For whatever reason, it feels as inappropriate to call Sophie Friedman-Pappas’ recent body of work ‘sculpture’ as it does to call it what it is (‘waste’). Neither designation seems to have much impact on the nature of the miniature conglomerates at New York’s Alyssa Davis Gallery: pocket-sized architectural figures, model landscapes of ecological ruin; found objects, rendered foreign. These images seem to intensify the heatwave outside. On visiting Friedman-Pappas’ exhibition in early July, I stuck around for longer than I’ve ever spent in an art gallery without getting paid to be there: the shadows cast by post-consumer waste and organic detritus, placed on rounded plates blooming with iron oxide, inadvertently function as a sundial would. These post-industrial rock gardens give off an effect that is somehow very zen, and also vaguely horrifying. How long was I there? Thanks to the well-curated library that scaffolds the work—compliments of both Left Bank Books and also the artist—I’d say probably around six hours. Integral in formalizing the Friedman-Pappas’ post-aesthetic, post-apocolaptic imaginary is Moira Sims of Octagon. Titled Transfer Station and running June 12 to August 29, the exhibition appears to contain the entirety of the Anthropocene within it.

Transfer Station not only feels like a seminal exhibition for one of the few, consistently conceptual spaces for experimental sculpture in New York, but sanctions Octagon as an exciting new curatorial platform for work that seems to exceed the traditional formats for the presentation of art. There’s something new here, though not entirely unfamiliar: Friedman-Pappas works within an environmental context I’ll identify here as a ‘post-consumer practice’. At stake here is the concept of the Anthropocene: a conception of geologic time that refers to the irrevocable impact of human activity upon the climate and environment. One could argue that to conceive of the world before and beyond the human changes the nature of the real, at least philosophically. Ambiguous in its totality, Friedman-Pappas’ work exploits both the transitional nature of the “found object” as well as the problems invoked by the emergent discourse of speculative aesthetics.

Alex Garland’s 2018 movie Annihilation might be of some relevance to Friedman-Pappas’ ‘xenocological’ worldview. The prefix ‘xeno’ is Greek and refers to ‘outside’; sometimes translated to ‘alien’ or ‘stranger’: a ‘xenocology’, therefore, is an ecology of an outside so outside it’s virtually unimaginable. The setting of Annihilation represents such an outside, and so do Friedman-Pappas grotesque landscapes. Garland’s film takes place in a biozone known as ‘Area X’: a synthetic biological entity that’s metastasizing throughout a Florida swamp. Whatever ‘it’ is—natural, artificial, alien, divine—‘it’ is selfsame and other. ‘It’ is infinite expansion and infinite reproduction infinitely refracted. Of the scientists that venture into ‘Area X’, one gets eaten by a bear who rapidly mutates into the fear that it smells; another decomposes into organic matter; another sees his organs spliced into a lichen colony after presumably drinking pool water. Beneath the layers of CGI that are the human condition, one begins to grasp Kant’s nightmare of pure reason. Or: Friedman-Pappas’ tiny dolls stroller piled with dead bees atop a pile of rawhide, titled Spotted Cake Topper. Lit with an electric candle, it’s a caricature of Enlightenment:

“… it would still be possible that there be an infinite multiplicity of empirical laws and such a great heterogeneity of natural forms belonging to the particular experience that the concept of a system according to these laws must be totally alien to the understanding, and neither the possibility, even less the necessity, of such a totality could be conceived.”—Kant, Critique of Judgement

“It’s not like us… It’s unlike us. I don’t know what it wants, or if it wants, but it’ll grow until it encompasses everything. Our bodies and our minds will be fragmented into their smallest parts until not one part remains.” (Annihilation)

