“Please recognize your death is coming and cultivate love towards everyone you know”, says Steve Roggenbuck, self-described “optimistic shithead who loves the sky”. Currently on the move between cities on a poetry tour, the prolific maker and speaker is communicating with me via G-chat. He’s a poet and video artist harnessing the space of online, reaching thousands of viewers through his YouTube channel and social media presence. A producer of videos, podcasts, self-published books and avid performer at live events, he also founded the poetry press Boost House.

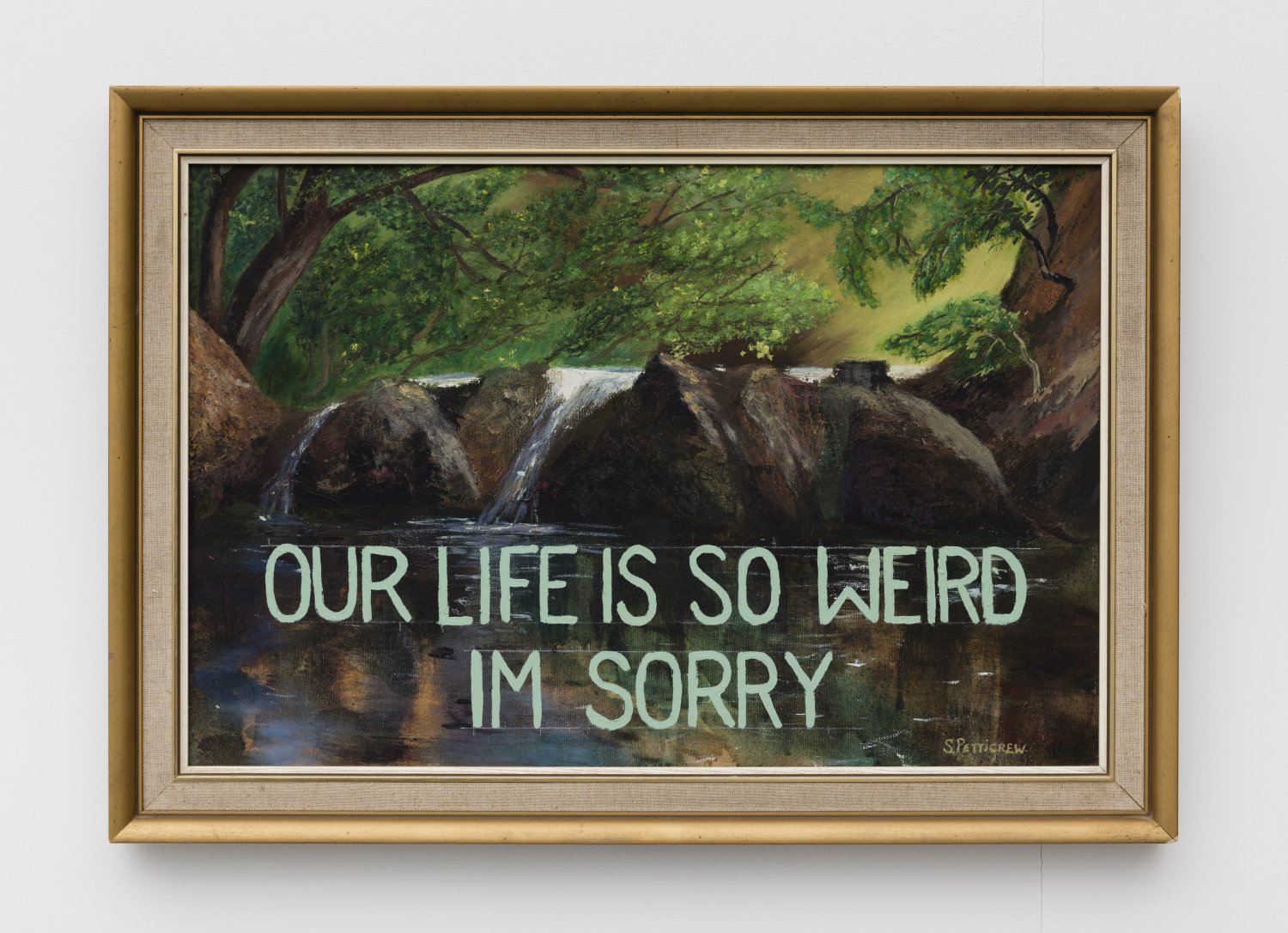

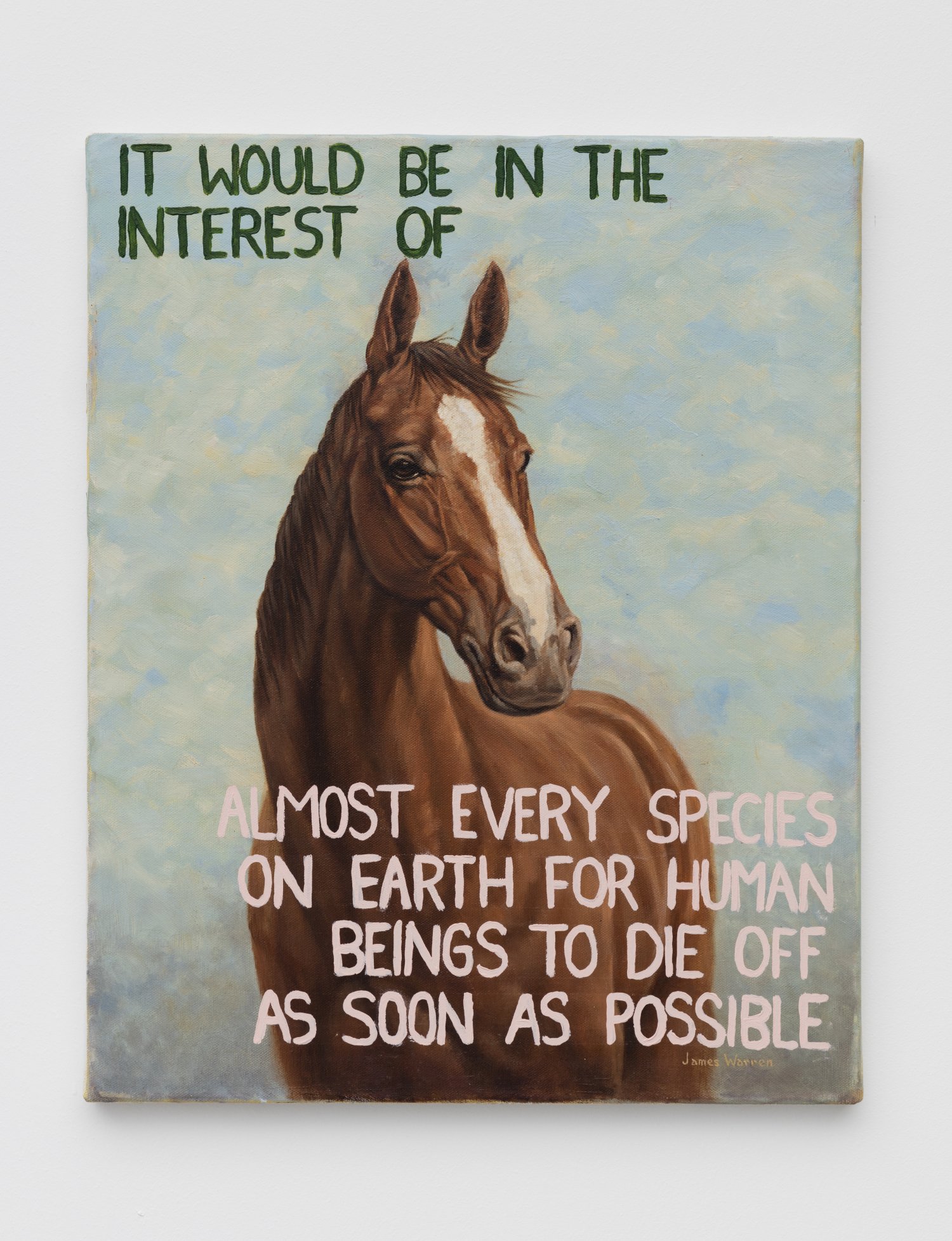

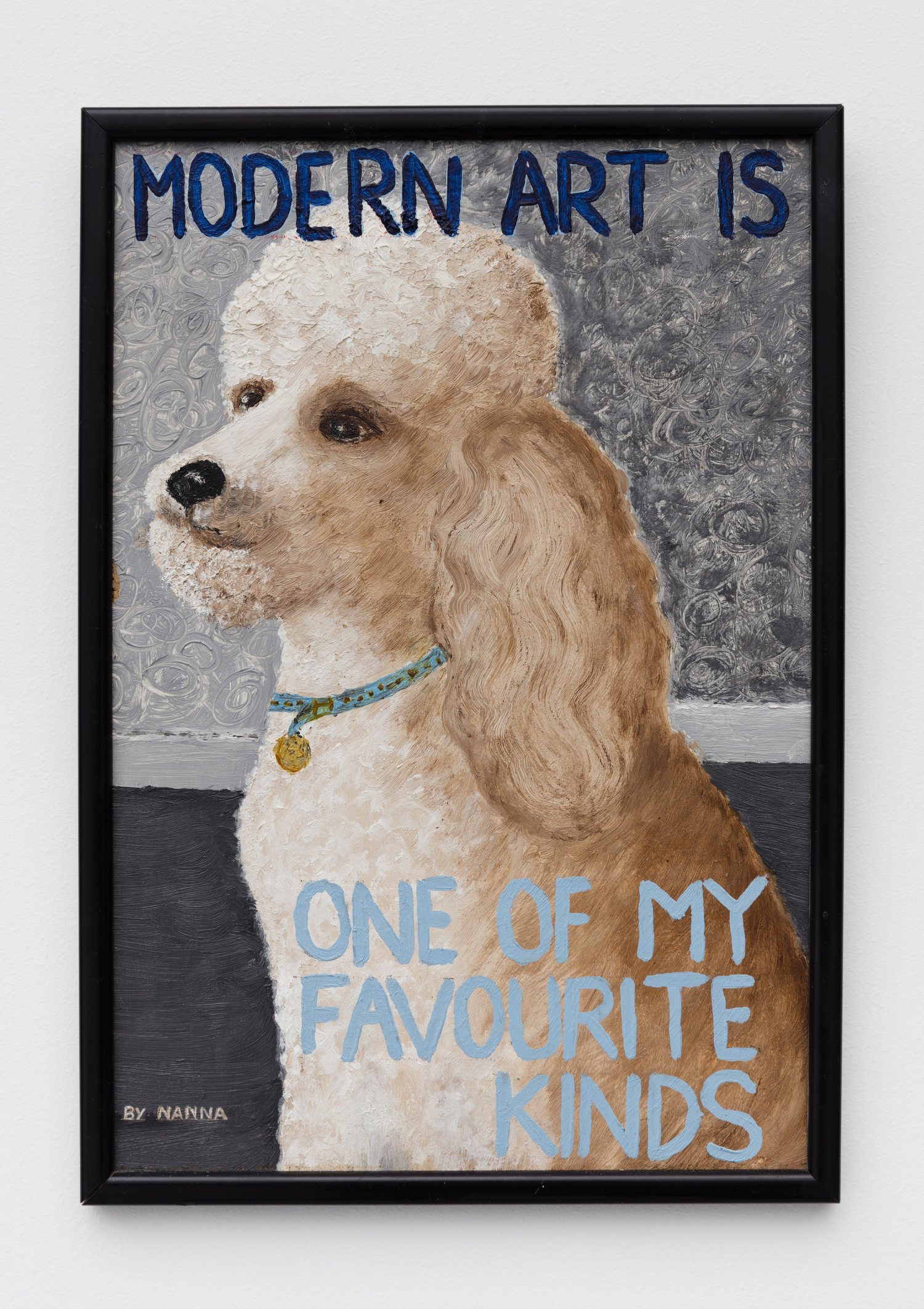

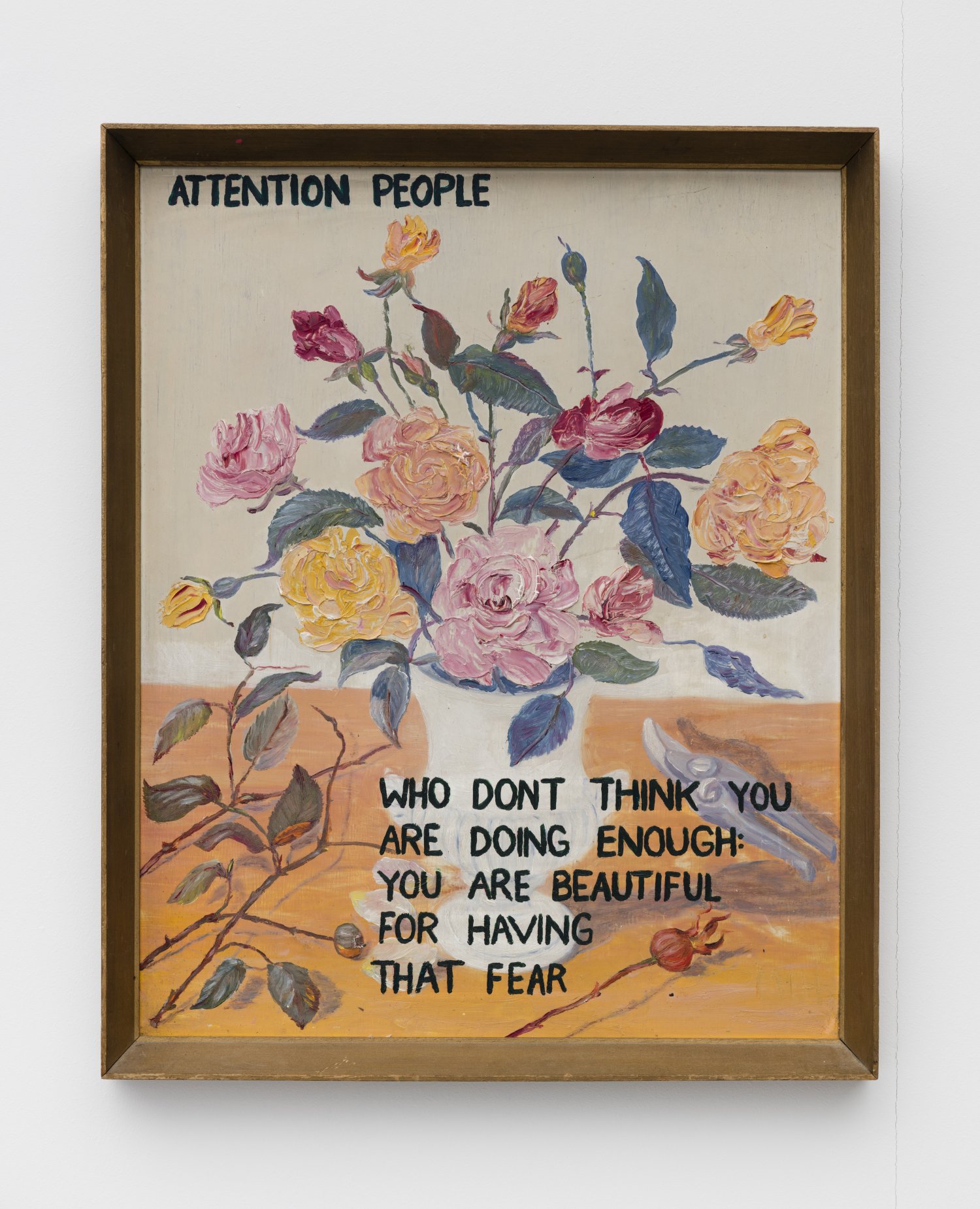

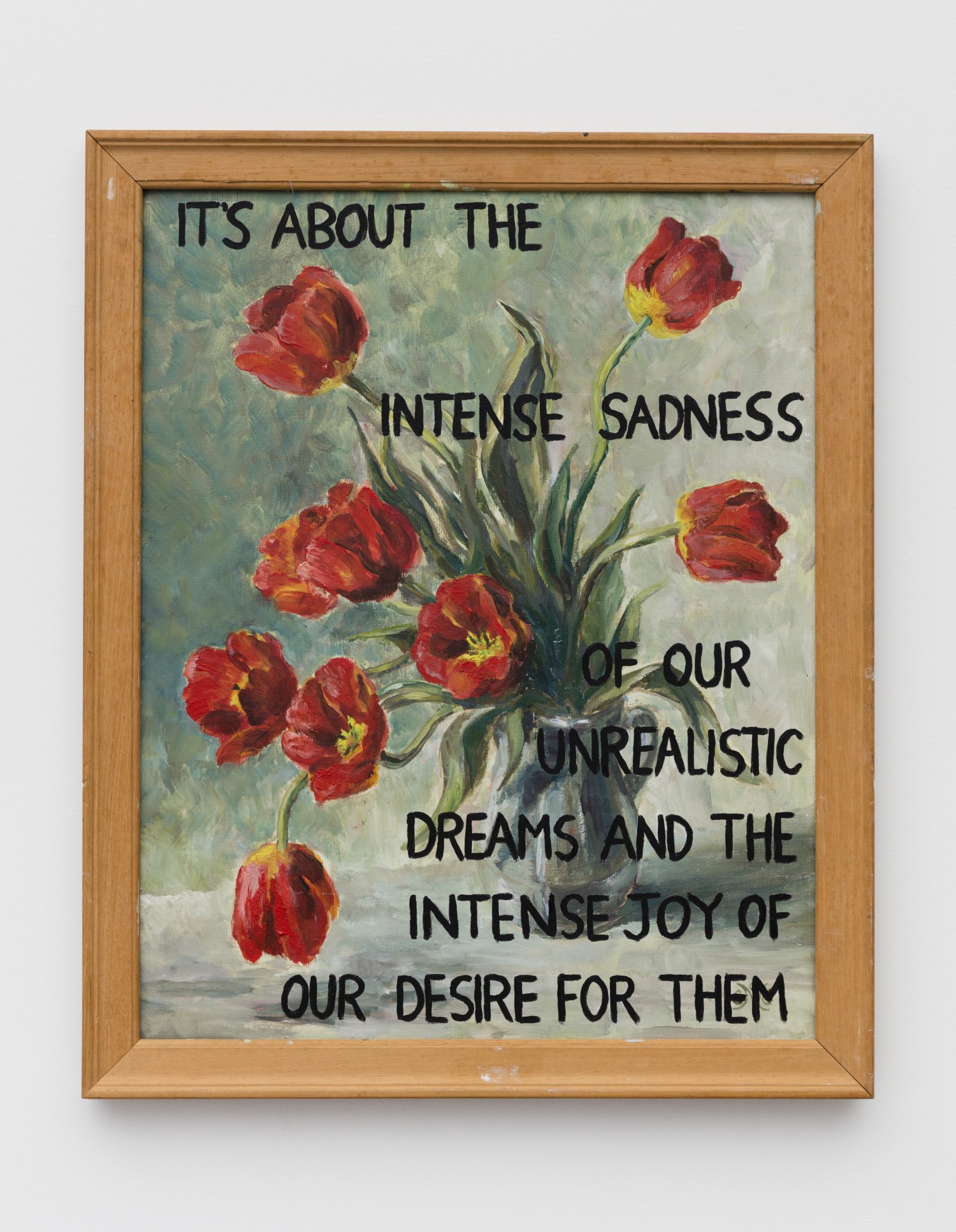

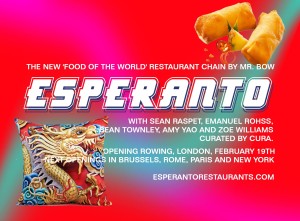

The Tucson-based personality has more recently made appearances on the London art scene. This year he was invited to perform at Whitechapel Gallery in September, while also taking part in a two-person exhibition with artist Andy Holden called WHEN YOU INSTAGRAM MY DEAD BODY, USE WALDEN BUT TAG IT #NOFILTER running at Rowing from September 2 to November 5. Coming from a poetry background, this is one of the few times he’s put his work in an art gallery but the type of audience is irrelevant. Accessible and immediate, he attracts a multi-directional crowd responsive to his un-laboured work that moves with ease and humour between seemingly unrelated content. From birds, to patriarchy, to horses; self-help affirmations to satan and appropriations from the internet, we are stirred between laughter, existential realizations and self-reflection.

