It’s probably worth noting, in the context of her current show, that Kate Sansom’s Instagram is set to private. Her exhibition, Assets, is on at London’s Rowing, running May 27 to June 25. The gallery is a white space tucked into a nice little mews near Kentish Town tube station; I arrive in the sun in a sweat. I catch Sansom as she breaks her journey –recently landed after a break in Berlin, she is flying back to Canada, where she is based, the next day. I know her Instagram is set to private because the night before we met I followed her, hoping to get a sense of what she might be like —she accepted only after the interview.

As a show, Assets is cohesive. The works are not legion, but the gallery isn’t huge so it doesn’t feel sparse. A mix of installation, film and paintings, Sansom has used the exhibition to create a narrative space through which she interrogates the visual language and social ramifications of Instagram through the imagined story of a minor-league Instagram ‘celebrity’ (or maybe ‘performer’).

Before we talk I regroup and look at the exhibition. I don’t take notes, the interview takes place in front of her work and we refer to it frequently. Sansom’s research, she tells me, developed out of her love of confessional literature, as sort-of maybe pioneered by the likes of Sylvia Plath and refined in the ‘90s by books like Chris Kraus’ I Love Dick. In the age of the performed internal life in which we now seem to live —care of social media —it feels more relevant, and important, than ever before. The parallels between a literature whose focus is the interior life and subjective experience of its author and the social media platforms that provide a 24-hour-a-day feed into the lived experience of friends, acquaintances, celebrities —or, increasingly, anyone else —are self-apparent. But the differences, in the intent of the author, or in how we consume them, are important.

Literature and social media seem to exist as almost opposing platforms; the latter offers fluidity, exchange between audience and performer but also a total absence of any sort of quality control (see: Rich Kids of Instagram, as an example). Plus, the slightly unsettling relationship between number of followers and advertising potential, which sees the integrity of some lifestyle posts called into question, if not actually totally voided —certainly, discussions about social anxiety, self-esteem and body image haven’t diminished since Instagram hit the scene. Obviously, literature also needs to turn a profit, but somehow it seems less sordid: sales affirm only that people want to read the book, it’s not ‘branding’ the ‘content’ of a ‘life.’

Sansom’s way into this very relevant and very knotty arena is through one particular Instagrammer, who has since deleted her account, called shitkicker2000. The film that forms the centre of the show casts the snapshots of life offered by shitkicker (or her imaginary counterpart) as a kind of pitch deck; the confessional social-media-documentation of a regrettable evening spent in the wrong company spun into a literal articulation of the business pitch that it has come to represent.

The film toys with professionalism and the slackerdaisical; beautifully rendered digital landscapes against shoddy hand-drawn animation, glamour offset against mall jobs. Motifs harvested from shitkicker’s account are presented alongside imagined realities as Sansom tries to fill in the blank spaces between the carefully curated, performed, and consequently utterly unreliable experiences of the Instagram personality.

The accompanying paintings further support the arching narrative of the show, while also confronting the devaluation of the currency of the image, as facilitated by Instagram. Through the use of memes as source material for considered abstract oils, Sansom challenges the disposability of images —or maybe the status of painting; either way, she interrogates value. The value of the image pre- and post-ubiquity. Plus, more broadly, the value of performed existence: the meaning, or not, of a life lived through images.

Ok, so watching the film, and looking at the relationship between the works here, there’s a strong sense of narrative; how do you use it?

Kate Sansom: Well, the project started around this one Instagram personality that I took an interest in, shitkicker2000. It was not necessarily just her but it was this general sort-of paradigm I guess, that I was noticing on Instagram. I’m a huge fan of confessional literature and I started to imagine the two as not totally unrelated in some form. Using this online social media as a sort of diary for every day. And discussing very personal details of one’s life, in this very open forum.

But then there’s also these weird mutations, or adaptations to it, where there’s all of these tropes that are constantly presented, like the selfies, memes, celebrity, celebrity photos and stuff. So, I was thinking about it as this sort of a new form, but still powerful in its expression. Or at least its potency. She has 10,000 followers for a reason, right?

I was imagining this avatar, this personality that she’s created being very plastic and professionalized. But then also having these very dark and sincere moments that come up. There’s times when there’s these photos that are insinuating that her father abuses her, or that she’s grappling with an eating disorder —stuff like that.

