The human mind is trained to see the absence of light as darkness. Darkness in and of itself does not exist. It is both a negation of presence and a totalizing void upon which light is cast. The origins of darkness exceed the movement of light, and yet to unknown ends. Tracing back to the source of light may proffer answers. As an extrospection of this incomprehensible dark, Seoul and Frankfurt-based artist Muyeong Kim, presented his first solo exhibition, House on Glabella, from December 10, 2021, to February 12, 2022.

The site of the show, Seoul’s Museumhead, acts as a camera obscura; a dark, enclosed room that is awash with a deep lightness penetrating through a fissure. Just outside the exhibition space, a single speaker dangles from a chain—incognito against the withered veins of vine that scrawl the wall of the adjacent building. The eerie noise of ‘Lesson’ (2021), a sound piece created collaboratively between musicians bela, Hanjoo Kim, and Kim himself, fills the crisp winter air, prefacing or extending the tonal atmosphere of the show to outside.

The following writing recounts encounters with three variations of a disorienting vision created by Kim that illuminates the concrete chamber.

I.

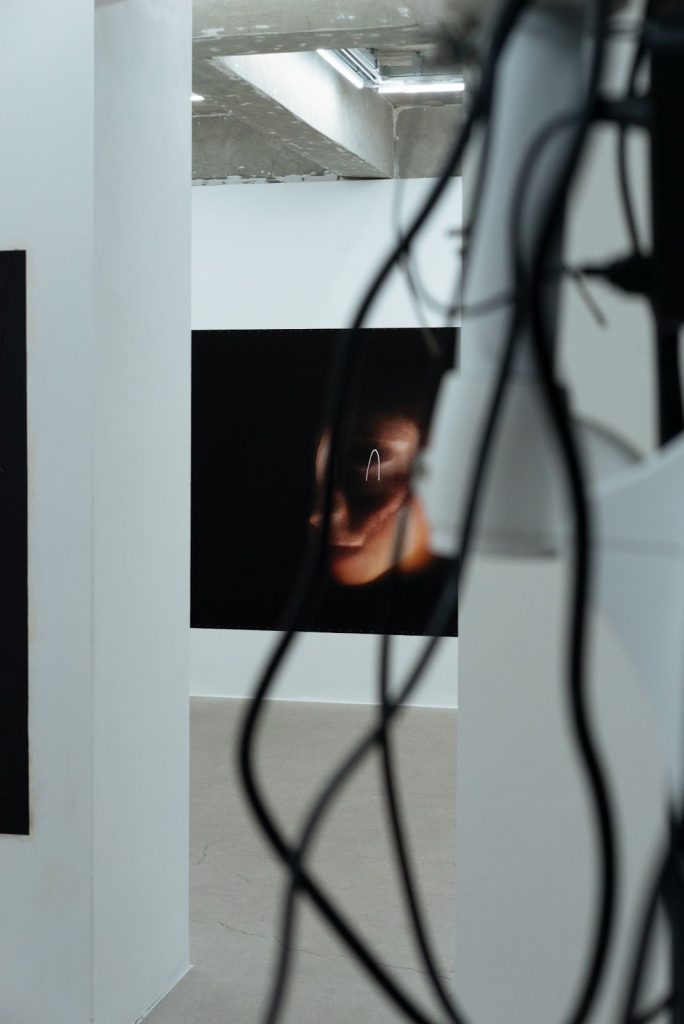

The Museumhead exhibition space is interspersed with recent photography, videos, and paintings by Kim and his frequent creative collaborators: the aforementioned bela, Hanjoo Kim, as well as Kitty, and Hyein Min, Jiyoung Wi, Yonsok Yi, to name a few. Within the brutalist-style interior, speakers are affixed mid-air with metal chains intertwined with the wires, TV monitors are mounted onto dense, white, metal armatures used in dentist offices, and some photographs are nailed directly to the wall. Let’s begin with the phantasmagoric photography prints, as they offer a direct insight into Kim’s unique way of manipulating digital devices to capture an image.

