When I go to meet Deanna Havas at London’s LD50 where here current exhibition Due Diligence is showing, the space is still set up from philosopher Nick Land’s talk that morning. All the chairs in the gallery are scattered with cigarette paraphernalia. I joke, has someone just been having one fag in each chair and moving on? She says very seriously, “yeah, it was me!”

Usually, I ask interviewees if they’ll send me whatever they’d like me to see that can’t be found on the internet; in this case, it feels somewhat like a redundant question. It’s difficult to extricate Havas’ practice from her internet presence —oftentimes, they’re one and the same. Her work spans real and irreal space, recognisable corners of the social media landscape like Pinterest and early chatrooms, patterns of internet vernacular, bot-talk, and memes that seep into the subconscious. Her poem project Actual Person, published via Social Malpractice in 2014, assembled anonymous confessions from online message boards. There’s a weird tenderness to reading through someone’s internet presence before you meet in person; the sheer volume, in this case, preventing anyone from scrolling too far into the past. When Havas cancels on me twice, I check her Twitter to make sure she hasn’t left the country yet, like maybe I would a friend.

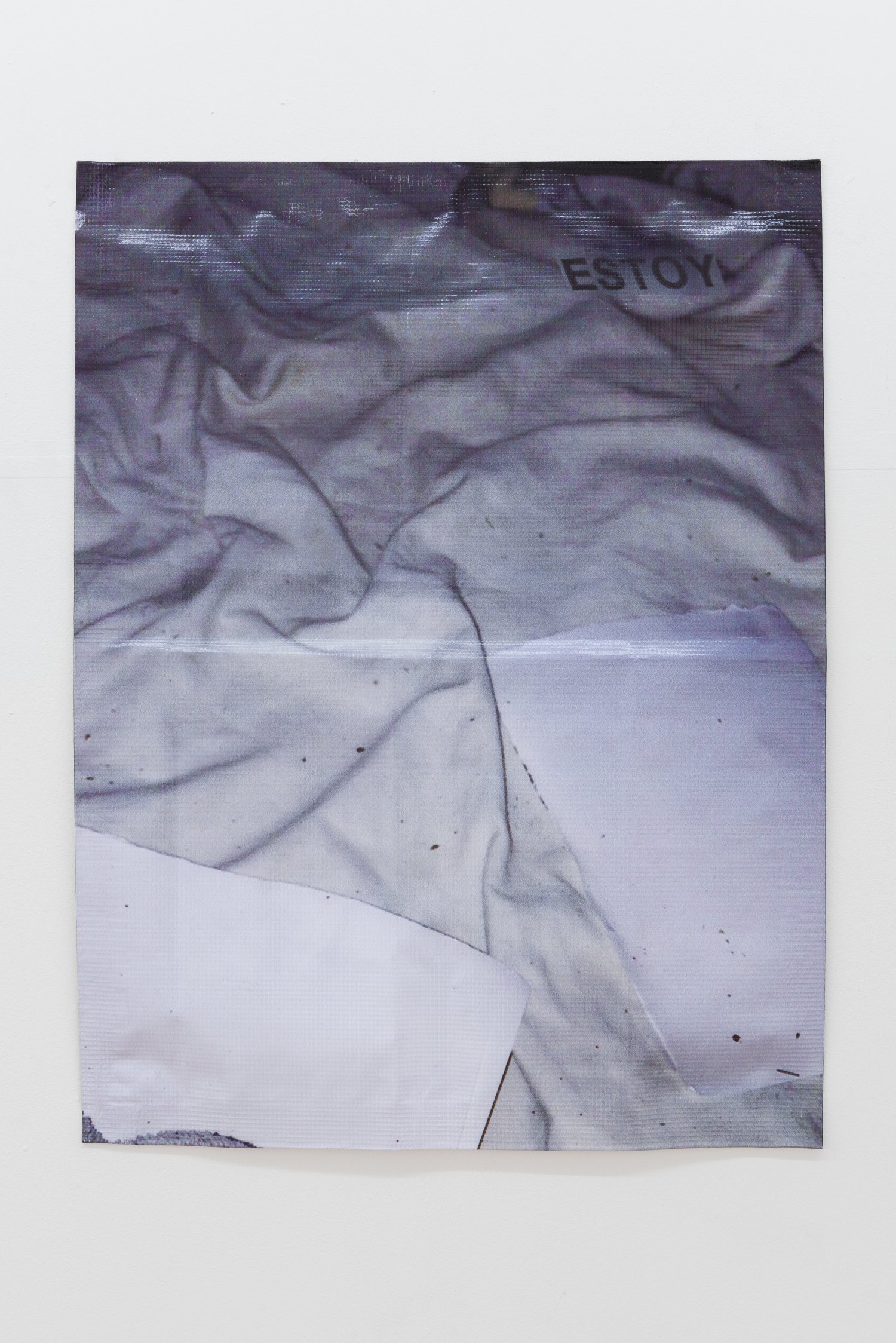

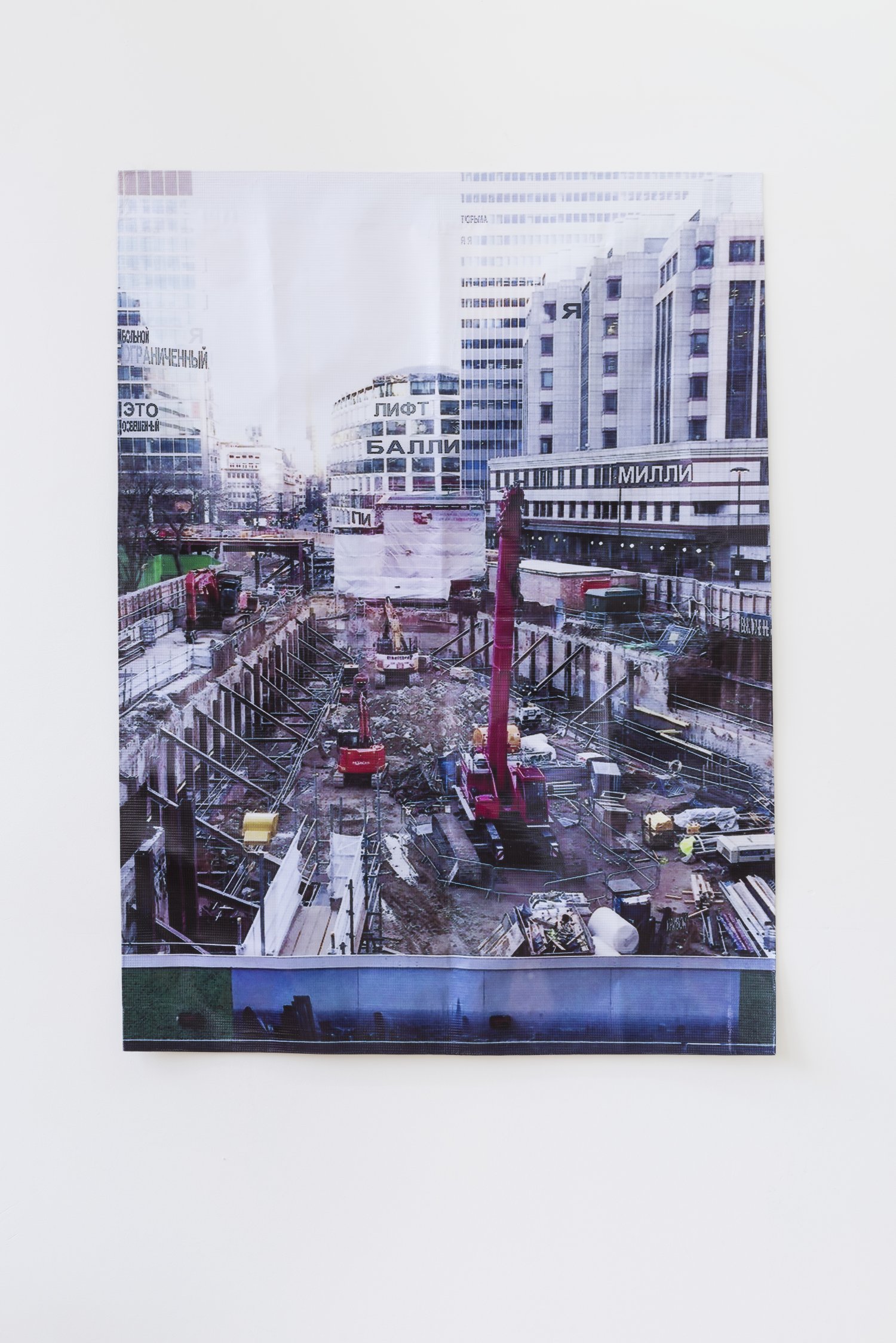

Due Diligence, running July 23 to September 3, brings together a number of bodies of work including prints of Google Translate glitches and DIY projects assembled from online blog posts. A macramé wall hanging is assembled from instructions on a Pinterest post from the Free People blog, and heat-gunned plastic comes from the blogosphere of NGO workers looking for ways to recycle trash. Everything in the room is suitcase-sized or foldable, a result of Havas’ hyperactive travel schedule as well as her commitment to shifting formats. In her 2014 work ‘Cosmic Barista’, this meant serving coffee the colour of the universe to the equally mobile superstar curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist. The crucially ironic point of this story is the part that the performance left out: that before that beige shade was announced, the scientists in charge of the project had wrongly announced a different colour, a Tumblr-ready and appropriately cosmic pale turquoise.

When our coffees are brought out, the artist is handed a rainbow Union Jack mug that she describes as “patchwork Brexit, nineties multiculturalist diversity flag, something for everyone.” Havas had arrived in London on Theresa May’s first day in office, and we agree that the shallowness of the post-Brexit dialogue mimicked the equally divisive conversation surrounding the US election. She’s conservative about the role of the artist, even as it includes performing the internet, ‘jetset poverty’ and living nowhere on purpose: “My job is really to be apolitical. I can feel one way one day, and if my mood is different another day then I can try on different ideas and ideologies, and just step out of them —and that’s fine”.

So these works seem to be around the language of the algorithm, or the hidden poetry of the algorithm, where the computer starts to read something where there’s nothing.

Deanna Havas: I’m interested in computer vision as a subjectivizing force, but I think that it just comes with being a consumer, and I think that there’s a consumerism to being an artist. So I’m interested inasmuch as its conceived of as ‘truth’. But there are so many truths out there. I like to mix it up and have different subjectivizing forces, and I do also have collaborative work, so that’s another avenue of coming to content. Lately, I’ve been interested in making painted works, so I want to pursue that for a while. I never want to stay fixed. I don’t attach myself to any political ideology too strongly and it’s the same with medium —or, not medium but way of working.

Do you think that’s a reaction to internet saturation, not necessarily just in your practice but in daily life? To desire this materials-intensive, heavy practice?