Watching the art world adapt to crisis is interesting, though arguably not as interesting as the work that’s emerged from it. Yes, lately there’s a lot of painting, figuration, multiples, but Friedman-Pappas seems to deal with much higher stakes than anything the market can neutralize in an installation shot scaled to screen flow. The artist renders the contradiction of the ‘wasteland’ both as an environmental concern that is very much Real (despite its inability to be observed as anything but an aggregate of effects) and also one that’s undeniably alien. These obsessive corpses or corpuses, all in various stages of composition and decomposition, seem to belong to the nowhere that is everywhere. The viewer can only assume ritual causation. Otherwise, the kind of malignant ‘refraction’ similar to that which plagues ‘Area X’. What lies atop Friedman-Pappas’ roundtables is a sculptural narrative of ‘reclaimed land’, a term that reflects how cities would like to imagine their landscape, more and more of which is being built on top of waste. Placed rhythmically across Davis’ triangular shaped floor, the agglomerations of detritus held together in space by artificial sinew, layers of hide glue, static electricity and landfill beg the question of what an ‘object’ even is, as even the ‘found objects’ do not resemble anything yet manufactured. Most importantly, the question that arises is something like, ‘is a pile of waste (such as a landfill) a site or a situation, an object or a space?’ It’s as if Friedman-Pappas is trying to hold all of post-consumer society in the shard of a Burroughs cut up.

These assemblages of post-consumer waste seem to reinforce the household gallery, but this is less visual than it is felt. Since 2015, gallerist Alyssa Davis has quietly sustained an exhibition programme out of her home in the longstanding (albeit dying) tradition of the New York apartment gallery. Located on the eighth floor of a condominium building in the West Village, the gallery evokes a similar intimacy and autonomy as now-defunct artist-run fixtures such as Silvershed or Old Room. What’s new here is how inhabitable a place that functions as both an institution and a living space can be. Davis worked with Houman Farahmand and Aran Simi on the interior design to arrive at a cozy, no-frills space for tablework and comfortable reading that unfolds into the viewing room and that affords a sightline of the work while seated on the couch. “The lobby has been introduced as a space for people to stay longer when they come to see shows, so it’s not just a walk-through,” Davis tells me, adding that any visitor to the by-appointment-only gallery is welcome to stick around and read for as long as they like.

The two variables—including Davis’ new reading room and a rewarding extension of the 15-minute-average walkthrough into the space of an afternoon—give Transfer Station a sense of interminable proportion. The exhibition takes its name from the temporary waste management sites that play a role in the ‘life-cycle’ of municipal trash, which could be said to handle the following: human and animal forensic remains, irrevocable environmental damage, object oriented philosophy, the movement of millions of tons of refuse through New York’s waterways by boat, Amazon packaging, and the longterm impact of New York City ‘master builder’ Robert Moses.

