On the same day that I send Melbourne-based writer Anna Crews a copy of the transcript from our second interview, she posts “‘Sent from my iPhone’ as a secret handshake for rich people” on her blog. I assume that she’s referring to me; to the signature generated by my electronic device, and relish the thought of being absorbed into Crews’s infinite tumblr scroll. Like most good writing, her work takes ideas you didn’t know you had and, in a series of casual insights, gives them the weight of common sense. Her book Magnum Ego was published earlier this year as part of the 89plus 1000 Books by 1000 Poets project, which features writing produced solely by people born in or after 1989, and as a result of this association Crews’s work is difficult to read without a reverent awareness of her birthdate. “As a 19-year-old girl, I’ll probably be infantilized anyway,” she says when I ask about the impact of this positive bias, “so my age isn’t something I want to feel shy about.”

Initially Crews was reluctant to speak to me in person, and when we did meet I was still so excited after an hour of talking that I accidentally deleted the entire recorded interview just after it had taken place, necessitating a second one. She’s tall, not great at maintaining eye contact, and was captain of the debating team in high school. Her smile is familiar to me from the photos she and boyfriend/artist Aiden Morse self-consciously post online, a performative response to their emerging status as a creative ‘power couple’ within the Melbourne interdisciplinary art and literary scenes. The affirmation Crews receives for her age, intelligence and heterosexuality (both in- and outside the context of her artistic practice) is something she embraces in her writing, self-identifying with outside assertions in order to work against them.

Crews writes about the subjective experience of sexuality, anxiety, vulnerability, choosing to opt out of academic overachievement, and operating as “girlfriend in an art context’’ next to Morse. She is interested in the potential marginalisation experienced as woman and poet to Morse’s position as man and artist, as well as the disparate values given to writing and art generally. If the job of the writer is to give art a language that translates into value – art costs money and writing is expected to be free – Crews’s most recent text ‘Praise for Aiden Morse’ demonstrates this valorisation literally. Written to accompany Morse’s solo show Soft Opening, she describes laying in bed sick and alone, listlessly masturbating over paparazzi pictures of Lara Bingle while looking at a test image for the exhibition where ‘’Aiden’s head had been photoshopped onto the body of some popstar and I’d also been photoshopped onto some popstar. It’s sort of a picture of us…But that’s like four people looking down at me wanking over Lara Bingle.’’ Crews manages to distance herself from the very images in which she is arguably the focus, from the safe space she inhabits as expert on, and subject of, these photographs. Her compliance in both this text and Morse’s images fulfils her role as ‘’trophy girlfriend’’ and a ‘’very good girl’’, but not without a characteristic self-awareness that challenges as it conforms.

You write with an honest perspective about your sexuality, using humour as well. Would you say you exploit the idea of femininity in your work?

Anna Crews: Yes. I’m interested in the idea of being protected. I realise that men like to think they’re keeping safe something pretty and young. I’ve written recently that I told a psychologist I didn’t like being introduced by Aiden’s friends to other men as “Aiden’s Girlfriend Anna.” The psychologist told me that this was a ‘secret man thing’, like they were sending a message to the other men that I was off-limits and that these guys were just trying to protect me. So, I suppose this writing comes from the safest possible position.

You’re intentionally provocative sometimes. How do you think this compares to existing self-representation of girls online?

AC: Hmmm… I feel like a girl being online in any way is always going to be provocative. You can either be ‘showing too much’ or not enough…

With self-awareness comes the ability to critique. I think there’s something appealing to people about the honest way you represent your sexuality, and similarly your awareness of the value that other people associate with your age. Being young gives you a certain kind of prodigal potential – or that’s projected on to you – and there’s a certain power in that.

AC: People do place a lot of emphasis on my age. Sometimes I wonder if they don’t like the actual work I’m producing, they just think that this work is good because maybe it will be better in 20 years.

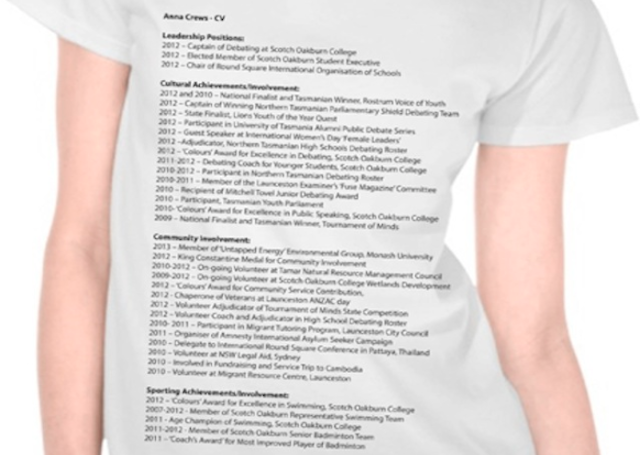

You kind of address that in the Gauss PDF project, where your CV has been photoshopped onto a t-shirt.

