Cédric Fargues‘ Bébéfleurs is an exhibition about birth. Running at Paris’ New Galerie, from September 9 to October 13, its theme of the transformation and eventual transfiguration of humanized flowers draws heavily on the work of French poet and metaphysician Jean Phaure, his Le cycle de l’humanité adamique (‘The Cycle of Adamic Humanity’), in particular. Phaure wrote mainly about the esoteric roots of Christianity and symbolism in religious architecture. For this exhibition, Fargues produces a narrative that interweaves this esoterism with Facebook collages and edible sculptures, thus creating a universe for his creatures: the bébéfleurs.

In the past, Fargues has worked with anthropomorphised everyday objects, like vacuum cleaners, hay bales and ribbons, placing them in narratives that alternate between the esoteric and the quotidian. The artist’s use of familiar objects and actions can also be read through previously exhibited culinary experiments, such as his hand-shaped, jam-filled ‘Stigmateye Cookies’, or delicate flower-adorned biscuits. In his Bébéfleurs exhibition, the everyday is intertwined with the extraordinary, creating a cyclical circuit that can be loosely divided into three phases over three rooms; birth and beginnings, transformation through the olfactory, and rebirth through death.

On the ground floor, Fargues presents 55 collages of bébéfleurs: photos of plants altered by a Facebook feature that lets you edit and add stickers over them. Initially, the artist presented these images on social media, namely the aforementioned networking service and Instagram. The identically-sized, wooden-framed collages are hung on the walls of New Galerie’s first room. Their strength lies perhaps in an almost obsessive repetition, creating a kind of fence that demarcates the space. In the centre of the room lies a raised gardening box that takes both the form and the protective function of a greenhouse. The container houses pots filled with a mixture of crumbled cookies and leaves made of sugar paste. These form the first cycle; birth, the beginning. These three-dimensional, potted bébéfleurs flank a sugar paste sculpture of a newborn, entitled ‘Christcake’ and lingering between the camp, the kitsch and the ornate.

The first room on the lower floor hosts a presentation of thirty different oils. Working with perfumer Angelo Orazio Pregoni, these coloured liquids are distilled and liquified sandalwood, bay leaf and herbs, among others. The press release describes them as “condensation of the bébéfleurs’ vital force”. The room is empty save for these small bottles, presented on an elevated stand, behind them, a nursery-like print of a human-like baby flower standing between an Alpha and Omega symbol — the first and last letters in the Greek Alphabet — as well as Christ-centred, Christian symbolism.

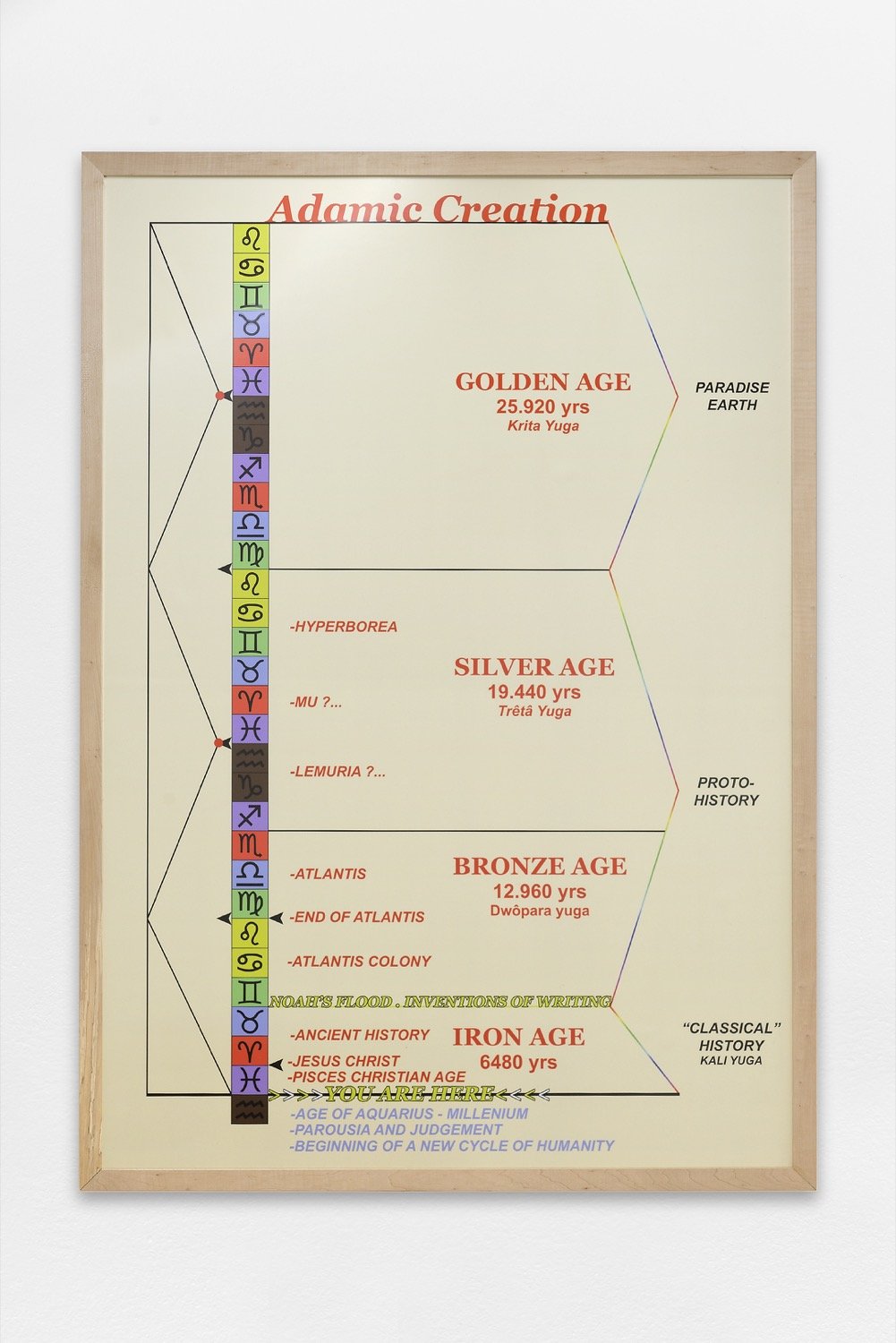

In the second room on the lower floor, a number of small pots are placed on wooden benches. Two posters hang on a well on opposite sides of the room. The small sprouting plants mark the end and the beginning of a new cycle. This is also illustrated in one of the posters, directly sourced from Phaure’s diagrams, portraying the Adamic cycle, a prophetic period presumed to have begun around 6,000 years ago. The depiction illustrates different ages or periods, ranked below each other chronologically; the Golden Age — also known as Paradise Earth — the Silver Age, the Bronze Age and, at the very bottom, the Iron Age, which Fargues identifies as the present by writing “You are here”. It mimics the repetition that can also be found in the generation and decay of nature, but in this case, they’re activated as symbols marking and predicting the end of days.

By giving animistic qualities to plants and transforming them from flat social media images into these bébéfleurs, Fargues opens up a discourse that challenges our views of perception. We accept that inanimate objects have their own design, that they are operated and activated by the contexts in which they thrive. The issue becomes more complicated when these same inanimate objects become animated. When we see a caricature version of our reality, we are forced to question what distinguishes us from these objects, or in this case, plants that are so close to being human, yet so far.**

Exhibition photos, top right.