During his poetry MFA at Columbia College Chicago, Roggenbuck became increasingly disillusioned with the constraints placed upon the genre, ending up dropping out to pursue poetry his own way, speaking his truths and building a large devoted following along the way. An artist who actually wants to talk to his fans, his personality not only reaches people in the palm of their hands but also IRL where he goes on tour nationally and internationally. He’s made his way mostly by bus across all 50 states of the United States, as well as cities across Canada, Norway, Germany, Sweden, the UK, Denmark, Switzerland, Mexico and, right now, Australia. Sleeping on people’s couches, selling books and t-shirts, using crowd funding website Patreon, and living out of a closet are just some of the ways Roggenbuck has managed to support himself on the cheap, and devote all his time to making.

Editing is a large part of the artist’s process: whittling down hours of footage and deleting anything that “gets boring or starts to feel slow”, the final work is squeezed into a heightened state of emotion. He’s influenced by other successful YouTubers, bloggers and self-made creatives, like rapper Lil B the Based God, who instrumentalize the web for its far-reaching potential. Within this framework, Roggenbuck harnesses similar tools that are often employed for commercial gain, while simultaneously undermining their inherent capitalist narrative. The work, politically charged, yet playful, becomes a balancing act between integrity and popularity, where he carves out a space to explore both the magical rareness of being alive, as well as the reality of injustice. Excited by the human potential for affecting one another for the better, the mechanics of kindness and a concept he calls ‘BOOSTING’, Roggenbuck offers up an alternative form of criticism. It’s one that moves into a more active version of itself, driven by its greater message: “don’t be limited”.

Your work really feels like I’m watching someone who’s had a near-death experience, or come back from the dead or whatever; basically someone who wants to wake us up. Was there a moment in your life that influenced this language of urgency?

