When thinking of the art of Dubai all sorts of images spring to mind. They’re mostly those proliferated by people who’ve never been there, a hypercapitalist utopia where money is free and the wifi is ubiquitous. It lends itself to the transmedia haven that Andy Battaglia characterised in reference to the work of James Ferraro and Ryan Trecartin in a 2011 article for The National, two prolific artists who work within a complex feedback loop of fascination and repulsion with the virtual dreamscapes that places like Dubai have come to represent. Neon colour schemes and CGI graphic spaces iterate the real though unsettling pseudo-realities of globalisation, while the consumer trip of fun and post-irony come in the form of “killer tanning” and “crazy nights” in performer Lauren Devine’s ‘This is How We Do Dubai’. But what of the city’s reality?

Between Business Bay and Internet City, lies the Noor Islamic bank stop of the Dubai Metro. There you’ll find, hidden in the barren industrial district of the Al Quoz, Al Serkal Avenue, a container compound housing over 20 art spaces within a single block radius. It’s very hard to find without a UAE Art Map, even more so on foot, in the heat and down the pathless roadways. But once you do, it serves as an interesting microcosm of globalisation and the fragmented way we perceive and contextualise a world experience, increasingly dictated by the web.

A mirage of the imagination that took me hours to find, a creative haven of galleries, peppered across a small map and separated by the real-life external hard drives of their metal containers, exist. Inside The Third Line gallery (not actually in Al Serkal but nearby) were the works of artist Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian of exquisite glass cut mosaics, three dimensional sculptures fastened to the walls and fashioned in the style of the Muqarna, a distinguishing element of Islamic architecture and ornamentation that can only be truly appreciated in a physical space. Further down, now in Al Serkal, there are works by Iranian-born Australian Hossein Valamanesh in Grey Noise, his selected works from 1992 to 2013 containing one of the few multimedia pieces ‘Passing Time’ (2011); a monitor featuring two disembodied hands fidgeting on loop and hidden in a bowl on the floor. Carbon 12 presented Olaf Breuning’s Camelops Femina series, featuring Occupy eccentrics posing as camels on all fours, while global Ayyam Gallery was closed for installation; an exhibition of pieces for auction, targeting young collectors who could pay between one to 10 thousand dollars.

The most moving work comes from Helsinki based, Iranian artist Abdel Abidin’s, Symphony, a suspended light sculpture in the form of huge bird dragging a white stone to the doomy drone of a pervasive soundtrack, a 3D rendering of a morgue is nearby, featuring a totem per teenager killed during the 2012 “emo” stonings of Baghdad.

It’s true that the art in, rather than about, Dubai still functions very much in the physical realm, a part of an economic reality where culture and art production has become more and more central in profit making and investment. It’s a frightening reality in the context of rapid expansion and development that is unsustainable in the face of imminent environmental collapse. That very query was most strikingly expressed in a photographic exhibition of Dubai-based artist Richard Allenby-Pratt’s Abandoned, featuring his impressions of a projected 2017 apocalypse, leaving the UAE city deserted, only to be reinhabited by the world’s most resilient desert animals, from emus and kangaroos to giraffes and meerkats. Perhaps, this is at the centre of all the works, between countries, cultures and subcultures, as an unsettling awareness of the corruption and decay beneath the pixels; an unregulated growth inevitably hurtling toward its own destruction. Because, to find the stark LED’s and exoticised fantasy of the Dubai of a Western imagination, you need not look any further than the hyperreal spaces and levitating seats of an Emirates Airline safety video. It’s an illusion of security and control in the face of impending doom. **

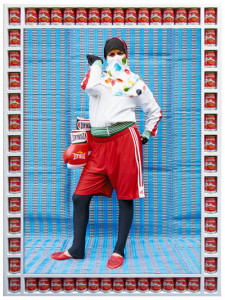

Header Image: Richard Allenby-Pratt, Giraffe (2012).