Prolific German pop-artist Martin Kippenberger once said, “A good artist has less time than ideas,” and when it comes to Brian Eno, said truism couldn’t be truer. At 63-years-old the pioneer of ambient music is showing no signs of slowing down and recently he’s been splitting his time between his 41st album and scoring the never-repeating melody for the 10,000 Year Clock. He’s worked with the likes of Grace Jones, Laurie Anderson and Depeche Mode over an extremely productive lifetime and poet Rick Holland is pretty chuffed for being able to count himself among the ‘generative sound artist’s collaborative vanguard.

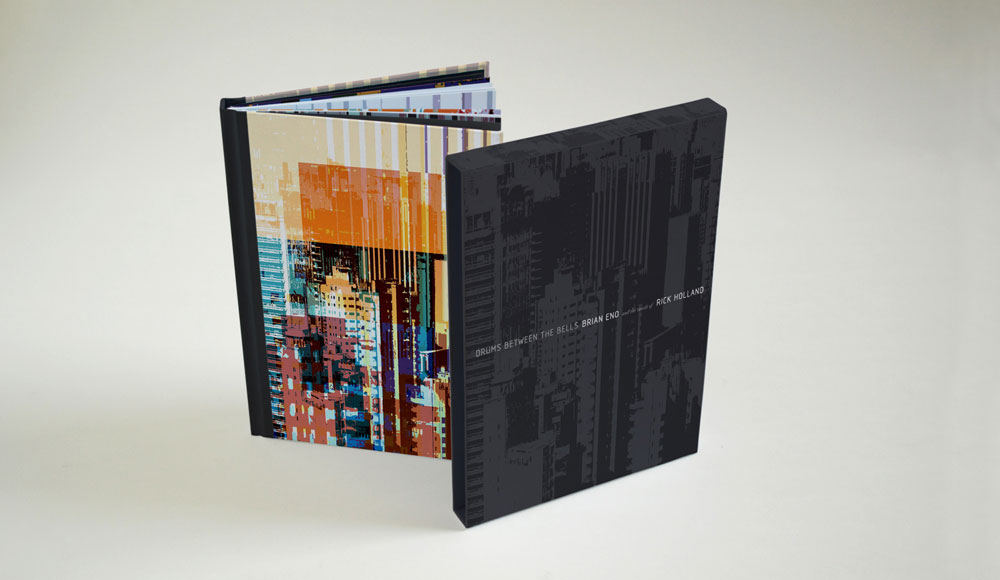

Eno approached Holland way back in the early millennium when the word-smith was just starting out in live performance and they’ve been working together ever since. Funnily enough, Drums Between The Bells, a collusion between musician and poet, is the first we’ve seen (and heard) of their produce and what a brilliant thing it is. Compounding words, images and sounds into a kaleidoscope of perspectives, the music is as busy as Eno and the Sao Paulo skyline featured in the album art. With Holland coming from a military background, with its nomadic lifestyle, and Eno being on a whole new plane of experimentation, Drums Between The Bells combines the universal outlook of a globe-trotting writer with the conceptual journeys of an artist that is out of this world.

aqnb: I can’t actually find much information about you online, can you tell me a little bit about yourself and what you’ve done?

RH: It’s really patchy to be honest, that might be why it’s not anywhere in one place. I lived in London from about 2002 until around 2009. I was there with writing in mind but I did a whole heap of different jobs while doing the writing on the side and trying to live around it. In that time I worked, and continue to work, with friends I met who were all music students. Through that I ended up doing some work with the Heritage Orchestra, as well as lots of experimental work with different musicians. It was during those years that I met Brian, basically.

aqnb: So you’re a bit younger then?

RH: I’m 32, so I was quite young when I first met him. I was 23, I had just started working with music and it was at my first show with the Guildhall School of Music and the Royal College of Art. The short of it is we did this improvised music and poetry section for it, Brian was there and I met him after. It was the first public performance of any scale that I’d done, so it was outrageous good luck on my part.

aqnb: Is that why it took so long for you both to release something?

I don’t think so. If I’d had more experience maybe I would have pushed harder to get something done in the early days but I don’t know if that would have made any difference. I think the reason it’s taken so long is that we just didn’t really know what we were doing to begin with. The first experiment we did was really exciting and I thought it was a great piece. It’s not on this album but I would say that some of the ones immediately after that weren’t as successful. Plus, him being him, Brian had so many different things going on and this one was just easiest to come back to as and when the moment took us.

It did have an influence on how I was writing my own poetry, though. I definitely then started writing more with music in mind. Not solely with it in mind but there were more times I sat down and actually thought how it would work in a musical setting.

aqnb: There’s something about music that I’ve always been quite envious of; the way that it can capture your imagination without having to think: it’s there, it fills a space, it’s unavoidable. Is that something that you pursued, collaborating with musicians?

RH: Absolutely, I’m a 100 per cent with you on that. I’ve always tried to get that same experience through using words, even though I know that I couldn’t ever quite get there; the effect of music is out of reach but it is this ideal end product. I’d love to achieve that primary connection, between the words and sensation, or the words and emotion, without needing so much digestion and rumination.

aqnb: With poetry, especially, that’s usually the aim. The sounds, the enunciation exists to generate a sensation that is more than literal and that’s what you’re playing with on the album, getting music out of those words.

