Walking into the small backyard of artist-run gallery Asbestos, an image of a flaccid penis is positioned at the perfect height to turkey-slap a viewer. Titled ‘Spring training’, Tim Hardy’s image for his Helium solo exhibition—running December 18 to January 15—was allegedly developed via two methods: a blow job compilation video and a Salem soundtrack. Witch-house music, fellatio mixed media and, a limp phallus. The sex syllabus of 2021/22? Perhaps.

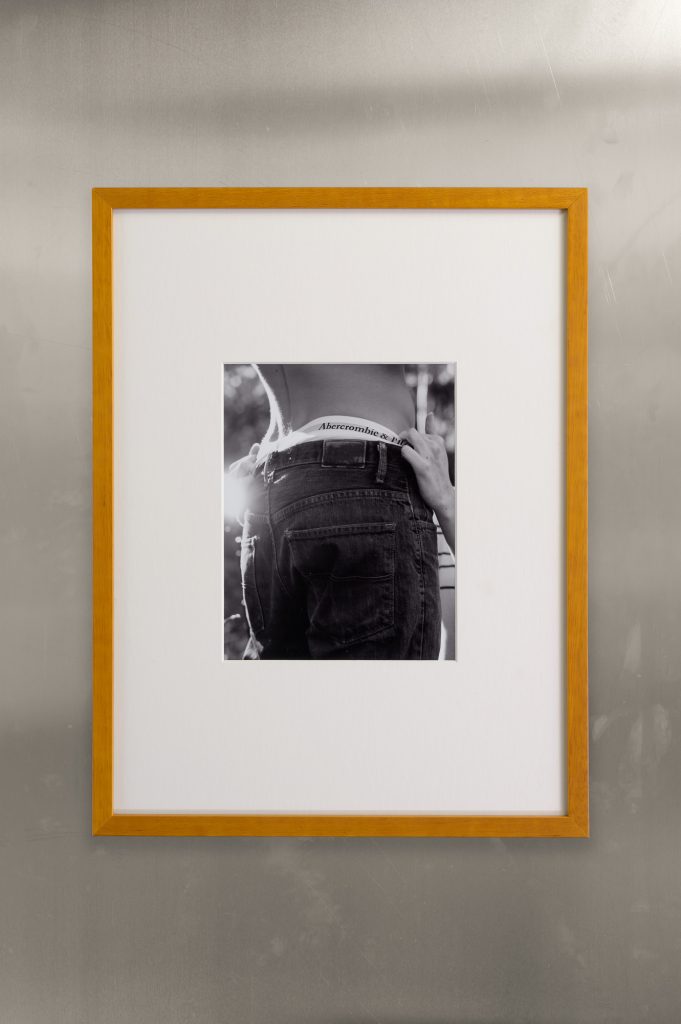

Iridescent, cinematic, and erotic images embellish sheets of aluminium concealing the shed walls of Asbestos. Nine photographs, framed by timber, and approximate in size and position, hang adjacent to one another. Scenes compose themselves in no apparent order. A faceless man lies naked on a velvet couch, a woman stands determinedly guarding his body. Monochromatic hands pull down a pair of Abercrombie and Fitch underwear. Fellatio. Copulating figures are exposed through legs hanging from a car door. An Americana ripped to death model stares adjacent to the camera’s gaze. Dressed in casual wear, his face wears sweat, tears or, cum.

Several shots in Helium bear explicit reference to the 2000s Abercrombie & Fitch advertising campaigns. The infamous catalogues shot by Bruce Weber were known for its casting of American all-star teens, and softcore porn. Viewing the images, one is reminded of the neologism ‘pornoflation’: a concept detailing erotic content is in excess—the power of its currency declining in kind. A Reddit thread lays out how long it would take to watch all the content on Pornhub. Two-point-four million hours converts to roughly 273 years. One in three men, aged 18 to 26, have reported zero sexual activity in the past year. The inverse relationship between increase in porn consumption and decrease in sex is no revelation. Via pornoflation, sex exists in multitudes and yet physical intercourse is declining. How can one represent it when it is simultaneously increasing and diminishing?

Hardy responds by appropriating and inverting the softcore porn aesthetic of his images, and collocating them within the architecture of the gallery. The viewer is exposed to the AB&F logo on white cotton underwear worn by a muscular model. Following the curvature of his spine, their eyes scan beyond the image’s frame down to a cemented trough. The permanent fixtures of Asbestos’ edifice dispense a sheen of grime that arouses the photographic works, paradoxically, seducing more than the sensuous nudity in Weber’s subjects.

The aluminium sheets expose delicate smears of fingerprints. Installed for Helium, the metal is an ode to Wilhelm Reich’s Orgone energy accumulator. A father of the sexual revolution, the Austrian psychoanalyst believed the pseudoscientific technology could cure society’s ills by facilitating sexual orgasms. Here, the metal shields a wall contaminated with asbestos, a fibrous mineral that when inhaled can lead to lung disease. The photographs within Asbestos offer symbolic coordinates constitutive for a perverse, and unknown fantasy: arm and leg warmers, vagina halos, a trough, cement etcetera. The microscopic mineral threatens imposition through abrasion. What fuses sex and asbtesos? An attractive antagonism reveals.

The flesh on flesh in Hardy’s photographs translates to a sexualized presence. Sexual spirituality translates into divinity. The naked, porcelain-skinned woman is titled ‘Fumbling towards ecstasy’. Her legs part over a pool of white light. Angelic in potency, the streaks slash the skin, subsuming her limb and irradiating her stomach to nipple. Behind the frame, habitual exposure to asbestos fibres can lead to inhalation, and when submerged in the lung’s flesh can cause asbestosis. Immortalized sex merges with extinction.

Herein lies the asbestos double entendre: its threat of mortality entraps the projected fantasy cultivated by Hardy’s work, and restricts the full resolution of satisfaction, ensuring objet petit a. An idiom for “object-cause of desire”, it speaks to an inherent antagonism: for desire’s cause is never to reach absolute jouissance, but to continuously reproduce as the symptom of itself. The aluminum walls of Asbestos provide a necessary story to narraitivise a deadlock of sexual drive.

Hardy’s photographic caption ‘Fumbling towards ecstasy’ is a near-perfect analogy for sex. An act of fumbling, a point of distortion, can lead to a rapture where sexuality can be inscribed. The image labeled ‘Teacher’s pet’ conjures a scene. The girl is learning cello, in a bid to entice the teacher, she stumbles on the cords. He sits behind her to correct the posture, while lifting a hand to her breast. In the deliberate mistake, an eroticism takes place.

On the finger-smeared metal walls of Helium, only one face is visible amongst the numerous subjects to hold lustful poses. Sexuality is “in itself grounded in not-knowing”, says Žižek. The unknowability of a partner’s desire forms a gap, wherein lies fantasy. What happens when the other’s desire is laid bare for consumption and mediation? Fantasy diminishes. Two-point-four million hours is 273 years.

The etymology of the word asbestos comes from ‘unquenchable’ and ‘inextinguishable’. The Greek name for a fabulous stone that when set on fire cannot be put out. The enduring quality made it a popular mineral to be woven into the incombustible fabric for housing insulation. Asbestos’ resistant condition is a crucial antagonism to the fantasy in Hardy’s photographs. Fantasy should always be a virtual point of perfection. To resolve is never an objective. The toxic material avows for the eternal reproduction of desire for the subject X by ensuring the fantasy’s illusion. In Helium, sex goes hand in hand with asbestos. Love goes hand in hand with death. Play Salem whilst you go down. The limpness can and will go hard.**