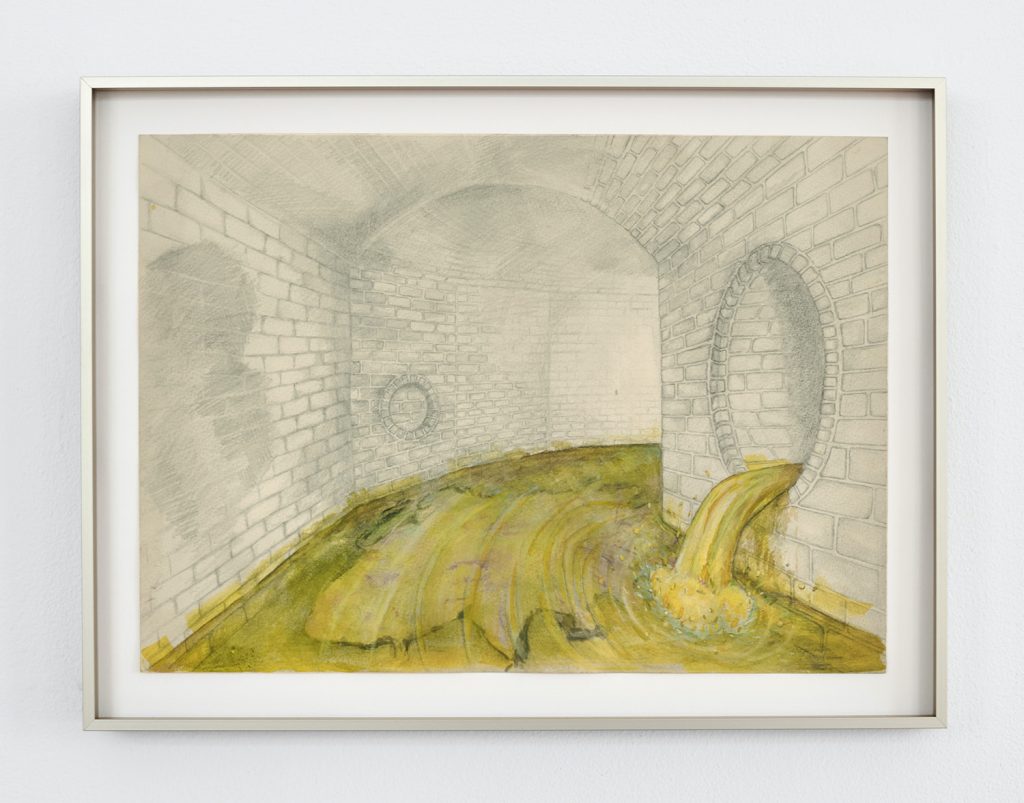

Friedman-Pappas’ two and three-dimensional renderings project into infinity a city laid to waste. On the walls of the gallery, a series of drawings utilizing the dialect of the architectural proposal drawing render the logic of urban development ungraspable in terms of either the territory or the map. The cement plates are scattered rhythmically across a room flanked with windows; mounted at varying tabletop heights, one might recognize beneath the plates those terrazzo planters ubiquitous in urban plazas since the 1980s. And, as with any memento mori, such scenes would be unremarkable were it not for the aura of putrefaction that surrounds them. Hide glue derived and concocted from dog chew toys the artist purchased from Pet Co, synthesizes in the heat. The work on display is as fixating as it is impossible to retain a recollection of in fixed image, which should be apparent in the artist’s effort to stabilize their forms. For this reason, they repel any categorization save for that of the ‘real’. A slightly sweet odor rises from the work.

Alyssa Davis Gallery, as a context for experimental exhibition, makes Friedman-Pappas all the more fitting an artist to inaugurate the transformation of its front exhibition space into a library. The documentation accompanying Transfer Station can barely accommodate the media attributed to a single miniature. Should the gallery be the kind of enterprise that makes use of wall texts (it isn’t), these would read like concrete poems chock full of artificial ingredients: phragmites, saprophytic fungi, penicillium mold, dried rawhide, hand-dug clay, new urban soil, a broken diorama, wood from Noah’s Ark toy, pine rosin, artificial caviar. Then, there’s the soil, the organic matter, and the potters graves rumored to be beneath the One Chase Manhattan (now 28 Liberty) corporate plaza, built in the 1960s.

As of now, Friedman-Pappas’ post-consumer practice orbits the ‘site-responsive’ project for the Freshkills Park Alliance (FKA) the artist underwent in 2019. At the center of all of this (if the Anthropocene can be said to have a center) is the Fresh Kills Landfill. Capped in 2001, this landfill, as the city would have it, no longer exists. But the site on Staten Island designated as a dumpsite by Robert Moses in the 1940s became, just a decade later, so massive that only the Guinness Book of World Records could hold it. By the 1970s, city developers were referring to the landfill as ‘landscape sculpture’. Today, the 150 million-ton pile of industrial waste is twice the height of the Statue of Liberty. Now sealed beneath an “impermeable layer of plastic”, Fresh Kills is both an adversary of Anthropocenic time as well as its icon. By incorporating materials from the 2,200-acre proposed recreational site projected to open as a park in 2036, Friedman-Pappas successfully extends the ontology of the artificial into the aesthetic domain of site-specific installation.

Because Friedman-Pappas is both a New York City native and an alumni of the Freshkills residency program, the local context of the show is undeniable. Yet this ‘locality’ is debatable. During the 2017 edition, artists Joe Riley and Audrey Snyder identified ninety-seven transfer stations across the U.S. that receive and process New York City’s solid waste. Like Friedman-Pappas’ endeavor, this was a research-based project on the part of the artists to visualize the material histories that lie beneath both the actual ground and the urban consciousness. When does something become trash—as opposed to a ‘found object’; as opposed to an artwork—and under whose authority, or authorship, does it fall? To incorporate waste into an artistic practice is to engage with the problems of 20th century art, and also the crisis inherent in a 21st century worldview.