DH: I think what is important in that regard is that I see the artist as this jack-of-all-trades figure, and obviously I’ll pursue material things here and there —I studied animation, and in college I spent a lot of time in front of the computer, so it could be that I was tired of doing that and wanted to move into a more material practice. But I also do very immaterial stuff sometimes, performance, poetry. I think what’s important is that between each project the perspective and the content is very different, so in the totality of myself as an artist I’m this entrepreneurial, neoliberal subject. Which is obviously inherently political: that in the myth of the artist-genius that I do everything, or that I can do everything, or that I should do everything, which I think is true of the figure of the contemporary artist and the logical conclusion of the neoliberal subject.

Do you think that the internet is part of that performativity? Or that it’s a method of both being that neoliberal subject but also performing it in a way that is palatable, that is a persona, the persona of ‘the artist’?

DH: Definitely, I think above all it reiterates that. It’s our notion of genius that comes from centuries of philosophical ideas, and the internet definitely reinforces that. But the artist is not just a political subject, it’s also a human! Whatever that means, or an object. It’s like an entity, a myriad of entities.

And having made work that lives on the internet, is there a difference when you’re making work for a particular city? Is the work read differently in this context?

DH: Well, the internet has a very concrete object-based model anyway, so it’s really just a different type of object. A website is a context-specific object, and art objects function like that too. It’s been interesting to have these political talks going on when my work is so —not. I think that in the way that the experience of viewing them is neutral, that you can have these sorts of events in galleries. You’re not saturated with political meaning already.

