Bunny Rogers‘ voice is unmistakable. Often described as flat or monotone, it is also sublimely expressive. At the opening of her solo exhibition, Columbine Library, at Société in July, Bunny launched Cunny Vol 1, an archive of the poetry she published on her Tumblr, Cunny Poem from 2012-2014. Downstairs from the exhibition space, in a grimy, empty flat, Bunny read from Cunny as if her words bore an unbearable weight. They visibly dragged her down so that by the end of each poem she seems to have to scoop herself back up before beginning the next. She reminds me of a character from a Dame Darcy comic book. Following the reading Joseph Beers performed Bunny’s favourite Elliott Smith song. The atmosphere was drenched in ennui; the acoustic strumming, the sticky floor, the black and purple stripes. It was like being in 1999 without nostalgia, as if for the first time.

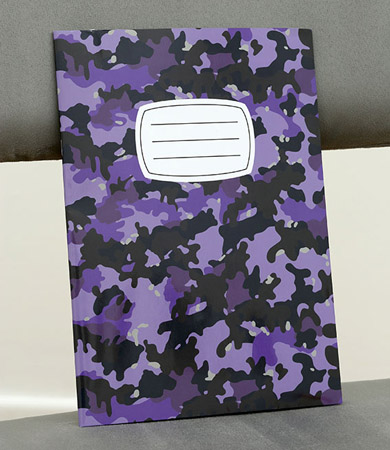

Almost two months later, the show is still open, Bunny has returned from New York with a series of multiples (her “merchandise”) and she is launching the Columbine Library artist’s book. A collaboration between herself, artist-writer Hannah Black, animator Elliot Spence, designer Guillaume Mojon and editor John Beeson, it is a picture book cloaked in purple camouflage posing as a school exercise book. Inside it is poetry, sad, intelligent and brutal.

Illustrated with a computer generated ‘photo’ series by Spence documenting the aftermath of the Columbine High School massacre, which Bunny’s show borrows as its ‘backdrop’, the images are slick and clean. Liquid pooling on cafeteria tiles is purple and grey, not red, it could be spilled fruit juice. The omission of gore, damaged humans, has the effect of off-screen violence. Rendered invisible it is felt rather than seen.

The subjects of Columbine Library and its opening ‘Unusuble Chair’ poem are inanimate. Utilitarian household objects, often chairs, often stood alone as disused usables, feature repeatedly in Bunny’s work. By turning them into art, by making them beautiful, Bunny renders these ordinarily expendable objects indispensable. She offers them value but not use. With her text, Hannah allows the Columbine chairs to speak, she gives them desires, she traces their convoluted agency. “They lie on their backs for the first time and hold their limbs to the ceiling … set free into uselessness, they will become…trash.” They’re offered meaning.

When I first saw Bunny Rogers’ ‘SELF PORTRAIT (MOURNING MOP)‘ (2013), I thought immediately of a scene from Disney’s Sleeping Beauty in which two of the fairy godmothers have a wand fight over the colour of Beauty’s debutante dress. An oblique, perhaps unintentional, but important reference, Hannah writes, “The old world is blue and real and imaginary, and the new world is pink and real and imaginary. At the corners they melt into each other, but the word love is fatally contaminated by violence.” At the climax of the magical, fairy godmother tussle, the dress is left ruined, stained pink and blue.

To quote Wangechi Mutu, “Females carry the marks, language and nuances of their culture more than the male”. This statement resonates throughout Bunny’s body of work, and significantly in this exhibition of which she has described her choice of subject matter to Harry Burke as “research into social absorption of the Columbine Massacre registered as a complex puzzle necessitating subjective assembly”. Hannah reiterates this sentiment as devastating poetry, “They all look basically the same – only the marks of use differentiate them… The marks of use and boredom.” In the story of White America, is the Columbine Massacre a fairytale, yet?

At the book launch, Hannah Black is reading. We return to the same abandoned flat underneath Société, but this time we file into a front room. Here the walls are bright, the floorboards look fresh, it is Sunday afternoon and the sun is out. Hannah’s words spin you off to other places, but you are in no doubt that you are with her in the room, hearing her words. She reads with a rare ease of presence, engaged in the present. This afternoon it is unmistakably 2014.

Writing this review, I am keenly aware of my desire to reference Hannah and Bunny not only as artists, but also as bodies. I recall a point that Elvia Wilk made at a recent Goldrausch Talk Series, ‘The Thing with Images’, that, at least anecdotally, when one searches for a woman artist online the query will almost always return pages of links to images of the artist herself, whereas an image search of a male artist’s name will show up pictures of his work. One only needs a basic feminist analysis to understand how being seen primarily as an image/body is one site at which women (not exclusively) are vulnerable to oppression and exploitation. That being consumed as a representation of physicality is a process of the body being denied its viscera.

The smooth, blemish-free underside of a round table with lanky metal limbs, spreads across centrefold, captured in image as if it were being watched from lying position on the cafeteria floor. On the following page, Hannah’s text, “now in the pause between worlds … this frozen time / living in an aftermath”, feels like the eye of a storm; a long waiting that stretches across the limbo time-space of the rest of Columbine Library. In the aftermath of what has been, there grows speculation of what is yet to come. Is there something eschatological about this current moment of feminism?

There are countless contemporary and historical examples of women artists whose works succeed in connecting representations of the body to the lived experience of its fleshliness, and by flesh I mean everything from the pink and green coil of an intestine to the electrical collectivity of intellect. Hannah and Bunny are two good examples of the diverse engagement of artists, ubiquitous in this regard. Their collaboration is brilliant and fleshy. There is something transcendental about it – almost divine – it embodies “the ecstasy of becoming trash.” **