“Please let us rest,” beg the hooves of a galloping white horse in an allegorical poem by Amartey Golding. The London-based artist’s powerful animal protagonist circles the earth for hundreds of years, trampling everything, and everybody, in its wake. A goose that rides with him, trapped and tangled up in its mane, implores, “surely now you must stop”. Later the captive bird realises that the mad steed is driven by fear. Commissioned by Forma Arts and currently touring the UK, the tale is told around a camp fire in the tituar video of Golding’s Bring Me To Heal solo exhibition, currently showing at Glasgow’s Tramway, running December 3 to February 27, 2022. The sequence draws on the fundamentally human tradition of storytelling and mythmaking to create an allegory for the destructive impact of colonialism, white supremacy and capitalism on the planet.

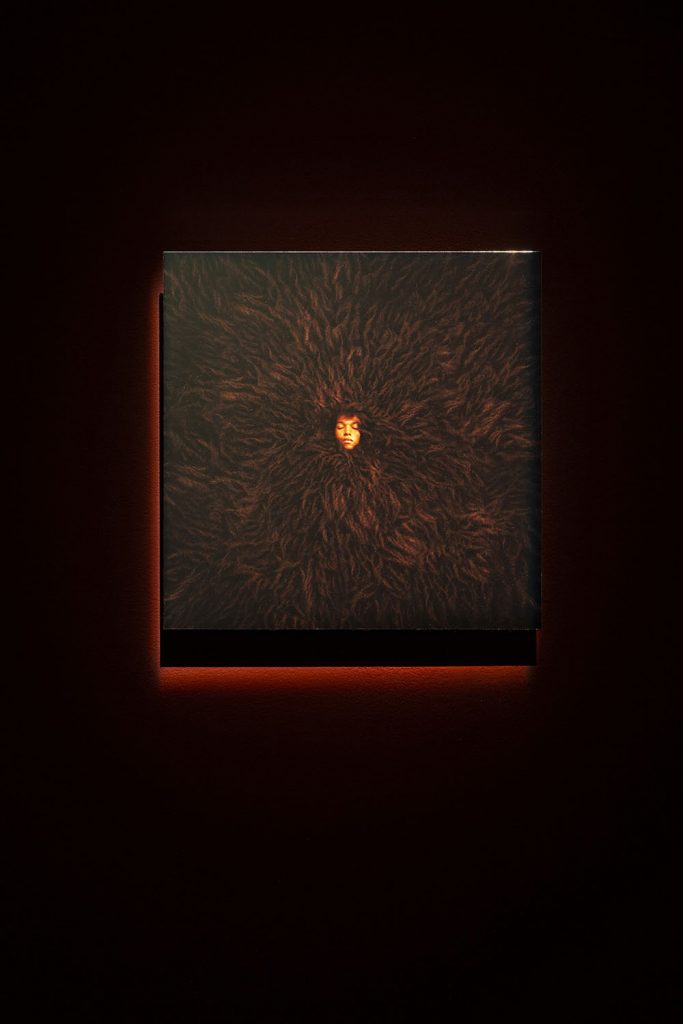

“We’re constantly trying to grab, grab, grab,” explains Golding via video chat from his London apartment, about the affliction of a scarcity mindset that drives so many of us. “I see it as just years of trauma, where, even culturally, everything that we do is about preserving yourself, accumulating and taking as much space as possible because someone else is going to take it.” Raised Rastafarian with Ghanaian and Anglo-Scottish ancestry, Golding’s is a uniquely complex perspective; a subject position which he applies, not only his practice-at-large, but to the Bring Me To Heal project specifically. In the aforementioned video, three men in the English countryside discover a mound of unkempt hair beneath an old oak tree. They proceed to groom and rehabilitate it as it takes a human-like form, eventually becoming a majestic figure, played by the artist’s brother Solomon Golding and called Leeloo. “The idea of that was basically to create a character that could represent the country in one body, one being, and then sit down in the therapist chair and just say, ‘right, what the fuck is going on?’”, Golding explains. The elaborately hand-knotted costume that the Golding sibling wears is made of human hair and takes inspiration for its intricate patterning from Afro hair styles and the body art of early Britons. “When you look at trauma, across generations and individual people and all of this stuff, it starts to get lost. We get caught up in the reality of it, or the hugeness, the vastness of it. We’re so fucking complex.”

Much like the wise Goose of its accompanying fable, Bring Me To Heal explores the space where fear turns into aggression and how cultural behaviours are shaped by trauma. It’s here that the panic of vulnerability is echoed in the Running Horse’s own words—“If I don’t run, I will be run down”—while proposing an alternative path toward healing and care.

**This notion of complexity and mutability—identity and how it’s always shifting—comes through in the work, is this something you personally relate to?

Amartey Golding: It’s hard to know where work starts and where you begin. I think once you’ve made it, at least when I make my stuff, you use it to think about yourself as well. It’s a bit of a tool. It’s constantly changing. I look at all the work that I made in the past, and I’m still being able to use it as a reference and a tool to understand what’s going on. The more different environments you watch it in and experience it in, the more layers get revealed to you.

**When you say you use your practice as a way to explore yourself, it makes me think about the process of making, where you never actually have a clear picture of what it’s supposed to be from the outset. There’s an idea, and then there are other variables which will influence how it turns out. The same applies to humans and their environment, experiences, and the trauma that shapes them.

