I am still haunted by one of the worst nights of my life. I was a teenager, very active in my city’s art scene. I worked for a venue and, that night, supervised an event featuring mostly older male poets and performance artists. One of them started his set by singling me out. He claimed he knew me and had written a poem for me. He described it as “a poem for a girl you want to have sex with, who doesn’t know you want to have sex with her.” It was an ode to how he imagined my vagina, overwrought with symbolism of oysters, flowers, berries. I tried to leave the venue but was prevented by my employer. I stayed until the end of the event, escaped through the back door, ran as far away as I could. I wanted to hide. I found the stairwell to an apartment complex, enclosed by an awning. Humiliated and violated, I sat down and I wept.

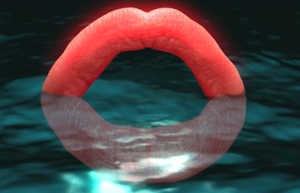

The Marxist philosophical concept of cultural hegemony refers to the domination of society by a ruling class, and the repositioning of that class’s worldview as the cultural norm, a universalized dominant ideology. In the patriarchal context, it naturalizes the subordination of women to men. And as an institution within cultural hegemony, art inevitably acts as a site of reification for this ideological relationship. This is true not only in terms of access to power — countless studies exist exposing sexism in the art world — but also of men’s and women’s comparative approaches to art, and to each other and themselves as artists. As such, a male-dominated art institution parses female artists misogynistically. Men and women are, additionally, encouraged to create as artists per how they are socialized. The above episode, for instance, evidences the practice of that male artist: to comfortably and acceptably project his subjectivity onto an object. It also signifies my status as an object within the institution. Moreover, my immanence implies a practice of its own, which is to allow the objectification, typification, and exploitation to occur, arguably to the extent that I participate in it myself. I find this profoundly reflected in my personal history. I was a female visual and performance artist who exclusively self-objectified in my work. I therefore only engaged with the institution of art through the pretense that I was an object, and my work served to reify that objecthood.

I attribute this to the combined forces of socialization and social coercion. The first is outlined by Simone de Beauvoir in The Second Sex, in her chapter on female narcissism. It works in tandem with ‘bad faith’ phenomenology, or, women accepting their subordination to men as natural and inevitable. She describes the phenomenon as a “well-defined process of alienation: the self is posited as an absolute end, and the subject escapes itself in it.” To me, my body was not my own, but an object in which I was situated, from which I was alienated. I could not conceive of myself as otherwise existing. As a woman, I had been socialized to understand objecthood as a fixed, stable social position. Because I am sexually androgynous, I have, since childhood, been subject to a heightened form of scrutiny vis-à-vis womanhood. Compulsory femininity manifested in the continual degradation of my behavior, affectations, and appearance as ‘masculine’ and/or ‘unfeminine.’ I internalized my anomalousness, becoming further alienated from/obsessed with my body and image through the constant reevaluation of my sex characteristics. Still I lived to appease men through self-sacrifice, which is to say, self-destruction (de Beauvoir continues, “the narcissist, alienating herself in her imaginary double, destroys herself”). My artistic work involved mirrors, disparate or multiple selves, and brutal self-documentation, which stemmed from dissociation, sexual dysphoria, and self-harming behaviors. I saw myself as incapable of merit, and unauthoritative in terms of the conceptual framing of my own art. I was, in every sense, a fetish object to myself, simultaneously glorified and hated.

This self-concept effectively facilitated coercion. My initial entrance into the public sphere, at age 15, was engineered by two men who controlled my life via physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. As my career progressed, I became the charge of various others, mostly men, for whom I was like a puppet or a plaything. They told me what to publish and produce, how to express and position myself, effectively shaping my private self through their construction of my public persona. One prostituted me; one attempted to steal my identity; through it all they referred to us as ‘collaborators,’ partners. Ultimately, these men were social agents, working to foster an acceptable womanhood in me by way of misogynistic oppression. My sexual exploitation in these relationships directly led to my becoming a sex worker. I maintained the roles concurrently, and I often thought of my exchanges with clients as reenactments of such victimizations. There is no difference, in my view, between an art world figurehead coercing teenage me to send him nudes, and a male fan of my former persona requesting that I flog him, or, for that matter, a client paying me to engage with his fetish. Exploitation is exploitation. In these examples, I am not an individual with subjectivity, but an abstraction, representative of sexual gratification and obligated to gratify. This is corroborated by how my work — which, despite a lack of self-awareness, necessarily expressed the emotional torment and trauma of my social condition — was often misogynistically misread, fetishized as masochistic. Accordingly, my most popular and best-received projects were those that exposed my face and body, and/or featured eroticizable (i.e. less disturbing) acts of self-harm. Much of the artwork sought resembled or derived from sex work and/or sexual trauma specifically — reenactments of reenactments. In rewarding exhibitionism as ‘aesthetic’, the art world effectively obfuscated my socialized self-exploitation from me, ensuring the extraction of labor would continue in perpetuity. By my 20th birthday, the sex worker and artist personae, far-removed from my actual self, merged into one dysfunctional public image: the ‘sadomasochist,’ externalizing and re-internalizing violence.