‘Why you two never look at me’ (2021) is a portrait series that uses the Stage Light mode of the iPhone camera. It detects the forward-facing person as the foreground and simplifies the rest as a darkly-tinted background. Kim uses the default shutter speed and the algorithm of the camera mode to detect a singular subject against itself. Vigorously shaking the device, as if holding a brush against a canvas, he actively paints a loop-hole in its mechanism. Contradicting its innate purpose to generate a sharp, clear image in a swift instant, the resulting photographs are a glitch, a glow—a chasm through which a blurry and distorted figure appears. The intense jerking motion fragments the dark, creating apertures for vivid colors of faces and body parts to be abstracted and emulsified as ghostly specters of the light.

The ‘Why you two never look at me [h 133/272]’ (2021) portrait series is pasted flat directly onto the wall with a glossy finish. Selected from 272 takes, the 133rd shot wrinkles against the cool, hard surface creating a wet tactility to the image. Like the wrinkling of human skin, or the crevices of tree bark, its texture underscores a sense of temporality. My gaze directly locks on to the blazing eye captured within a rhombus-shaped glint, glaring intently at the camera. It is the vast areas of darkness, however, negative spaces programmed to absorb all that surrounds the detected subject, that is brought to the foreground. This overpowering opaqueness becomes singularized units in Yi’s paintings, which, alongside ‘Fault (in three folds)’ (2019, 2021), address Kim’s sustained interest in the afterlife of performances. The two works can be considered part and whole of the artist’s 2019 performance ‘Nimbus’—proxies that raise the question of how a time-specific work is remembered and archived.

Situated in the temporal and physical landscape, where Kim’s past and new works co-exist, the four solemn wooden blocks by Yi expand from their original presence as references to ‘Nimbus’ to a newly attained sense of agency. Using tar and oil on each wood, Yi portrays a unique sense of the marred or the tainted. Some of the surface is treated with a matte finish and violent hatch marks. The fluidity of morose hues and simplicity of the calculated engravings appear as an abyss in the wall, a break in-between, a black mirror that encourages the viewer to turn unto themselves.

In ‘Nimbus,’ the videographer documenting the performance is directly incorporated into the scene but is given instructions that differ from the other performers. The guidelines, which had only been presented to the cameraperson at the time, are revealed to the public as three loose-leaf pages entitled ‘Fault (in three folds)’ (2019, 2021) in House on Glabella. It circumscribes the movement of the person recording to excerpts of Hollywood’s Motion Picture Production Code. Dictating the language and behavior on the morality and responsibility of art, these original rules forced many major US film studios in the mid-1900s to self-censor any form of profanity. Upon reading Kim’s documentation protocol, which is positioned at the center of the space, the areas of black, found in almost every photograph on display, then take on different implications. These territories can be re-contextualized as censors that omit information. It is a deliberate secrecy that redacts information about the image in its entirety.

II.

There is a paper program distributed to viewers ahead of the live ‘House on Glabella’ (2022) performance, including a short text by Kim. In one of the paragraphs, the artist details how a gun scene is produced in a low budget film set. A person aims the weapon toward its subject, and with calculated scene blocking and meticulous camera angles, the shooter and the victim signal the release of artificial blood and subsequent performance of death through eye contact. Focusing on the irrefutably tense, linear line of vision that is formed in this split second before the bullet leaves the gun, an invisible thread pierces through the perpetrator’s gaze, down the barrel, and nestles onto the precise spot between the eyes of the receiver of the anticipated bullet. All at once, the exchange of eye contact between the shooter and the target conjoins them in their opposing relationality.

This tense exchange of gaze can be found with hypnotic exaggeration in a particular act in ‘House on Glabella’ (2022). A performer (‘the pointer’) directs their index finger intensely to the start of the bridge, which separates the left from the right eye—the glabella of the opposing performer. Crosseyed, this performer (‘the gazer’) converges their trembling lines of vision upon the tip of the index finger. The starer is mounted on the back of another performer (‘the crawler’) who is on the ground on all fours. Feet to hand and hand to feet, the crawler moves forward while the gazer affixes their attention to the movement of the pointer. The three performers move in slow unison: the gazer’s line of vision is dictated by the pointer, while the pointer’s aim is determined by the crawler. Their orchestrated steps are held together by a singular ocular focus, tending toward a desire for the autonomy of sight.