I was thinking that developing an online personality is much like making a presentation to really sell yourself: you’ll then get sponsors and start to gain income from it as well. So I was imagining it as a pitch deck, but then in this very anti-presentation way, of more like the confessional side. Turning it into this sort of very jolted and emotional narrative; using the format of a pitch deck, but making it instead about the morning, waking up next to someone that you don’t want to be lying next to.

Which relates; Instagram is so performative as a medium that you have these people that are simultaneously operating in a really confessional way, but the way they perform their problems also sort of fetishises them.

KS: Right, they’re sort of capitalising on these moments, on this candour.

And I guess the spectrum is whether that’s cathartic, or whether it goes to the other end and it’s in some way enabling?

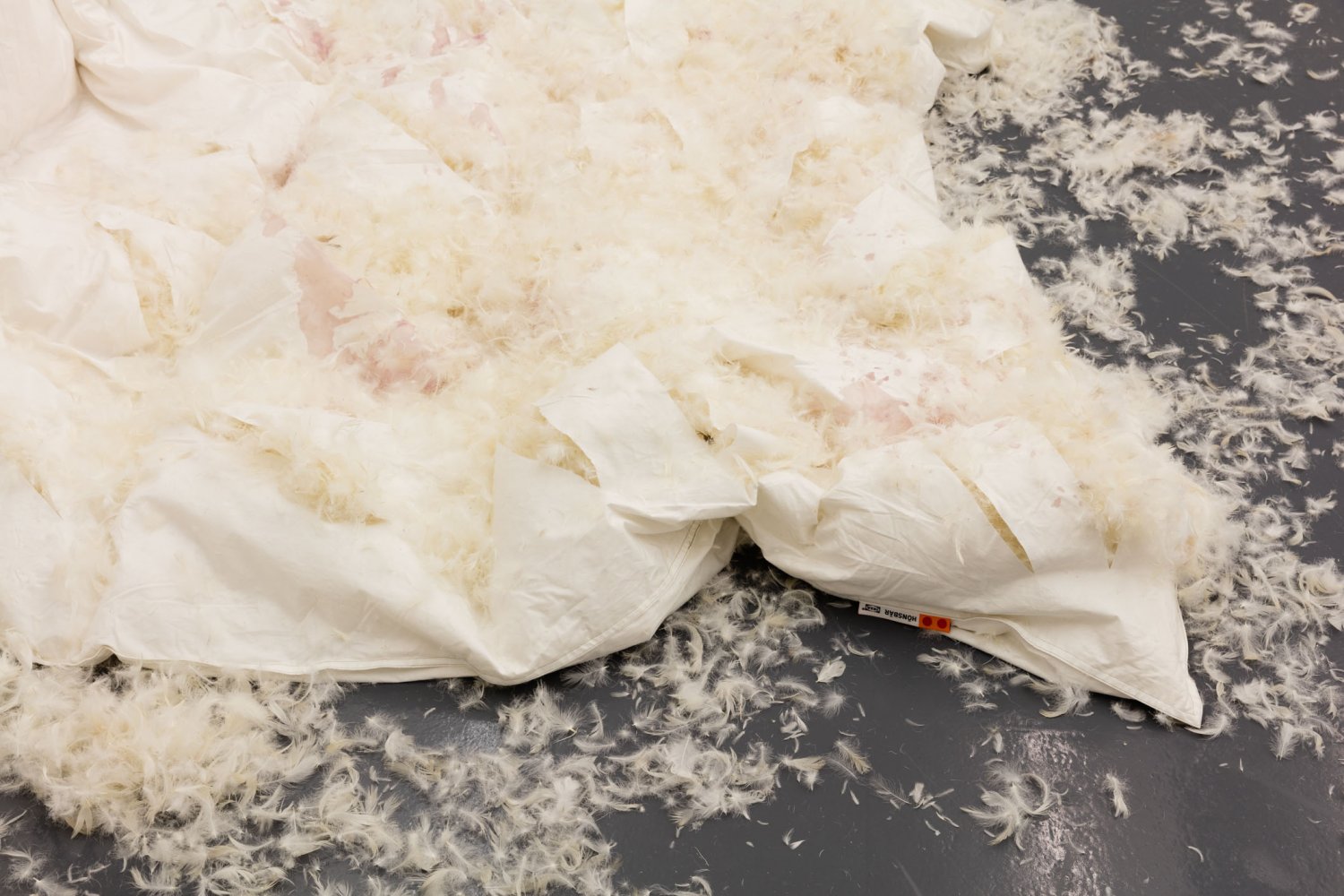

KS: That is the question, whether or not it’s like an empowerment, or whether it’s diminishing ‘the tradition’ as a whole —that’s the question. That’s a question that I don’t have an answer for. But throughout the process I was really interested in creating this sort of slippage between this online veneer and the material reality of the human that is experiencing it. I guess I sort of imagined like, a bedroom motif to go along with the narrative, but in this distorted, dystopic way.