The combined influences of the sex industry and my religious practice of Catholicism were, paradoxically, what liberated me from this cycle, precipitating the resurgence of myself as a subjective being, rather than a traumatic abstraction. Both of these, as institutions, are, of course, fraught; in contrast to the art world, however, they brought me into stark, painful awareness of my own exploitation. The former was ideologically formative. It disproved the artistic notions of ‘performance’ and ‘authenticity’ with which I had aligned — the idea that a ‘performer,’ by virtue of his or her own self-awareness in ‘performing,’ has implicit control over his or her audience. My approach to sex work subsumed this fallacy, in that I thought my androgyny precluded me from ‘real’ womanhood, ergo from heterosexual recognition as a woman and the commandeering of my sexual labor by capital. But my androgyny is as irrelevant as my lack of authentic sexual interest in such labor exchanges — I still performed, embodied, and, therefore, momentarily became the object I was paid to be.

The combined influences of the sex industry and my religious practice of Catholicism were, paradoxically, what liberated me from this cycle, precipitating the resurgence of myself as a subjective being, rather than a traumatic abstraction. Both of these, as institutions, are, of course, fraught; in contrast to the art world, however, they brought me into stark, painful awareness of my own exploitation. The former was ideologically formative. It disproved the artistic notions of ‘performance’ and ‘authenticity’ with which I had aligned — the idea that a ‘performer,’ by virtue of his or her own self-awareness in ‘performing,’ has implicit control over his or her audience. My approach to sex work subsumed this fallacy, in that I thought my androgyny precluded me from ‘real’ womanhood, ergo from heterosexual recognition as a woman and the commandeering of my sexual labor by capital. But my androgyny is as irrelevant as my lack of authentic sexual interest in such labor exchanges — I still performed, embodied, and, therefore, momentarily became the object I was paid to be.

I found resistance in religious practice. I had always been a Catholic, but ‘bad faith’ obstructed and complicated my faith in God. My social condition prescribed immanence: my body was central to my worth, and I could not transcend it. Yet my subjective experience contradicted that. Even prior to becoming devout, I engaged, unawares, with mysticism. For years I had visions of angels and saints, and wept whenever I was in church, particularly at the sight of the Eucharist. I pathologized these occurrences but could not subdue them. My former self-concept faltered within this existential tension; my faith was irreconcilable with de Beauvoirian narcissism. I effectively and compulsively worshipped my own image, conflating self-hatred with the mortification of the flesh. This is religious, in the sense of Marx’s definition of fetish: an object, such as a cult icon, onto which the power of the abstract is displaced. Hence, I could accept, on some level, how my Catholicism, like any other aspect of my person, was fetishized; to fetishize me was to partake in the ritual. Now, I ‘authentically’ love God, and so I struggle very much with the idea that I, necessarily, also exist as a ‘Catholicized’ sexual commodity. This ‘good faith’ provides self-worth, a context in which to self-transcend, but it cannot change how I am mediated by society.

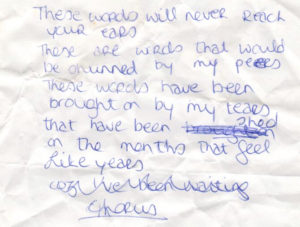

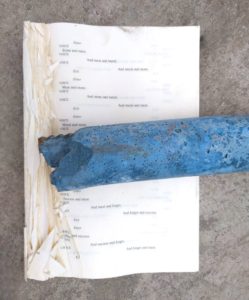

I often find myself questioning the utility of what could be considered, contemporarily or historically, ‘feminist’ art. Much of it attempts to elucidate oppression through, more or less, the replication and/or invitation of oppressive action. Can self-objectification truly be ‘performed’ without self-objectifying? Is the ‘performance’ of self-harm, a la socialized masochism, differentiable from self-harming? Given my experiences, I think not. I find kinship in artists who, rather than replicate the action, replicate themselves in a way that achieves distance. Bunny Rogers is exemplary. She produces her own fetish objects, such as the Mourning Mops (2013-). These are deck mops that Rogers dyes, soaks in water, and ties with ribbon. The mops are exhibited in corners, casually leaning against walls. They derive, but are abstracted, from her life and self, emotive but alienating to both artist and viewer. It is a self-annihilating practice, a conscious decision to remove, or estrange, oneself from one’s work, to negotiate the inevitability of one’s fetishization by society. Aligning myself thus, I changed my name, reinvented my public persona, and no longer feature my own image in my work. I, additionally, cannot relate to any old artwork of mine, which invites fetishism by its design. Even then, as I made it, I was alienated from it, compelled to act out a different sort of self-annihilation, in which I had no choice.**