Now, let’s replace the gun and the index finger with a camera. In ‘Bed Confession’ (2021), co-directed with multimedia artist Hyein Min, the shooter and the protagonists engage in a hallucinatory visual dialogue with the mediation of the camera. Punctuated sporadically with the wispy sounds of a flute, the video documents the movement of two figures in a hotel room. The orderly white bed and dull decor are swathed in tungsten light, while its temporary inhabitants shift restlessly under a stiff, cool-tone spotlight. The videographer and the subjects are in intimate proximity to one another; the confines of the space constricting any breath for secrecy. There is also a sheet of fresnel lens placed in various parts of the mise-en-scene. By incorporating the flattened convex lens within the scene, Kim alludes to a personification of the room, or a spatialization of the physical body through the exaggerated proportions and depths of field.

Appearing as another camera lens detached from its body, this glass sheet distorts viewers’ understanding of which direction the recording device is actually pointing; it is as if the camera is mirroring what is behind, rather than what is in front. The realms of foreground and background are rendered interchangeable. Between such dialectical play of vision, the detached lens peels back a layer of reality, acting as a portal to another dimension. The viewers witness a duplicitous telling of a story without a storyline. The sweet release of tension never arrives, and the shooter and their subjects remain locked to each other’s gaze.

III.

Kim’s visual language is cryptic, heavily layered with references from film, literature, and Greek mythology, to name a few. He works in an iterative manner, allowing the viewer to notice recurring technical choices and patterns that culminate into a kaleidoscopic narrative. In House on Glabella, the various methodological and conceptual frameworks are informed by the idea of doubleness, its imposal of the binary, and the ways to break free from its entrapment.

Take for example, ‘Socket: Lateral exits, Chiaroscuro as a Predicament, Dollhouse’ (2021), which was inspired by a documentary on the Siamese twins. Kim cast Min and her mother as the performers, exploring duality as a shared identity. Divided into three chapters, the video begins with the pair in a living room loosely imitating one another’s actions at alternating times. Then, the opacity level of the shots are lowered to overlap each other, becoming a rhythmic movement of a couple of individuals converging and diverging paths. In the following section, the faces of the mother and daughter are drawn from the dark with a harsh spotlight. Again, their isolated portrait shots are overlaid, emphasizing how the resemblance of their familial faces transmogrify into one another but never enmesh as an exact similitude—it is a oneness expressed in two. The video’s hallucinatory editing conveys a sense of lucid dreaming, which is a disorienting experience, where consciousness is split in two—one fast asleep, and another wide awake—wandering and entangling in irrational ways. In such a state of limbo, one experiences the contradiction of having a heightened awareness of ‘un-reality,’ while simultaneously feeling the images of the mind as tangibly vivid.

The last chapter of the video, entitled ‘Dollhouse’ is roughly a minute long and reveals an entirely different performer. Wearing an all white dress tied with a thick white rope in bondage style, Kitty, who has appeared in many other works by Kim, occupies the same place where a mirage of the mother and daughter seems to still glimmer. A striking luminance to the haunting scenes prior, the final frame serves as a prelude to the aforementioned live performance of ‘House on Glabella,’ where Kitty takes center stage.

For two nights, House on Glabella becomes the backdrop of the eponymously titled performance. Viewers first shuffle into the exhibition space in the dark, finding their way using their own phone flashlight. The shifty flickering eventually dwindles, and only a strange red glow from one phone torch shining inside of someone’s mouth and two white rays emitting unhindered from phones held in front of another person’s eyes can be seen. From the seemingly endless inertia of the visual and aural, sudden shrieks of industrial noise strikes, and a grayish dim enlivens four performers in repose to arise.

