I tilted over until it becomes horizon is a group exhibition that begins with mumbling if we start at the end. Time and tense already mixed up in the grammar of this title—tilted signaling the past and becomes nodding to the future—I read this collection of works from the present and starting from the back. The concept of the title is a slow leaning I that dips in one direction until it buoys up and tilts to the next, the singular I never standing up straight for long and always in relation to a sprawling and collective horizon. This horizon, a compass of queer elders, kin across human and non-human life, and histories that remain within us, is off in the future—not yet a resting place. The I, not fallen but rather angled, brings in the drift.

The mumble, partially understandable, perhaps completely inaudible depending on where I might be in the gallery, is an indication of the material opacity and illegibility that weaves in and out of this drift assembled by friends and peers Ohan Breiding, Joshua AM Ross, EJ Hill, Abigail Raphael Collins, and dean erdmann. With the help of Director Anna Ialeggio, the works are installed in the String Room Gallery at Wells College in Aurora, NY. In contrast to the mumble, it is a well-lit, white-walled space with windows looking out onto the campus. Yet, natural light is refracted by erdmann’s window vinyls, ‘To Whom It May Concern, dean, after Catherine, after’, casting back dear dedications from queer texts that remain anonymous. Inspired by Catherine Lord’s project at the ONE Archives ten years ago, erdmann takes up the work of queers across generations and illuminates it. One reads, “For my comrades, my light,” just as the sun lands on Collins’s video at different times of day. The video, ‘Dancing with Dead Dykes: Arzner’, homes in on queer filmmaker Dorothy Arzner, who invented the first boom microphone as the industry transitioned from silent film to recording image and sound together.

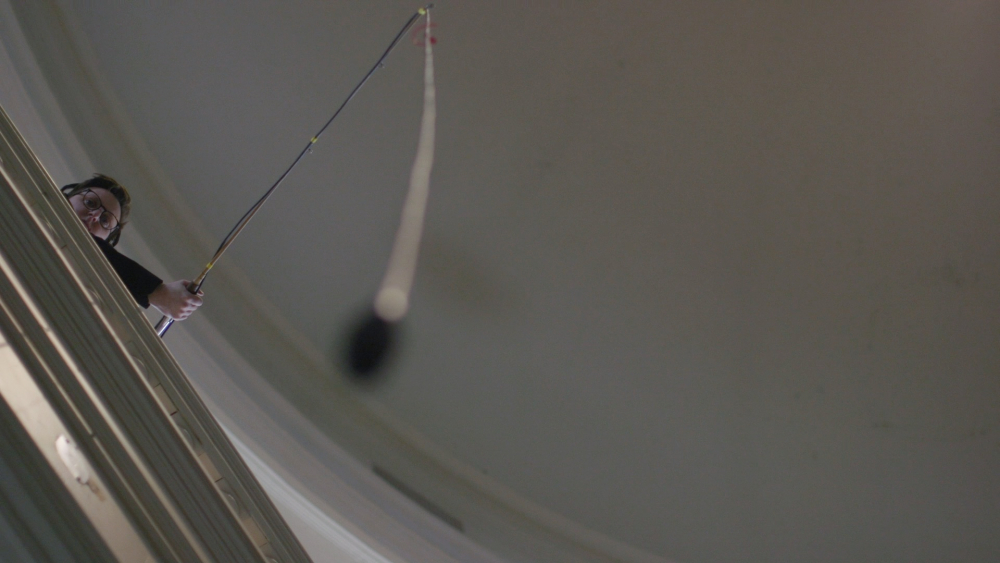

Queer communal filmmaking skips through time in this video beginning with the 1930s, when Arzner surreptitiously kept her screenwriter on set to make last-minute changes without waiting for industry approval and without doubt received feedback from her partner, to 2022, when collaboration is brought to the fore. In one instance, video of Collins’s mouth are overlaid with Joan Lubin’s voice (who authored both Collins’s video script and the exhibition text), mismatching not only sound but also individualized utterance. erdmann also appears beside Lubin, somewhere between a fishing pole and string of audio cable, the first boom. A whisper and a mumble break up the intelligibility of authorship and beget attentiveness—a “listening to images” that recalls Tina Campt’s Black feminist theory and method for approaching the archive. Collins tells me that during this transition in film, the audience was shocked to hear the silent era actress Clara Bow’s voice alongside her image, for it was the same voice they had imagined all along.

