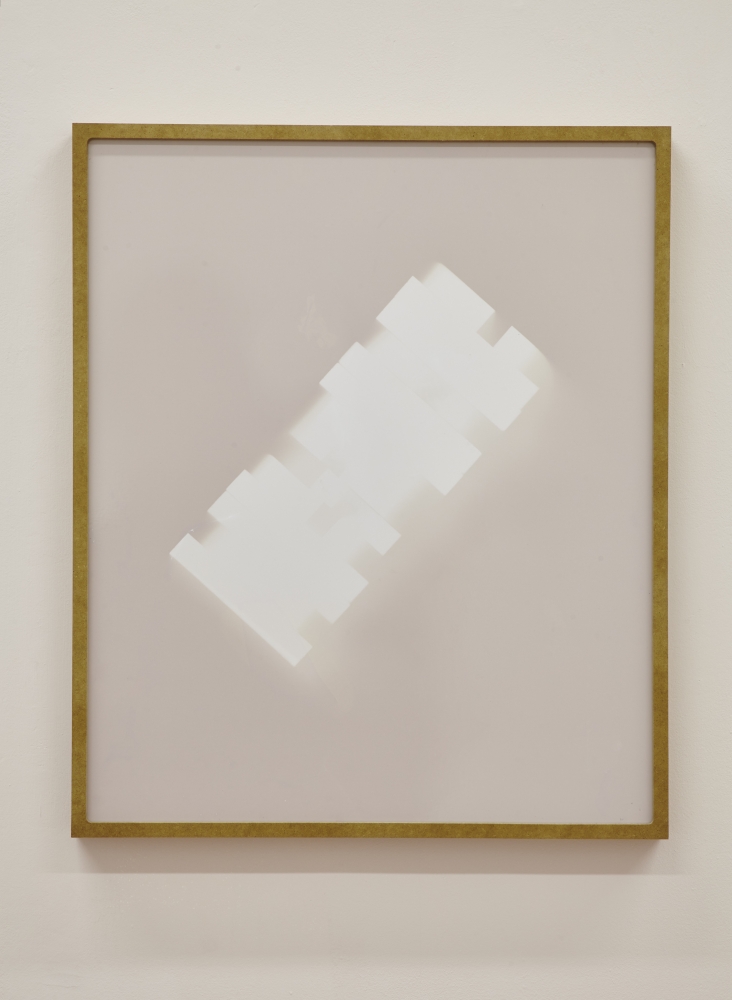

The installation included a three-hour heavy bass soundtrack produced by McCartney, Will Ward and Jack Wyllie played on a Funktion-One sound system, a vinyl floor covering, a live performance with Amy Harris and Ruby Embley, two large charcoal and soap sculptures, a chemigram, two four-sided wall based images on hinge frames and a collection of writing. As you enter the room, a strong menthol scent fills the space, which London-based writer Alice Hattrick has responded to in the text Menthol Scent below.

Menthol Scent by Alice Hattrick

I used to smoke menthol cigarettes. There was something about the combination of smoke, produced by fire, and menthol, a chemical in every kind of mint that tricks your brain into thinking it’s tasting something cold, that was so appealing.

Alcohol is still the active ingredient in mouthwash but it is nearly always flavoured mint. Listerine was developed by the doctors who founded Johnson & Johnson after Jospeh Lister became the first person to conduct a surgical procedure in sterilised conditions. In the 16th century, a number of herbs were used to clean the mouth and teeth, mint but also sage and rosemary in vinegar, alongside practical solutions like wine, which replaced urine (containing ammonia) as a popular disinfectant. In the 20th century, mint became the predominant flavour of mouthwash and toothpaste because it was widely available and made the mouth cool, counteracting the fiery sensation of astringent products. When menthol binds with a particular receptor in our brains – TRPM8 – it has the same effect as exposing it to cool temperatures. It’s the menthol that makes it feel like it’s working.

There aren’t many perfumes that smell predominantly of mint, but they do exist. Aqua Allegoria Herba Fresca by Guerlain (1999) smells uber clean, like actual hygiene: mint gum, and then lemon and grass as the mint fades like a… mint? Apparently, Jean-Paul Guerlain wanted to evoke the memory of playing barefoot in the grass as a child, crushing mint leaves underfoot, which is probably why this smells like the kind of green you imagine, but have never actually experienced. This lame story reminds me of the myth of the water nymph Minthe, who, as punishment for her affair with Hades, was transformed into a small garden plant Persephone could crush underfoot. That Minthe was also sweet-smelling was meant to be some kind of consolation.

Mint features in two iconic ‘masculine’ fragrances of recent decades. Davidoff Cool Water (1988) appears to have mint in it – it’s the most prominent note according to user reviews on Fragrantica. Then again, ‘Sea Water’ – so, sewage and garbage? – comes in a close second. Gautier’s iconic Le Male (1995) is mint, lavender and bergamot. The reviews keep on about how much women love it, but I can only remember the shape of the bottle – the stripy tank top and the ring pull choker – and the adverts: buff sailor guys smouldering in the same stripes, the object made man. Tommy Girl smells of the girl version of the 90s: lemon and mint. It’s more floral than Le Male but still fresh and clean. It smells of a time before girls preferred to smell like Sensual Woods and White Chocolate Orchid. Tommy Girl doesn’t last long, like girlhood. I imagine it’s the women in their thirties who are still buying it now.

My hands are mint and bergamot. My teeth, everyone’s teeth, are cool mint with cooling crystals. Skin is lavender. The bathroom sink is ‘lemon citrus,’ a mixture of limonene, the aroma chemical that lends products their citrus smell, with the obligatorily vague ingredient ‘perfume.’ You can’t use this particular ‘lemon citrus’ product on lino or leather but it removes 100% of dirt, whatever that means. The floor is grapefruit and eucalyptus, another plant with a scent that creates a cooling sensation, which is often combined with menthol – Vicks VapoRub is camphor, eucalyptus and menthol. The ingredients list for this product also includes limonene – it’s in everything, including the perfumes listed above – and ‘parfum’ because it is from the posh supermarket. These scents communicate with me. They aren’t meant to last, like incense, or, indeed, cigarette smoke. As they linger on my skin or in the air, the scent of mint and lemon and eucalyptus and lavender make me believe that I am not special, but, for a fleeting moment, I am clean.**