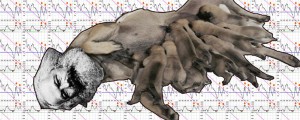

Geoffrey Lillemon‘s online campaign for Bernhard Willhelm’s Women SS 2013 brings to mind a picture of Stelarc‘s younger, crazier brother. Using Faceshift and 3D Studio Max, Lillemon creates a colourful, vivid bunch of virtual models with an elfin appearance; resembling 1980’s Troll toys as much as they do Future Sound Of London. Each project in the collection is represented by different custom-designed creatures, which, paired with intensely patterned, vertigo-inducing design and the shape-shifting cut of the clothes themselves, create an atmosphere of digital, GIF-based sensory overload. Back in the day, the psychedelic gurus of the 60s sought a new frontier for their mind-broadening pursuits in the digital world; works such as this seem to be their distant, less ideological echoes.

American multimedia artist Lillemon, made famous by his participation in the Champagne Valentine collective, is active both in high art and the commercial field. In 2009, he made an award-winning installation at Tate Modern (together with painter Miroslaw Balka), yet at the same time he succeeded in interactive advertising during its most successful period, working on campaigns for VH1, Versace and Diesel.

Lillemon claims that he “brings a classic romantic drawing and painting style to technology”, but what makes his work interesting is his approach to early 1990s computer graphics. When they were supposed to evoke an atmosphere of the future, their technical limitations couldn’t live up to the ambitious objective; the 3D future was disappointingly heavy-handed. Even artists once considered pioneering and ground-breaking, such as the aforementioned Stelarc, appeared stuck in an imaginary future, passing unnoticed while digital media began to develop in different directions.

Years later, freed from prophetic or visionary obligations, that flashing, angular, uneven early digital art can be revisited as an interesting medium. Geoffrey Lillemon plunders those 8-bit colour realms, expanding and twisting them in a mildly postmodern manner. The best example is Rainbow X Apocalypse, an animation which recalls the aesthetics of 90s racing games like Wipeout 2097 and at the same time manages to induce a hallucinatory feeling, similar to the visual effect caused by pressing one’s eyeball. Lost Planet could easily be taken for a vanished Psychic TV video. Regardless, their main aim remains to create a mood, which makes them a visual equivalent of ambient music at its most buzzing, blinking end.