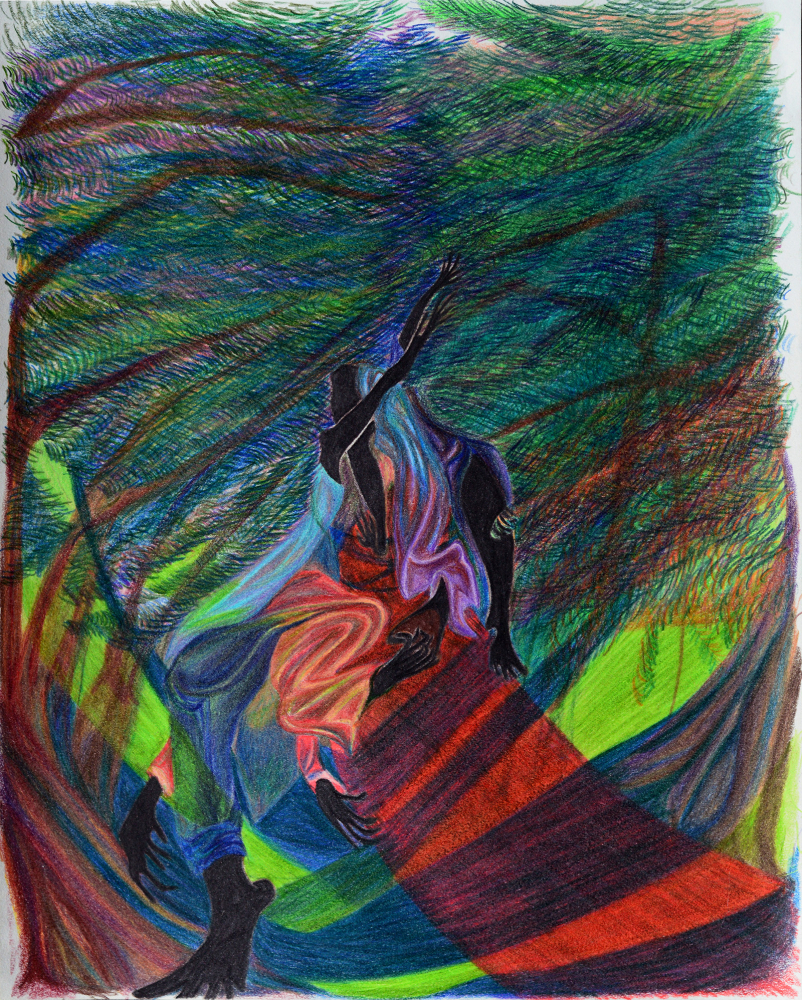

A mumble moves, but not necessarily in a way that is easy to comprehend. Words fade in and out, sound is mixed with language, and micro-movements of the mouth make only barely visible the workings of the tongue and voice. A silent film, or a barely-audible one, gives us the chance to fabricate sound immaterially. Time slows down or speeds up in the mumble, or sounds like language in reverse. This same velocity is at play in the wind-struck works of colored pencil and graphite on paper by Joshua AM Ross. At only a few inches larger than notebook paper, these images pack a whole volume of world in each, complete with billowing clouds, feverish willows, stark contrasting shadows, and thick ribbons of fabric. Weaving in and out of these colored pencil environments are dancing figures with long, outstretching limbs and fingers drawn with a 10B graphite pencil Ross layered himself, one of the softest and darkest grades of its kind. ‘Infinitesimal’ and ‘This way’ showcase the difference in density between these materials, but ‘Porosity’ blurs the graphite with its counterpart, enveloping the body in what looks like dark blue waves of aerated water.

Ohan Breiding’s photographs neighbor Ross’s drawings. This series obscures the faces of queer loves and friends with the use of water, a potentially clear substance made opaque when disturbed. ‘Mother’s childhood pool (Swimmer Series)’ (2018) and ‘Crown: Carry (Swimmer Series)’ (2021) are a pair that connect birth and grief through a symbolic umbilical cord that curls through water and loops through time. EJ Hill’s paintings of flowers in “sissy boy pink” render another type of nostalgia; ‘A Kinder Garden’ is a field of kind, rosy flowers in black outline amongst camouflage-flecked greens, or, if re-written with the German spelling, Kindergarten, a place for children to learn and play. Alongside ‘Green Means Go’ and ‘Seed’, Hill’s paintings invite exactly that: a green light to—in lieu of flowers—send money to the artist for an art school he is building in Los Angeles.

These words, “In lieu of flowers send…,” are scrawled in pencil on the back of every painting, each with different requests. This work is a departure from Hill’s endurance and durational performance practice that undoubtedly takes a toll, such as ‘Excellentia, Mollitia, Victoria’ (2018) where he physically ran around institutions that were violent toward him and other Black, brown, and queer people. With this series, Hill intends to build a different kind of institution and contracts the acquisition of these works to fund it. The inscription remains unrepresentable, illegible, and will not be photographed. Thus, Hill’s canvases exhibit work on two sides: one of which is visible to the visitor, the other made known by word of mouth, and both intended as life-supporting practices.