Your work presents a tension between immaculate digitally rendered landscapes and rougher elements —a shaky, hand-drawn, animation; a slashed duvet. So within this bedroom narrative, how do you view the roles of the readymade and the things you’ve made? The digital and more analogue?

KS: There’s definitely a real slippage between digital, virtual reality and then the grimy, very real elements. I guess the easiest way for me to answer that is to admit my inspirations, or what I enjoy in artwork and where I would position myself. I’m a huge fan of pop-conceptualism, artists like Ashley Bickerton and Isa Genzken, and all of these forms that take shape, incorporating readymades to some degree; doing that with a popular moment in mind. I really wanted to create this feeling of there being an actual environment and a not-so-polished atmosphere that this person is incorporated into, is like a part of, informed by what she’s putting up online. I mean, like, the details of the work —the wine bottle, the rosé wine is like a very popular trope in a lot of her images. In the film there’s actually one Instagram image; it’s a body shot of her, holding a big glass of rosé wine.

What’s your relationship with shitkicker2000 and her material? Do you think that her performance of her life through Instagram to 10,000 people —which is presumably making her an income of some kind —legitimately puts her personality in the public domain?

KS: I knew when I set out making it that I didn’t want an intimacy with her in any way. That I felt like that would somehow remove this relationship of a fan-fiction telling. And I think I just looked at it like I wanted someone who had a pretty decent fan base of their own, but not necessarily someone that everyone would be familiar with right off the bat. And I really wanted to just use it to describe what I see as a form, or as a fairly common idea of what’s being put out there.

It was funny, I did a talk with Paul Luckraft at the Zabludowicz Collection and there was a lot of crossover in themes between the Emotional Supply Chain that he curated there, and this. And actually right after our talk, they did a panel discussion on social media and the presentation of the subjective self through social media, and what that all means in this overarching idea of subjectivity. Some really interesting ideas came up —they were definitely using confessionalism as a way of describing these people, this generation of people who are just so comfortable with full candid exposure to the details of their lives.

So with your interest in confessional practices, have you ever been tempted to participate in that way of making yourself —is it significant that you haven’t?

KS: Right, I mean, I don’t think that I necessarily straddle the world, this performative world, in the same way that they do. I certainly don’t spend my time posting enough selfies to generate the attention of an audience of 10,000. But that doesn’t mean that I have a judgement. It doesn’t mean that I stand in negative judgement on it; it’s just not the format that I choose to express myself in.

Do you think as a phenomenon it could be viewed as narcissistic?

KS: That’s the thing, I’ve never really thought about it as a reflection back on oneself. I more just thought about it like the socialized human, as this being incredibly intriguing to enough people that it’s generated categorically; a generation of people doing it.

The press release on the website touches on this idea that in the search for ‘likes’, in using that as a source of affirmation, one becomes more alienated. It highlights the absolute breakdown of meaningful connections through volume.

KS: And because of its form, and how mundane the form becomes as a result of sheer volume of people doing the same things, and presenting them in the same ways. And just Instagram itself; it’s a very intimidating thought, to put a candid or confessional post into this engine that has something like a billion photos uploaded daily. Just that act alone of getting consumed by this machine… it wouldn’t be my forum of choice. But it’s obviously someone’s.

I think it’s like auto-generative too though, in that way. The more you do it and the more people see it and the more people mimic it —it becomes just a norm; as it becomes a normal quality in this media the easier it gets. The less thought goes into it as it happens.

Is there anything that can compete with 10,000 likes as meaningful human interaction, or have the likes just replaced something meaningful in favour of nothing —in favour of the bed island?

KS: That came up when I was talking about the paintings. Each of them are loosely based on images that shitkicker posted; she posts innumerable butt pics from the bathroom mirror. Over-the-shoulder butt pics. So one of them is a play on one of those, and another was based on a meme that she posted.

Thinking about that in the context of these paintings, the only real questions that came up for me were thinking about value and time economy; taking this thing that’s very fleeting —a drop in the ocean of available imagery —and then turning it into an oil painting. These really charged art-historical references. And wondering if it gave value to the meme, the image —or if it took value away from the painting.**