AG: It’s interesting, there’s the psychotherapy side of things and the cultural side of things—how trauma embeds itself in cultural behaviors. Then you’ve got the epigenetic side of things, where it actually physically alters you. Apparently there are ways to turn that off and turn it on, but it’s still under that banner of healing. It just feels so necessary. Like when we look at so much of what we do, and especially where Britain is, how we relate to it, I just see is a web of trauma, upon trauma, upon trauma.

I was raised as a Rastafarian with the idea of generational trauma, and understanding how the past, no matter how far back it was, affects how you function today, subconsciously and consciously. I’ve been raised around those ideas but up until the past few years, I’ve never thought about relating that to a white context as well, the white British context. With white British trauma, let’s say (it’s a really wide term but conceptually), it’s harder to trace back specific traumas. It feels like there’s this massive disconnect, in a way, than if you are from the West Indies where there’s a lot of historic traumas that you can look at and say, ‘right, okay, I can start tracing this back’.

**It’s more recent history, and it’s interesting what you’ve said about more distant traumas, like the painted people of Gaul who were conquered and colonized by the Romans. That was however-many generations ago but perhaps modern Britain is the outcome of this earlier unfolding of untreated trauma.

AG: Exactly. I think that’s what’s so interesting about this project, is learning from other communities and applying that knowledge, that work, and that vocabulary they’re developing to this context. I think it’s exciting. But also, this idea of trauma, and what trauma does the most damage is interesting.

Dr. Joy DeGruy explains it in such a basic way, that different people get traumatized by different things. We’ve all got different tolerances and contexts. For example, with the Romans and the Britons, it feels like it’s one moment in time but then that has changed the landscape forever, it changes the dynamics. The traumas continue.

It’s just adding a tool to the vocabulary of how we understand stuff, so that in certain circumstances, it can be taken into account. It adds a bit more nuance. At the moment, obviously, things are so polarized, and tribealized, culturally, and I think it’s really interesting when you have an idea, or a thought, or conversation that makes both sides equally uncomfortable.

That’s a core of my practice in general, and this project as well. It asks, ‘who is able to broach these conversations?’ I’m white and black. I’m a straight male. I’m extending that conversation past myself and giving space in a way that’s not expected. I find that quite exciting as a framework for how conversations could be held, if you imagine that people offered things that they were implicated in more, rather than pointing at other issues outside of their control.

The reason I created this garment, was to create a character that for me could represent the country in one body, in one being, then sit down in the therapist chair and just say, ‘right, what the fuck is going on?’ Because when you look at it across generations, and individual people and all of this stuff, it starts to get lost. We get caught up in the hugeness, the vastness of it.

**I was studying psychology a long time ago, and it talked about how social progress is cyclical, and that it goes up and then inevitably comes back down again. It feels like we’re in this moment of entropy right now.

AG: I’m an optimist but I think that if you imagine throughout history—or at least the history that we have access to—I haven’t seen massive opportunities on the soft skills, healing side of things. I see empires as basically trauma responses, like calluses, and trauma isn’t always inflicted by other humans. It could be from a natural catastrophe. It could be from a drought. There are so many things that cause these things. I think this whole project is optimistic because it’s asking and talking about this healing that we need to do and I think it’s possible. It’s not easy but I think it’s possible if we put that energy in the right place and offer space to an exhibition of a black Rastafarian guy who is actually talking about white British trauma.

For a long time, I felt a lot of bad vibes towards whiteness, in my own whiteness. It wasn’t even a conflict for me. I saw it in a very binary way but I’ve now accepted that with my heritage, my ancestry, my epigenetics, all of that stuff, I’m fully white as well. It changes the script, and it’s quite exciting to be able to do that and extend that compassion to a group that are actually still very dangerous.

The optimist in me is just, ‘where has there been a healthy space to explore this?’ because a lot of white people, British people feel the pain they feel and they don’t know where it comes from, necessarily. But they feel the vulnerability, they have the issues and if they had a space to explore it in a healthy way, it wouldn’t be so poisonous and potent.

**That makes me think about white supremacist aesthetics—bland, boring and violent—and how it speaks to supremacy and power but also vulnerability and defensiveness.

AG: What’s interesting is looking at that rigidness, staleness and the lack of acknowledgement or manifestation of emotional intelligence. If you’re talking about that aesthetic, or that approach—the professional business, Imperial approach—it’s devoid of emotions, and feelings, and spirituality. It’s got that naivety but also that power behind it, which I think is quite scary. For me, when I see people like that, or that aesthetic, I just think ‘trauma’.

I don’t believe we have to be inconsistent. I really feel like once we get the right approach, we can extend compassion to everyone and manage it healthily. Everything is interconnected because how is everyone going to heal when there’s one sick person still left in the room in the corner, stinking everyone else out.

**There’s a strong sound element in your work, what is it about music that attracts you to it as a material?

AG: My biological dad was a Pan African musician. He was part of a band called Adzido, who were the biggest Pan African Dance Ensemble in Europe. They would have all of the traditional songs and stories of all these different African tribes and they would keep that alive, so that was one of my earliest memories. My stepdad was a reggae musician and up until he died, he was still making music.

It’s like everyone’s relationship with music, it’s hard to explain. I think it’s the same with my work. I talk a lot, so you’d think that it’s actually more theoretical but my work is actually all about emotions, and creating an environment. Music is about the things you can’t quite sum up into words and it requires you to just submit and explore it in a different way. That’s what I like about art as well. We can talk till we’re blue in the face but really, there’s something that if you sit there and you open yourself to the art. It can do something that we can’t do just talking here.**