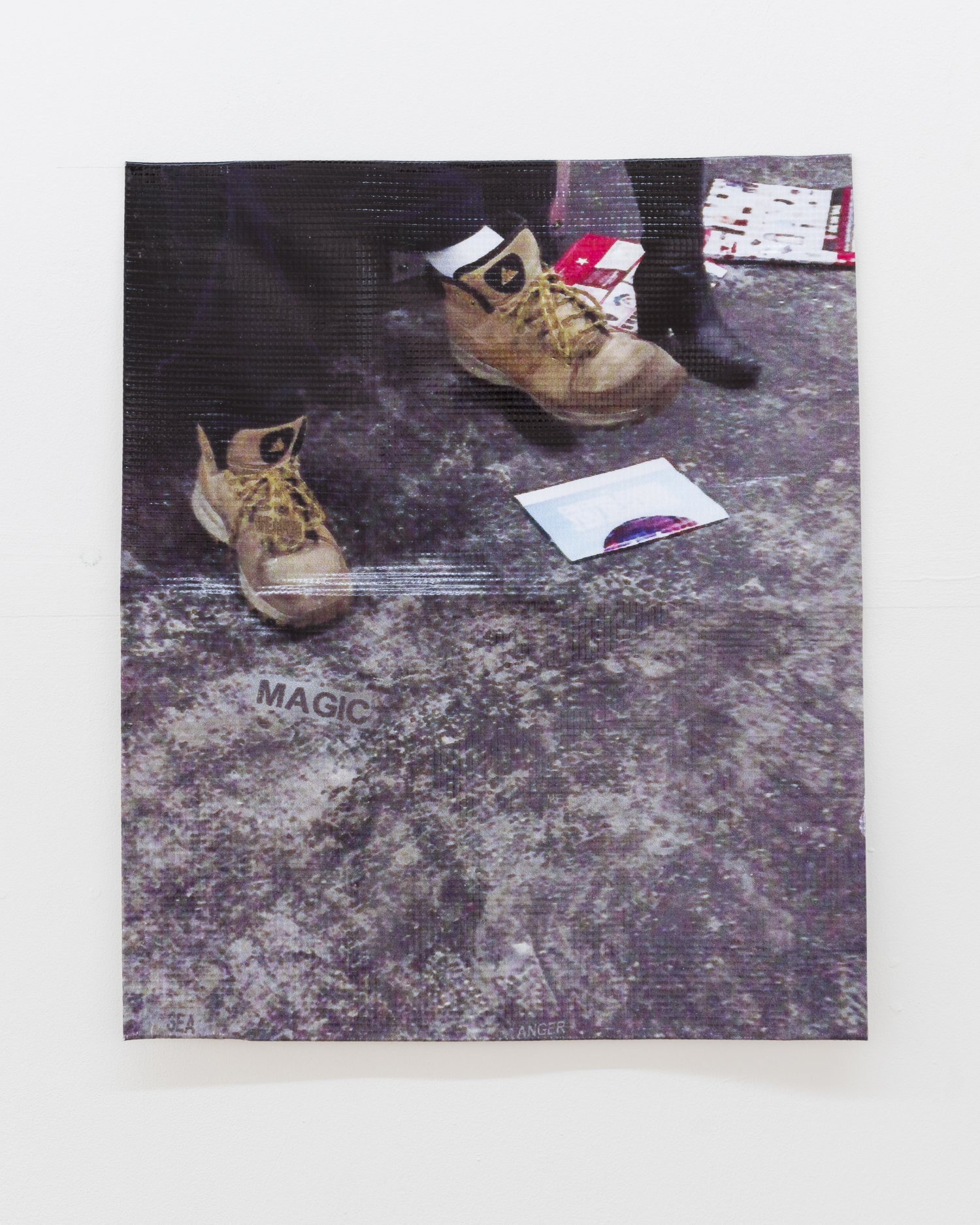

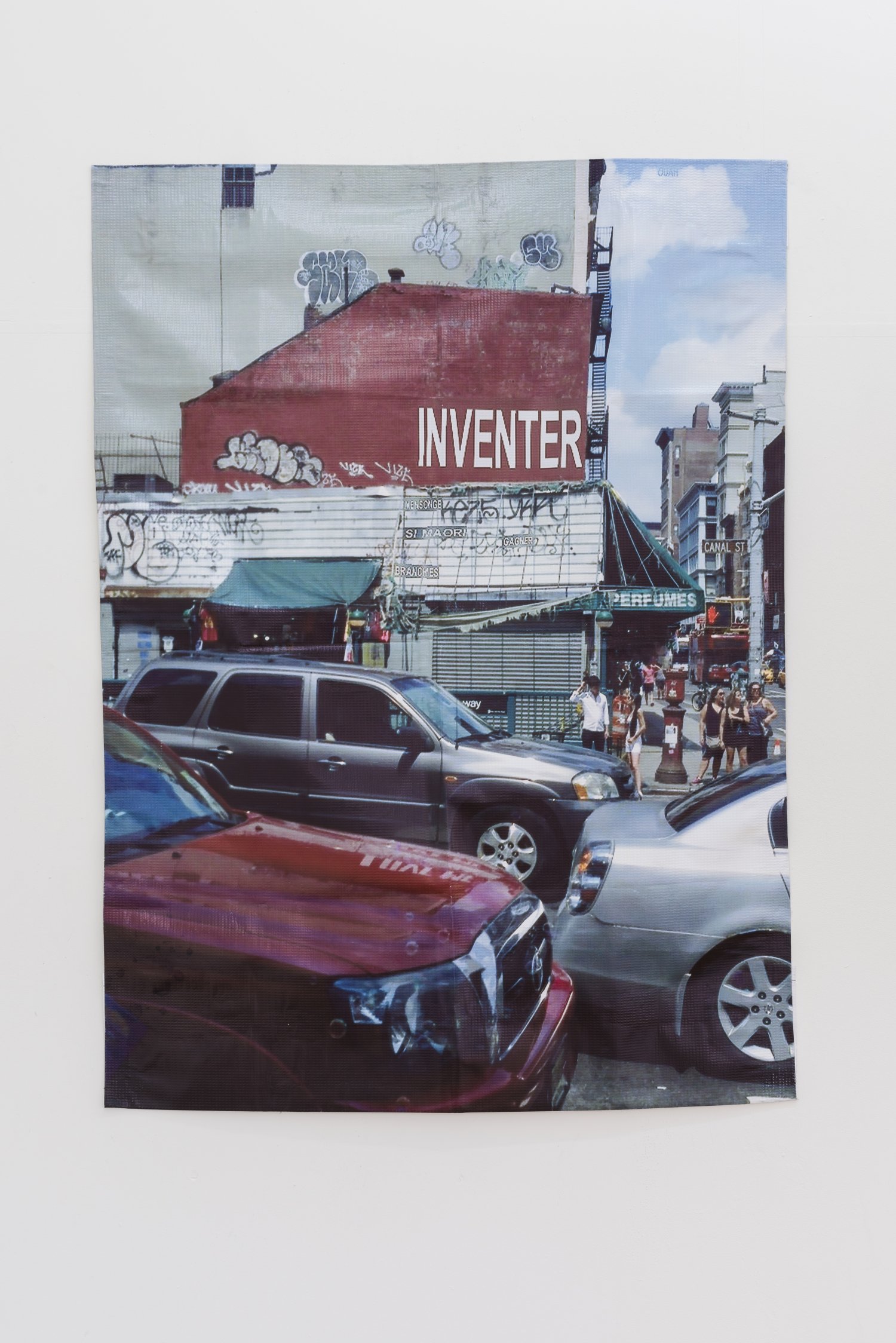

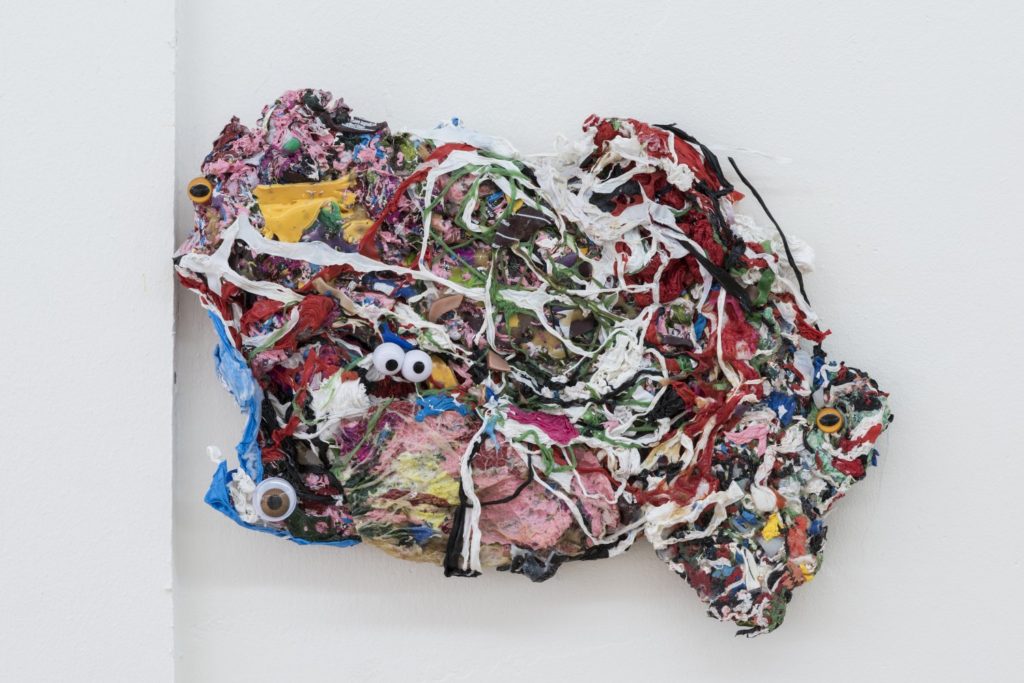

But they do get overlaid. This space feels very close to the street. Ridley Road is right there, and in the evening between the market and the garbage truck it’s the most amazing trash. You can walk there then and read it like a horoscope. These works are referring so much to the detritus of the city, it requires a certain sifting through.

DH: Yeah, and in parts of Manhattan it’s the same. To make these, I was collecting trash for a whole summer, half a year. I felt like I was living in a waste processing centre of my own making.

But that’s what being an artist is, right, the collection and transformation of these things?

DH: That’s me when I’m travelling. With my work I’m sort of trash woman carrying around my bastard children around in my suitcase! Being so conscious of stuff and its real materiality. But also ideologically, ideas of waste.

I was going to ask you about poetry, and this turn that has been happening of artist-poets —not that that’s a new thing. I wonder if it’s a question of being stressed out sometimes by materials and their constant mass, storage, weight. A poem is the most transportable object.

DH: Well, I know some artist-poets who do very well in the market and still do poetry! I think that we’re in a very romantic time now and that comes with the territory.

And aside from economic reasons, I think it’s seductive to be able to just turn up and read something from your iPhone notes. Whether or not that’s actually done well or not is another matter. You can encompass everything.