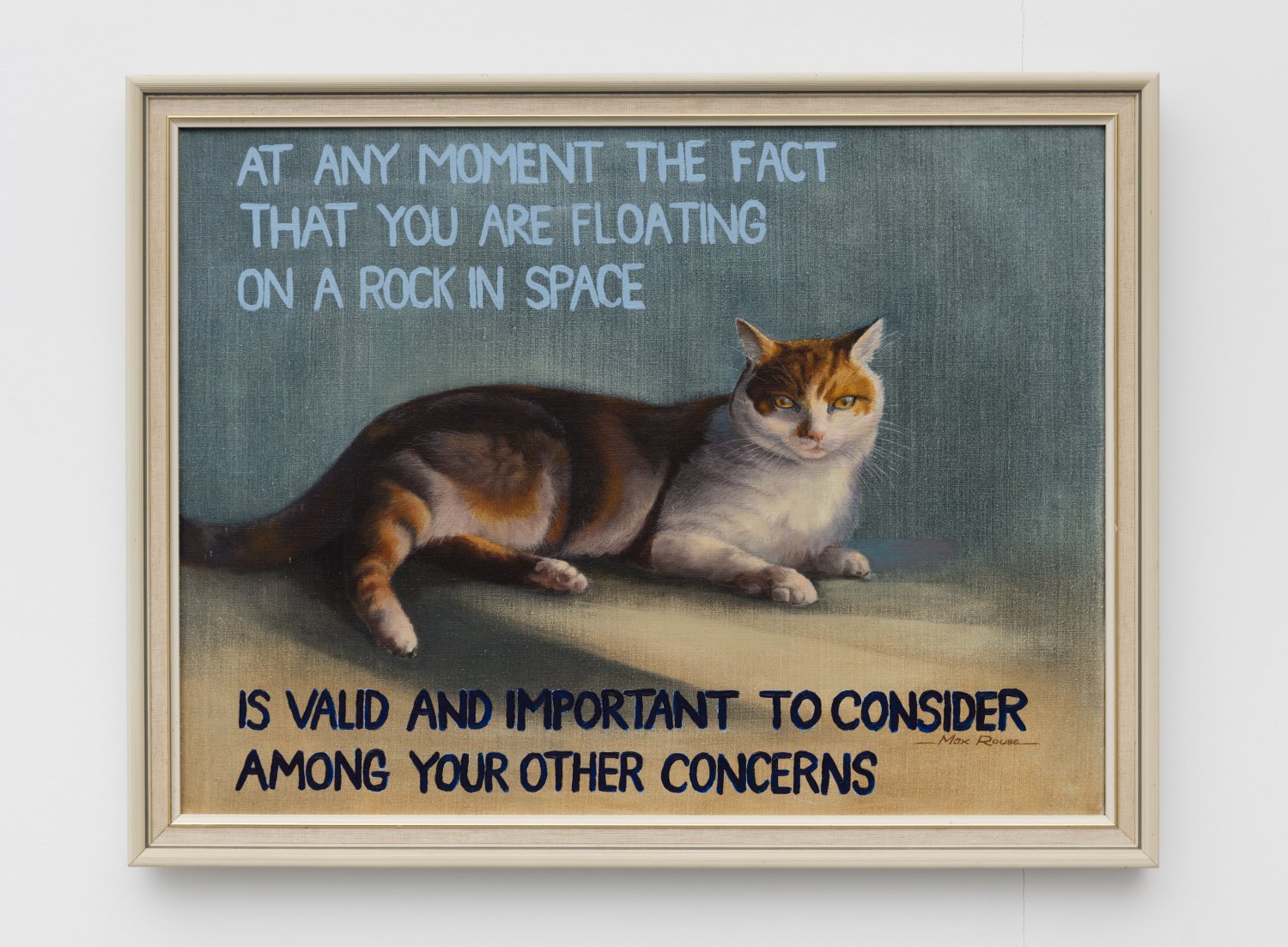

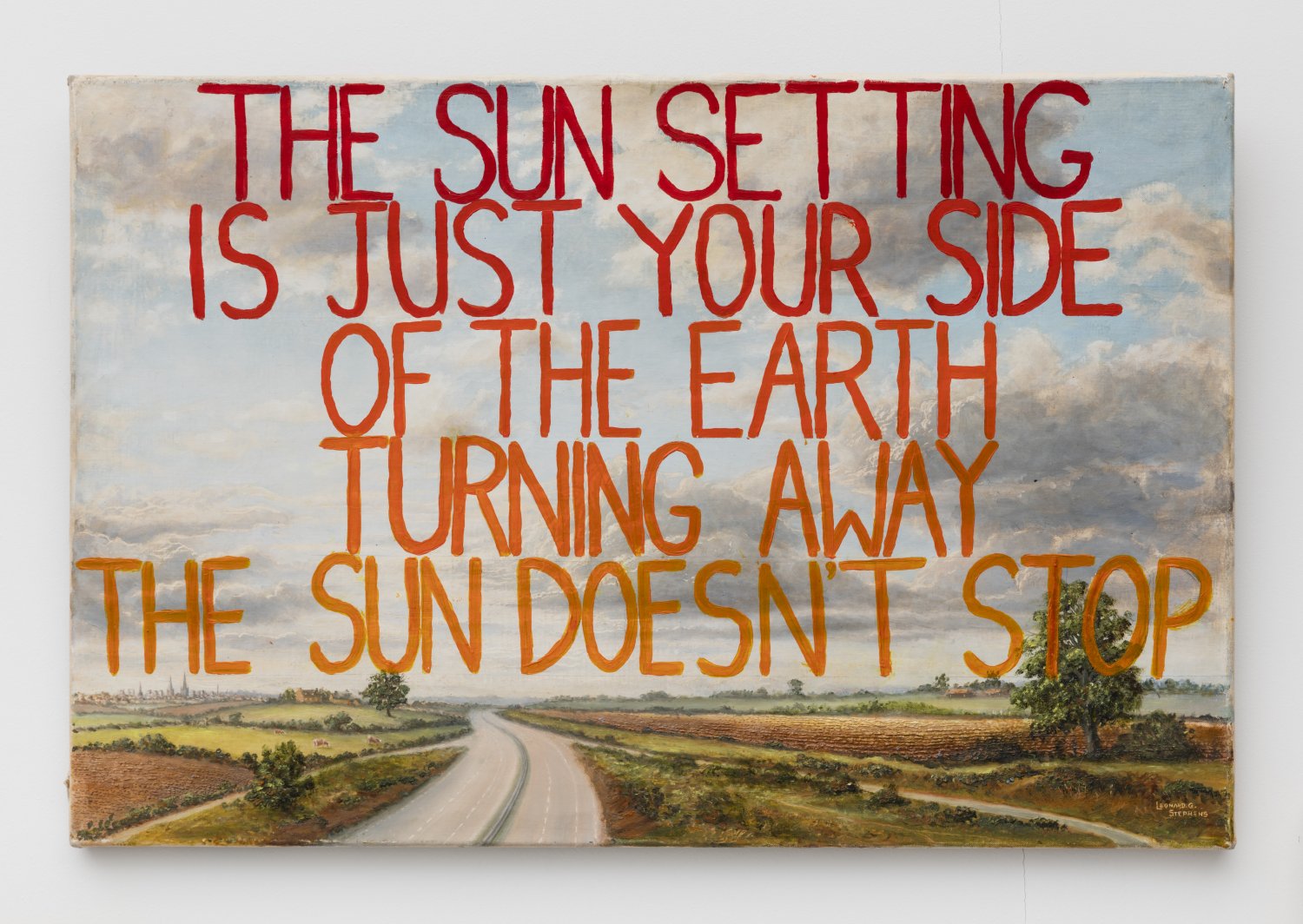

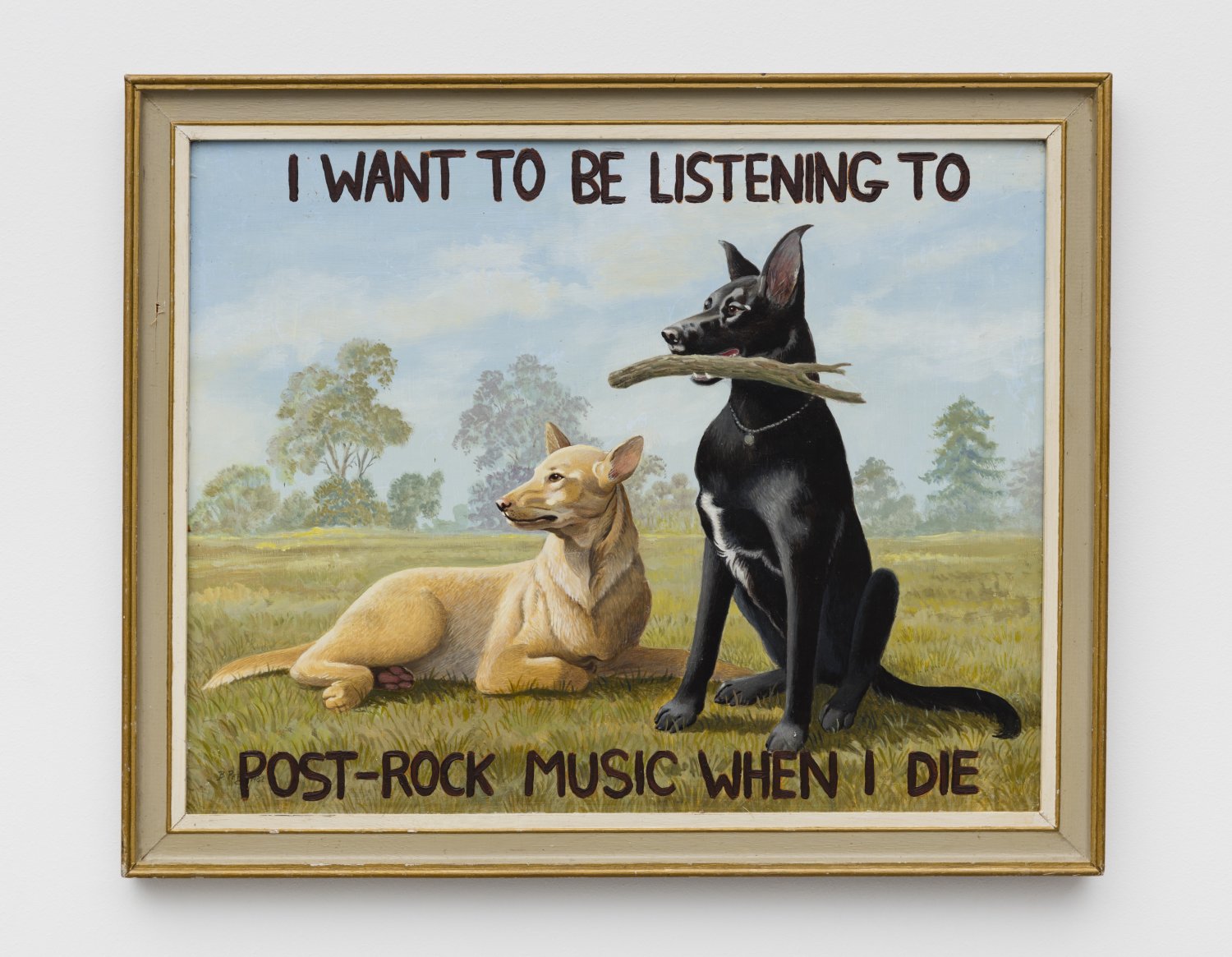

Steve Roggenbuck: I think it’s something that keeps happening — having these moments of like, ‘oh shit, I’m not doing what I need to be doing, I WILL BE GONE’. One of the memorable first times it happened was after i read Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman (the 1855 edition). I finished the book at two am, and I felt this urge to go outside, and I just went and stood in the street. I felt like Walt confronted the basic fact of being alive more directly than most people usually do, and I think at that moment I did feel more ‘alive’, or aware of the context of my life than I’d ever felt previously. But this keeps happening. Often it’s late at night, or at twilight outdoors, often i’m listening to post-rock music lol. Sometimes it’s when I’m learning about my body or the world, reading about biology or astronomy. I try to dig deeper into those moments and hold onto it and create something, usually writing or video, so I can take pieces of what that feels like and what it’s able to teach me, and preserve it or amplify it, and ultimately spread it to other people, because I think it’s a really valuable thing to feel.

They really do re-incarnate that ‘omg’ feeling. It’s really refreshing considering a lot of contemporary work has an underlying tone of a dystopia, or apocalyptic attitudes. You have this incredible thirst for the present moment, the potential for it to affect change, and to start now. It’s really optimistic, is positivity political for you?