Within the boundaries naturally formed by the freely-moving viewers, the setting consists of an array of props for the performance: a grand piano, pieces of semi-transparent latex sheeting, a helium tank, and a rectangular sheet of glass. Kitty is distinguishable by her halterneck, backless dress while the other three don black, tattered clothes of denim and leather with loose strings and clunky shoes. What is most striking is the Ken dolls, naked and tarnished, trapped in the sheer black stocking of each of these performers. If one were to squint, a rather gruesome picture of protruding skeletal structures of the calf muscle would appear—a disorienting illusion of more-than-human body parts. Each toy would eventually be ripped out from the stocking by its respective hosts in attempts to free themselves of the restrictive prosthetic.

The bearers of the two light sources in the beginning, Yi and Yongbeen Kim, come together in an interlinked position: Yi continues to hold the two phones in front of his eyes as Kim sticks two fingers in his mouth. Relying on the subtle movement of one another, they sync their steps down a long piece of dark brown, matte latex lying on the floor. The crumpled fabric is evocative of the River Styx—a waterway that bridges the world of the living and the dead. According to Greek mythology, a boatman named Charon would ferry souls to the underworld where their fate would be determined. It is believed that the newly deceased had to pay coins for passage, wherein they would generally be placed on the mouth or either eyes of the deceased by the living.

From the flat river of the latex, the four performers break off into pairs. Improvising from Kim’s instructions to lock temple-to-temple, temple-to-shin, shin-to-shin; their movements quickly turn into an asynchronous entanglement. Restricted to maintain contact only between those two body parts, the pairs engage in a wrestle, pivoting their bodies against one another. The aforementioned Kitty has long rope-like hair that takes a life of its own, sweeping the bare ground, tangling and artfully entrapping her opponent in an embrace.

Among the orchestrated contortion of limbs, there is a brief moment when the tension is interrupted. One of the pairs, Kitty and Benjamin Harry Uy detach themselves from one another, allowing room for a new power dynamic to seep in. At his feet and daring not to lean too close, Kitty submissively intakes the changes Uy places in her mouth. Thinking of the coins through the words of Argentine writer Jose Luis Borges in his short story The Zahir, Kim applies a pseudo-spiritual symbolism to the silver object. Here it is the eye, the light, a reward, the point infinitum—and it is consumed.

A new performer, Hanjoo Kim, dressed in a nicely-pressed formal blazer, skirt, and head wrap—all designed by artist and dressmaker Chang Hyun Lee—suddenly charges into the inner ring of the crowd. He proceeds to remove the helium tank from the hook and takes a seat in front of the grand piano. As the rest of the performers remain still, Kim takes a big swig of helium and begins his riff off a melodic motif by musician Jiyoung Wi. Like an orator, he layers the piano variation with his broken voice, crying in English, “Hell is a page / Little lovers / Two heads smiling at my house on glabella (…).” Written by the artist, the words cast the other performers under a spell as they shift their dynamics into a congregation wherein they lie down, shoulder-to-shoulder on the River Styx.

In the finale, the expressionless performers gather around the ‘River Styx’ in an almost mechanical manner. As the helium-filled singing continues, they solemnly proceed to rub parts of their exposed skin with dark honey and feathers. If tarring and feathering was a form of shaming someone for their sins during the Middle Ages, here, the performers dutifully apply these materials of their own free will. The process is conducted with an almost ritualistic intent. From the living to the dead, the animal to the human, the dom to the sub, the sinful to the sinless—in the end, it is only Kitty who remains. From her mouth, coins spill out.

Remnants from the two nights of the live performance, such as clothing worn and objects used, are seamlessly incorporated into the House on Glabella exhibition. Kitty’s hair extension, a long braid, dangles from the ceiling with the helium tank. Large pieces of latex are left tied around columns and wrapped over photographs like a mourning veil, altering the tonal scale of the photographs. Post-ekplexis, the flash of sublimity has passed, and the foreground has been pushed to the background. Transitioning from its position as a prelude to a posthumous ode to the tale of the ‘House on Glabella’ performance, its eponymous show is a performance of an exhibition. **