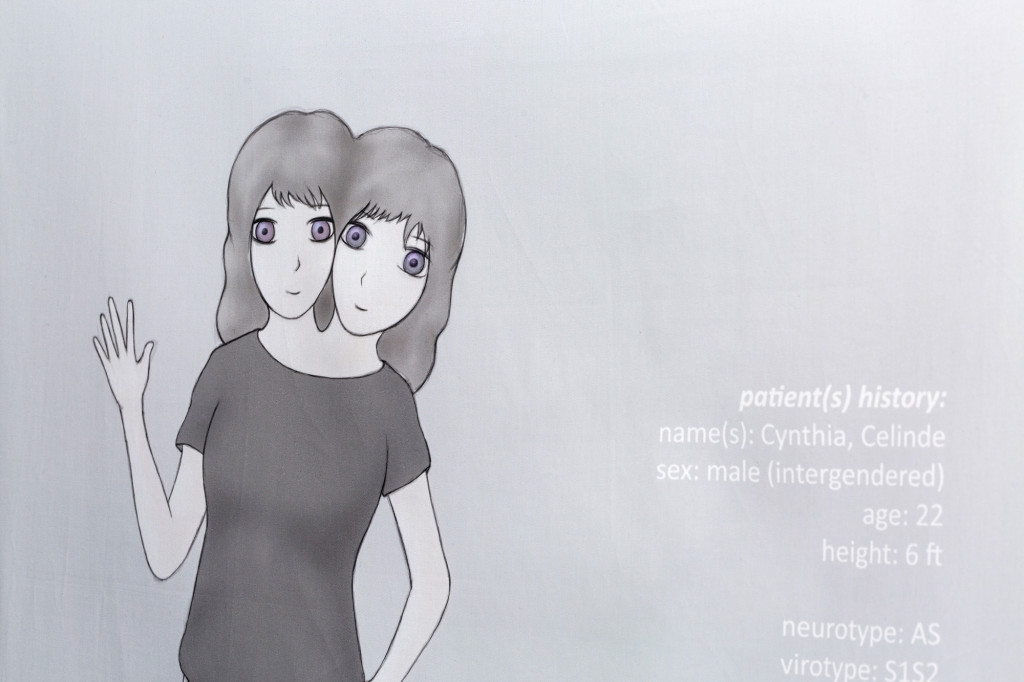

Andrea Crespo’s virocrypsis at New York’s Swiss Institute consists of a threshold. It appears as part of an installation at the Hans Schärer: Madonnas and Erotic Watercolors / Andrea Crespo exhibition, running November 17 to December 20 (Schärer’s exhibition runs until February), and later emerges in conversation with Hannah Black on November 18. Crespo’s works introduce what the event description calls “conjoined characters named Cynthia and Celinde”, guiding the viewer to a dark room, in which a short film loops. Clinicality, and how the sociality of neurodivergence is shaped by it, permeates the work: one portrait of Cynthia/Celinde, on display before one enters the film, lists their “patient(s) history”. The film itself employs imagery that is functional and mechanical, featuring a recurrent “clinical white line” that was also part of ‘Polymorphoses (epilogue)‘ (2015). The inclusion of computer fans and drops of water, loading screens and clips of cellular division, conflates the physical and the digital, the visceral with the technological, in a manner which both references post-technical identity politics and speaks to the medicalization of the body.

Etymologically, ‘viro’ derives from ‘viral’, and crypsis, in ecology, refers to the “ability of organism to avoid observation or detection by other organisms”. The ‘avoidance’ of crypsis can be used to frame the epistemological aspect of the work, primarily through its rejection of pathology as identity, and conflation of the infrastructural with the personal. Cynthia/Celinde’s assertion of their self -to quote the dialogue of the film, “It’s just us”, “Our perseverating embrace” -is at once singular and infectious, infinite.

The ‘perseverating’ of Cynthia/Celinde connotes multiplicity, within the self and within the user-generated, subcultural databases (e.g. DeviantArt) from which Crespo derives content. In conversation with Black, she speaks of avatars in these communities as “figurations they find for themselves” for lack of representation. These “subdivisions of the self” accordingly function to reimagine marginalized bodies as tenable in ways they are institutionally deemed untenable, as in sexuality. Eroticism in virocrypsis reappropriates clinical language (e.g. “ceaselessly stimulating”) to demonstrate how bodies alienated by or excluded from what is normalized as sex seek out other forms of tactility. It echoes the artists Camille Holvoet and Thanh My Diep, both of whom, as Jayinee Basu writes for Broadly, “challenge the longstanding public perception [that] people with disabilities are… asexual.” Diep’s work, specifically, is reminiscent of Crespo’s; the video ‘Nature of Pleasure’ (2013) shows two silhouettes merging to kiss, then overlapping, suggesting a desire for wholeness, communion, and (re)union.

Communion carries a theological connotation, which virocrypsis realizes as the embodied and the disembodied. One of the last scenes of the film discusses the ‘penance’ of Cynthia/Celinde in compelling people to emulate their communion with one another. I interpret the line “we’ve always been around” to allude to the Platonic Androgyne, written of in Plato’s Symposium as follows: “the two parts of man… each desiring his other half, came together and throwing their arms around one another, entwined in mutual embraces, longing to grow into one”. The incorporation of archetypal references suggests that Cynthia/Celinde’s ‘reprogramming’, estranged as it may seem, taps into something timeless. I see this as the principal connection between Crespo and Schärer’s work, namely his Madonnas: the infinite ideations of the figure, depicted as formless or ambiguous -even androgynous -in a way that emulates classical iconography yet abstracts from it, focused to the point of obsession, devotion.

And yet the overarching, private ‘avoidance’ of which this is part cannot -and, perhaps, should not -succeed. Black begins her discussion with the etymology of ‘sister’ as “one’s own woman”, reinterpreted for virocrypsis as “the shared impossibility of never being given a body in the first place”. Crespo’s film observes that we are “automatically mirror[ing] certain forms”, in ways that both oppress us and compel us to oppress. This problematizes the posturing of digital avatars as infinite or futuristic, as they often derive from unspoken historical and political contexts: Crespo and Black discussed the “teratological imaginary”, or the aestheticization of deformity, as a post-war, post-nuclear phenomenon, deriving from East Asian collective trauma. The ‘zombie’ as a symbol in US popular culture, was/is similarly decontextualized and removed from its origin in Haitian slavery. Crespo’s assessment of humanity seeking “conjoinment with machines”, in terms of transhumanist hybridity and sexuality, reminds me of sex robots -controversial bodies for how they can receive misogynistic violence, are “forms [men] want to fuck”. Black summarizes this in acknowledging that the posthumanist discourse often makes ideological proxies of technology for its perceived novelty, shifting the focus away from the persistent reality of racialized and/or gendered violence.

Similarly, the perceived novelty of marginalized artists is proxied by artworld discourse, centering the ‘newness’ over the reality of marginalization, over the artists themselves. Crespo begins the conversation acknowledging the fact that, at the reception for her opening, the director of the Swiss Institute, Simon Castets, misgendered her. Black related her experience to Crespo’s in saying, “our presences here are [both] some kind of achievement and some kind of lie”. Her statement speaks to the fact that the art institution does not know -nor fully understand -what it is curating. Hans Schärer, the influential Swiss artist and dead white man with whom Crespo is exhibiting, likely never faced such a fundamental affront to his work and identity as an artist. We must therefore always be critical of the motives of institutional inclusion, distinguishing attempts at reparatory understanding from, to quote Crespo, the “extract[ion] of cultural capital from vulnerable bodies”.**