SR: ‘Positivity’ is a really loaded and tricky subject, I’ve found. For many people, it mostly carries associations of fake cheeriness, cheesy motivational speakers, and even gets associated with corporate culture, like employees being told to smile at customers and say ‘Have a nice day!’, even when they don’t feel it. So there’s a lot of people who have these associations with ‘positivity’, maybe even understanding it as political in a bad way; people think expressions of happiness are necessarily accepting or supporting the status quo.

There’s a sense that so much is fucked up with the world, happiness in this context is problematic. I understand that. But I’ve also known certain activists who, for example, have carried such a playful energy to meetings and demonstrations, it really spread to others in the group and helped sustain everyone. I think criticism of the status quo is vital, but I think combining that criticism with an “optimism” that we can actually change things, and with an energy of “let’s actually DO this”— that’s often even more powerful. Feelings of being overwhelmed can stop people from acting. The ruling class wants you to feel hopeless! They don’t want you to feel empowered to believe you can actually change things. So in those cases I do believe optimism can be political, in a very valuable way.

Also, I think there are some specific ways in which even just messages about appreciating the world can be very politically valuable, especially if any of these are the case: (1) if the wonder and appreciation are focused on stuff like the sky or the existence of human life itself, which can’t be sold, and which is accessible to pretty much everyone; (2) if the appreciation is focused on something shared exclusively by a marginalized group, like appreciation of queer love, femininity, or blackness; (3) if the audience for the message is mostly people who are already critical of the political status quo, and the feelings of wonder and appreciation help sustain their spirit, so they do not fall into hopeless overwhelm while fighting for a better world.

Yeah, I think optimism helps combat the negative urge and ease of becoming nihilistic — which is ultimately a space of privilege, in my opinion. You manage to offer something profound while at the same time being a total goofball. It seems like you take humour pretty seriously as a tool for activism?

SR: Yeah, I think humour can be so, so valuable. You can be so deep in your sad mind, and then something funny comes along, and it can often actually pull you out of that, at least for a moment, by making you laugh or smile. It changes your physiology. And I think that function of art (to make people laugh) is underrated. In my poetry MFA program, it was made clear that my goofy joke poems were not very valuable or interesting to my instructors; they wanted work that explored pain, or explored something more subtle than jokes, anyhow.

One time, I submitted a poem that was basically a short written-out joke, and the professor’s comment was, ‘beware of crowd pleasers’. There is almost a sense in which establishment poets are trying to be boring? Maybe in contrast to that, I try to really, really value my reader’s or viewer’s time. I feel so, so lucky to have three minutes of your time and attention when you decide to watch a video I made. I want to make you laugh so much, and plant some good vibes or sustaining thoughts in there that are going to carry into the rest of your day or week too. I almost think of my art practice as service in that way. I do feel like there’s a certain type of person I’m trying to serve with my work.

It’s interesting to think of art in general as a service, and I’d agree that yours seems invested in that — especially as there’s this spiritual, self-help aspect to them. How do you separate the sort of sporting themes of bravery, commitment and goal-reaching in your work with your politics of undermining the violent individualism in the capitalist narrative?

SR: I feel like I’ve had a confusing relationship with capitalist success narratives. When making my earlier work (2013 and earlier), I was much less aware of and wary of capitalist ideology specifically, so I think there were videos in that period that unintentionally promoted capitalistic perspectives on success. Since then, I have become a lot more wary of capitalist ideology and its relationship to popular conceptions of ‘motivation’, ‘success’, and the like, but I still get confused. Sometimes I don’t know which ideologies exactly are informing my goals and desires. I think for me, success is helping people. So the most meaningful feedback I get, more than any following or view numbers, and more than a write-up in any specific publication, are the emails I get from people saying that my work has positively impacted their life, and people at shows telling me that my work has impacted them.

Yeah, I’m really attracted to that desire you have to actually connect with people, and the way you post all your work for free, essentially. I enjoyed your show at Rowing, by the way, but it was definitely strange to see it in a more ‘professionalized’ context. Do you think about the context of where your work goes, or are you happy to get involved anywhere?

SR: I think the way I’ve distributed my work is largely an effect of the fact that I value my relationship with my audience more than any other kind of recognition. I remember back in 2011, I realized that certain types of institutional recognition (people writing articles about you, winning awards, etc) don’t necessarily even lead to that many people seeing your work. I realized that certain artists making webcomics or running a blog were reaching 20,000-plus people daily with their funny art (something I am still very far from achieving, and might never achieve). Meanwhile, the funny poets I loved were publishing in tiny (sometimes print-only) literary journals and small press books that reached only a few hundred people, mostly other poets. I decided I would prefer a bigger living audience over prestige or institutional respect. Another influence of mine around that time was Lil B the Based God, and he was building a career as a YouTube rapper and internet personality without any record label, and that influenced me too. I appreciated the rawness, spontaneity, and freedom that path seemed to allow, and I appreciated the direct contact between him and his supporters.

I find internet promotion of art so exciting because no single editor can tell you ‘no’. Realistically though, you can obviously pursue both institutional and internet distribution, and sometimes the internet attention has brought me opportunities in institutions. But I’ve enjoyed it happening in that order, because then the institutions are coming to you, based on what you’ve already done with full artistic freedom online. You’re not just another application in a stack trying to get their attention.**