DH: I’ve seen a lot too, and it looks, like, cool and casual to just whip out your phone and read from it. It’s nonchalant.

That fake, disaffected voice.

DH: Like, ‘oh, this is just something I’m doing in between instagram and snapchat!’

In terms of travelling so much, does the work reflect that?

DH: I think it’s very important to develop a cool subjectivity to make work from, because everyone is an artist —I don’t know if that’s true or not —but I find that developing my subjectivity in order to eventually make work, that it’s important for me to have this poverty jetset lifestyle. It’s not easy, I’m literally dispersed, but I find that that is more important than my comfort. The work will be shaped by that eventually, and I think it’s more honest.

Why do you think that?

DH: It’s more crucial to the contemporary artist’s subjectivity that they be ubiquitous, the way the arts are ubiquitous. We have biennials everywhere. And though I would love to have a studio to go to, I think that maybe the studio artist is a bit antiquated? I mean, artists still have studios and they work in them but they have to travel so much. A lot of that becomes extending the individual into some sort of functioning operation that may entail getting work fabricated, or making work that fits in suitcases, or reading poetry off an iPhone. It’s definitely not so comfortable, but it’s important to crafting subjectivity and I feel that’s the way it should be.

It can be helpful in terms of problem-solving, if you’re having a show in a place that you’re not. How do you make yourself, your work, exist without your oversight. Like a poetry reading on Skype —how is your presence transferable or translatable?

DH: We were doing a lot of work with that when I was in Zurich. I was surprised how moving this format was, even though it was tele-present and not ‘live’ reading.

It functions as its own format. I did a reading to Sydney from here, and the curator carried me around the gallery beforehand! Like this head in her hands, completely bizarre.

DH: Me too! I was on an iPad once.

Yeah, and then you’re reading and they’re gathered around like you’re this bonfire.

DH: That glowing light.

With the macramé work, and the DIY tutorials from the Free People blog, I think it’s so funny because people are turning something small and useful — say, a piece of rope — into something large and ornamental. It’s learning a method, but the method is useless.

DH: Yeah, and what’s the point of all this DIY? I wanted to look at this liberal mythology, and, more importantly, the transformation of care. In their own way, all the works touch on that. This anthropomorphizing of inanimate objects, this little world. These things don’t speak but we superimpose language or faces on them and magical life is breathed into them and they assume human properties. That’s why we have this consumerist culture…

Because we love things so much!

DH: They’re all alive and human and magical, and means to an end.**