RH: That’s true. When you get a melody that is repeated, it does different things to you each time you hear it. I’m really into the idea of floating images in a way where they’re not tied into a poetic whole. They don’t have to follow from point A to point B to point C; they can just be floated there. That’s the kind of stuff that really appeals to me; whether it’s hip hop lyrics or anything, something comes out of the ether and grabs me. That’s my ideal when I’m writing and when I’m listening.

aqnb: The ‘Silence’ track on the album; is that something taken from your background because silences and spaces and the way you set out a poem is very important?

RH: That’s a really interesting angle but the silence was purely because the final track, ‘Breath of Crows’, was too much of a removal from the tone of the album, no matter how many times we fiddled with running order. It was just too difficult to make that leap, so we thought the only way to set that up and get your brain ready to take on that track was by putting silence before it. That’s the honest answer to that. I’d like to say something cleverer but that’s what it was, really, and it works. It gives you a chance to let the silence wash over you and reset your default settings [laughs] to take on ‘Breath of Crows’.

aqnb: What was the process of writing? Would you come to Brian and work together, or would you take his music and write to that?

RH: I would have loved to do that. That was my instinct when I first started and that’s what I was doing with other people, using music to trigger words but that’s not really how it worked. I did take a few pieces away and write words to them but they tended to be things that didn’t end up getting used.

Really, the ones that worked, or the ones that really interested Brian, were the ones that weren’t so tied into that process of writing. I went into the studio and he said ‘right, I’m working on this. Do you have anything that fits the mood or, for whatever, reason would suit this?’ Then I would rifle through whatever I had brought with me. We tended to do it like that and make decisions relatively quickly. A lot of decisions were made after the voices were recorded and who spoke it; that would be a very good musical starting point. In a way I had to surrender the meaning, or surrender what I’d done or I’d been thinking, when I wrote those words down. I put the words down and then a new set of options was thrown up from that. It’s a different process from what I would have been used to.

aqnb: Assuming that music can express things that words can’t, if you take that more limited form of expression and then expand on that, it’s like you’re adding meaning that might not have been there in the first place.

RH: I think that’s exactly right. That’s why there are different levels to this record. For someone who is extremely word-centric and concentrates hard on them, I do think meanings come out in a similar way as you would if you set them out on a page but there’s also a whole new range of meanings that are nothing to do with me.

Whenever you write a poem and someone else reads it, the meaning, the source of the meaning, is taken away from the writer and it’s in a new arena. That arena is what the person brings to those signifiers, those words and their meanings.

I’ve always been aware of that but in this I was really conscious that, as well as handing over that meaning, I was also handing over the way it was delivered in such a way that there were all of these wonderful new accidents of expression and sounds. It’s quite hard to explain it in words but sometimes there are effects going on just in the way a few syllables are pronounced or the way that the voice warps what’s being said, that actually sets you up in a completely different direction.

Brian Eno – pour it out (taken from Drums Between The Bells) by Warp Records

That’s why, if you came to this album completely cold, some of it might seem a bit plodding and ponderous. It takes a bit of an investment, or a bit of time, to let those effects happen. I’ve listened to it so many times, over all these years, in its various forms, but I still come back to it. There are times when a track starts and I think, ‘oh no, I’m not going through this again’ but then, within ten seconds of putting myself in that zone, it starts having these wonderful effects on me again.

aqnb: There are so many facets to the album. Your words are changed based on the way Brian’s music accompanies it, the way it’s read and then the way the vocals are manipulated within that. Did you have much input into how the words were visually presented in the booklet?

RH: I did sit down with [designer, Nick Robertson] and set out the poems. Over the years these poems would have got to Brian and got to his studio in such different ways. A lot of them have never actually been written out before, in this way. Some of them were written at the time, some of them were emailed to him, some of them were scribbled on paper. The process of making the book with Nick was I’d sit down and write all the words. I literally transcribed them in the lines that they appear in the pieces themselves because the way they’ve been set out in the book has changed as a result of how the music’s ended up.

Brian Eno – bless this space (taken from Drums Between The Bells) by Warp Records

Brian Eno – glitch (taken from Drums Between The Bells) by Warp Records

aqnb: Do you think the accents of some of the speakers were important to the overall outcome?

RH: As a general rule Brian looked for voices that were non-native English speaking voices. He did that on purpose because of all those things you were talking about before, those accidents of enunciation and interesting melodic elements of the voices.

aqnb: Does that lend to a greater concept at all? The skyline of the cover art is Sao Paulo, as well. It’s quite a global idea.

RH: Without it necessarily being a conscious thing, I think it adds very much to that. The ideas of pattern formation and different the perspectives of the album, I do think it helps that there are so many different types of voices in there speaking.

aqnb: Perhaps it is the universality of cross platform art creation and communication?

RH: Yeah [laughs] nicely put, I like it.

aqnb: I think I’ve found the closing line.

RH: Yeah, you don’t need to write anything else, that’s the one.

‘Drums Between The Bells’ is out now