AC: I like to think of that shirt as self-promotion for the socially anxious, you could wear it if you can’t speak at parties but still want people to know you’re worthy of being there. CV building was something I’ve done a lot of at high school and university to show that I was using my time productively and was accomplished despite my age. A few years ago I was very proud of that CV. I still am conscious of whether I’m doing enough with my years.

So you do feel that pressure?

AC: I think it’s impossible not to. 89plus in particular has created a real emphasis on age. Everyone has a CV online with their date of birth so it’s easy to gauge where you stand in comparison to them. I often find myself looking at an artist’s website and thinking ‘if this artist is 30, I have eleven more years before I need to have accomplished or bettered what they’ve done.’

You discuss ideas around monogamy in your work, and particularly in your collaboration with Aiden. What appeals to you about this?

AC: Being in a monogamous relationship and being online means people get very invested in it. Your relationship broadens beyond just the two of you. People send us questions asking about our sex life. If we’re having a fight and I document it on my blog, people take sides and send me ‘messages of support’. People direct questions about me to Aiden and questions about Aiden to me. It’s like we’re authorities on each other. The health of our relationship has become something many people are concerned with.

Why do you think people are so into it?

AC: It feels like putting on a spectacle. Doing something hetero, like posting a sweet picture of us going to dinner gets us more attention online than any of the other work we do.

Regardless of people’s political opinion of heterosexual relationships, I think it’s still something that everybody feels obliged to support. The most consistently popular posts I’ve seen on Facebook are marriage-related. If we got engaged I’m sure that would be cause for a lot of positive attention.

I like the transparency you present, for example posting a picture of yourself on the way to Aiden’s exhibition and forecasting the way you might feel there.

AC: When I made posts about Aiden’s exhibition I was thinking about how I am a trophy girlfriend or a greeter at the gallery. It’s a supporting role – you’re there to make it pleasant. It’s something I often see in an art world disproportionately dominated by men. The girlfriend in an art context is someone who stands next to the artist, is nice to the collectors and makes conversation. No one asks about her practice in the gallery or when you go out for beers afterward. The female artist can easily be reduced to someone’s girlfriend.

How do you feel about the literary scene at the moment, in terms of long form pieces published in journals?

AC: I think literary journals are declining in relevance. Their approach to writing seems a bit old hat. No journal will publish a previously-published piece and it takes a lot of effort to create many different pieces in the hope that one will get published. And even if a piece does get published, it won’t generate as much attention or feedback as it would if I posted on my blog. From publishing something in a ‘mid-range’ journal, you might get 5-10 click-throughs to your site, if you’re lucky. And that’s a piece you can never show again because it’s bound to being published only in that one place.

When I think about how people treat art – how the same painting can be shown in multiple group shows all over the world or an edition of prints can be sold without anyone caring – I realise that literary journals aren’t giving writing the value I think it deserves. An alternative to this seems to be presenting your writing in an art context.

How would you describe writing in an art context?

AC: I don’t quite know yet. I guess you’ve got Jenny Holzer-type texts that assert themselves as physical art objects, but mostly every time I see something done like that or try to do it myself it ends up looking like what’s already been done. But then there’s also people like Rosemary Kirton and the Paradise Structures twitter, whose writing is very aware of what’s going on in art and doesn’t seem traditionally ‘literary’. Their work is new, interesting and exciting to me.

Would you ever present your work in a different format to what you’re currently working in?

AC: I’d like to. I do feel comfortable working on a blog with infinite scroll, though. It would be hard to find something I liked as much.

Do you have anything coming up ?

AC: Mostly I’m working on stuff for next year, brainstorming things. I don’t know where I fit, I don’t want a book, I don’t want a solo show, maybe I’m too picky.

Anne Crews is a Melbourne-based writer and artist, author of Magnum Ego, published by 1000 Books by 1000 Poets, and contributing text to Aiden Morse’s Soft Opening at Fort Delta, running September 18 to October 4, 2014.

Header image: Anna Crews and Aiden Morse self-portrait, image courtesy artist.