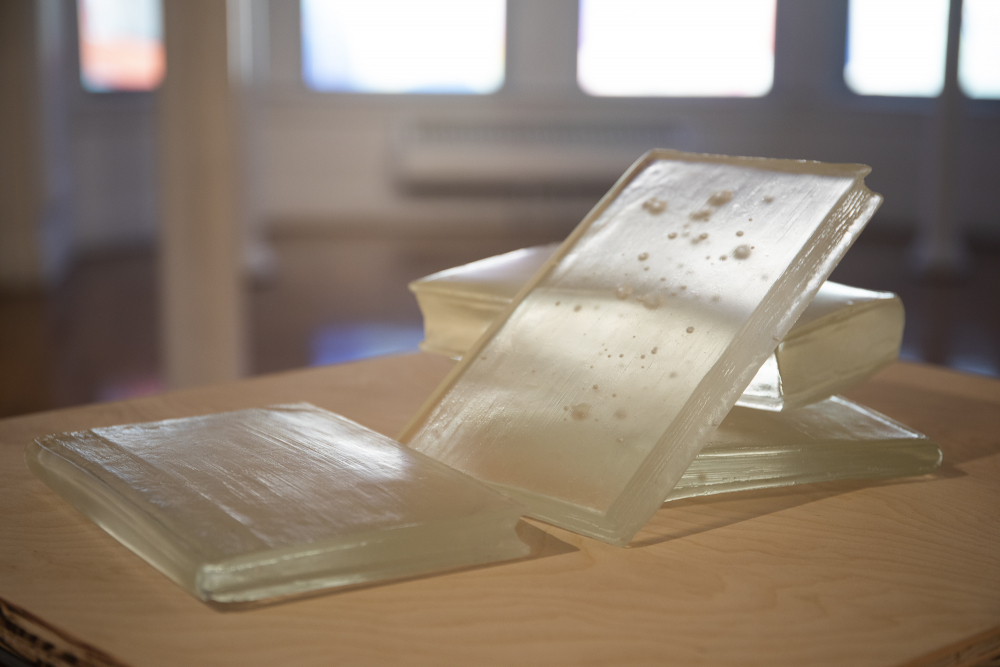

erdmann’s glass books, positioned across from these flowers and made by a process of photogrammetry and casting, are physical copies of artifacts from the Magnus Hirschfeld Institute of Sexology in Berlin, which was devastated by Nazi youth brigades in 1933. The raid destroyed almost all of the library’s collection, but remnants from this significant and complicated institute for the study of queer and trans sexology is slowly being rebuilt by volunteers who rehouse stray books from the institute that evaded the burning. When cast in glass, erdmann’s book artifacts are temporarily hollowed of their written sexologies; the presence of queer lineage is felt—bubbles caught in the glass—but on this occasion they are unaccompanied by scientific classification or prescription.

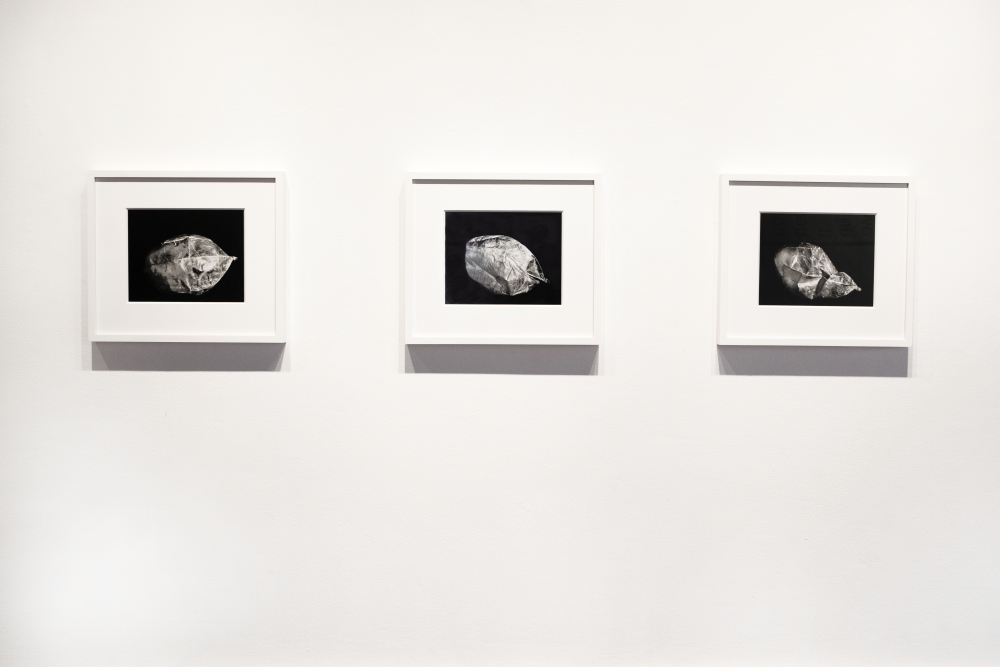

I want to end at the beginning, with the image of the buoy bobbing under and over water, side to side, toppling the straight and singular I. At the entrance of the exhibition are Breiding’s flotation devices, or pig bladders photographed in black-and-white. A technology that dates back thousands of years, these buoys are not anchored, but nevertheless serve as navigation markers for our relationship to rising sea levels and protecting the life that is our fresh- and saltwater. Their photograph, ‘Tōhoku, Japan 2011-Pacific Northwest, USA’, made in collaboration with Shoghig Halajian, pictures a line-up of debris that washed up in Portland, Oregon after the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, organized from smallest to largest. A toothbrush at one end, a large orange buoy at the other. Collaboration and floatation enacted by queer friendship carries this loss across landscapes and through time. ‘Leaking Study #1’ pictures this leaky project—where I is not quite solid, air carries us forward and back, and the horizon catches it all.**