A cursory examination of Emily Jones’ practice suggests an engagement with current accelerationist rhetoric: that aestheticised taxonomy of collapse where nature systems fall and decline, technology mutates organically, dolphins swim kawaai through toxic sludge and tribal peoples wander around wearing Nike in the endless flattened desert of the real. But Jones is a different kind of taxonomist. The point seems not to illustrate the sameness or equivalence of things, but to invent systems – algorithms, even, though the terms of the equation are obscured – by which she (and we) might understand the world.

The Hudson River, Jones’ recent solo show at Lima Zulu project space, is an installation composed of organic matter, paper, fabric, tape and text. The latter appears in object form – individual words printed large on white A4s laid out in several symmetrical lines on the floor in parallel to the wall – but also as a kind of ghost data that remains in the air. This ghost data comprises traces of a reading given by Jones at the opening (John Locke’s 1689 text ‘An Essay Concerning Human Understanding’) and an exhibition text distributed on paper and on the facebook event page:

“A database of medicinal plants of Bangladesh – A history of prophecy in Israel – The foraging success of the Scarlet Ibis – Treatise on the propagation of orchid seeds in vitro – Pigeon Homing as a Paradigm – The Lake as a Microcosm.

I instinctively put the rose quartz in my mouth and she tells me I shouldn’t do that.

(It still stands)

#chthonic #oneiric #apotheosis.”

Here, the vernacular and the experiential collide with the global and colossal, as with Jones’ earlier digital collages ‘Is that a castle over there? No, it’s a nuclear power station’ (2010) and ‘The Endolithic Biome’ (2010). There’s nothing in the space but a big yellow melon and a folded fabric printed with a blue earth swimming in space, while the words around the walls are like some kind of early computing system, machinic in form and alchemical in affect. These are dictats, incantations, commands in a command-line: exchange cultivate expand multiply magnify. They’re grouped according to their phonetics, arranged for pleasure of the tongue: invoke evoke. I don’t see it at first, but there’s a row of white soap cakes lined up by the door as though packed for sale fresh from the factory. There’s something about their ‘silence’ – and I’m talking about a silence particular to things as they might exist unanimated by the ostentatious theatrics of art or commerce, a thing-being untroubled by irony – that seems to communicate something of their journey, their production before being soaps on a shelf or on the floor in a gallery. This too is offered quietly, without judgment.

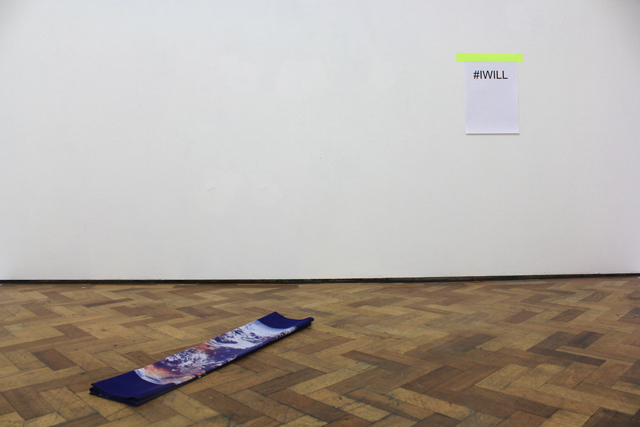

The sole wall-based element is a sheet of paper that reads #IWILL. It’s held in place by a single strip of neon tape and it holds the whole thing together, both formally and metaphorically. The lightness or slightness of the work might be, on some level, part of the message: that the system of things by which we live is delicate, intricate, organic and precarious. The Hudson River (in addition to living one of its lives as a waterway in greater New York) exists simultaneously as a temporary art installation in North London and as a space online that is part archive and part narrative: a girl and a glacier sit in among the documentation on Jones’ website, along with text not present in the space. to imagine a language means to imagine a form of life, it reads. In the end, every algorithm is linguistic and no algorithm will save us; there can only ever be an intention – which is the function of language – and this alone makes magical sense of that which we can neither control nor fully understand. #IWILL is an expression of the will to live in among other living things. And the will to live – common to the human world, the animal kingdom and the accelerationist fantasy of technological singularity – is the most mysterious organic notion of all. **