It would seem that the amount of language it takes to process a piece of garbage is comparative only to that required to process a piece of art. As with anything taboo, the waste network relies on euphemism. Fresh Kills is not a dump, rather, it’s ‘reclaimed land’. This is visible both on the part of the private corporations that the city contracts to manage waste, as well as recent artistic engagements that, if nothing else, aim to make the waste cycle legible. Riley and Snyder’s stop-motion ‘portraits’ of the ‘wastestream’ chart what they understand as a “displaced burden of sustainability” (i.e., what the public knows only as “someone else’s job”) by activating the language around trash: toxic debt, negative commons.

To use Fresh Kills as a medium is complicated, but to regard it as a ‘site’ is impossible. You can’t see it, you can’t enter it, you can’t even, really, get close to it. The best you can do is stand on top of the layers of soil that conceal it and count the methane pipes popping out of the ground between flurries of wildlife. Friedman-Pappas reflects on these visits with a tinge of irony: “Gassing masses is not what they’re advertising. The staff at Fresh Kills runs a strategic campaign to highlight the repopulation of animals in the park, and to downplay the presence of waste. My site visits would consist of Freshkills Alliance employees pointing out and exclaiming, ‘An Osprey! A Red Fox!’”

A current of surrealism necessarily beats through the ‘site-responsive’ projects that emerge from the Freshkills program, and from post-consumer practices at large. What Friedman-Pappas uncovered over the course of her residency was not only a narrative of New York City’s century-old battle with public space and household waste but the radical alterity inherent in a world whose future seems as uncertain as it does hostile.

Friedman-Pappas is amongst a generation of artists for whom both nature and futurity evoke crisis—environmental crisis, ontological crisis—and who are decades divorced from the Earthworks movement. Yet she participates in a long, and recently revived, legacy of efforts to produce work on the scale of environmental impact. These approaches have, historically, tended to occupy three different camps. There are the naturalists, for whom the landscape resembles the thing to which it points, an outside that stays put even as it evolves. The second approach is elaborated in Robert Smithson’s Tractatus “The Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects”, which accompanied an artistic interest in site, place, ruin, prehistory, geologic time, landscape and industrial machinery during the 1960s and 70s. Smithson preferred the term ‘abstract geology’ to ‘land art’, but in each case, sediment wins out over semantics: “The manifestations of technology are at times less “extensions” of man (Marshall McLuhan’s anthropomorphism), than they are aggregates of elements. Even the most advanced tools and machines are made of the raw matter of the earth.” The earth, like language, is understood as a system.

The third approach to land-based art is exemplified by the Freshkills Park Alliance artist-in-residence program, which is framed like an research and development exercise; a means to incorporate artists into the decades-long city initiative to ‘reclaim’ the landscape. “The transformation of what was once the world’s largest landfill into a sustainable park makes the project a symbol of renewal and an expression of how we can re-imagine reclaimed landscapes,” the FKA’s website reads. “As more sections of the park open, the unusual combination of natural and engineered beauty—including creeks, wetlands, expansive meadows and spectacular vistas of the New York City region—will be accessible.”

There’s an irony to Friedman-Pappas’ miniatures, and also a critique. Before one assumes that the tiny size of her sculptures are a solution to the quarantine that severely limited the spaces through which artists could work (even if it did exponentially extend the time one has to make art), they should think, ‘miniatures, ‘minimalism’. The diminutive post-human landscapes beg the question of whether or not Michael Heizer’s $25M monument to institutional privilege, ‘City’, is, in fact, a ‘minimalist’ gesture. When Heizer left the city to begin mining and pouring cement at a post-nuclear testing site in the Nevada desert, the land artist might as well have dropped off the planet. Forty years later, his platonic urbanism is best captured by Google satellite, in images that reveal massive forms suggestive of a mini-golf course for aliens. “I’m building this for later,” Heizer stated of ‘City’, which upon completion will be the largest sculpture in the world. As of yet, ‘City’ contains no litter, but Friedman-Pappas assures us that it will. And she is, technically, working on a much larger scale than Heizer. Freshkills park is three times the size of Central Park, whereas ‘City’ is barely the size of the National Monument.

“Size,” Heizer maintains, “is real. Scale is imagined size.” When Friedman-Pappas makes passing reference to the human and animal forensic material possibly detectable in her sculpture—plastic bags, elevators from the Twin Towers, unidentifiable human remains, police cars—what comes to mind is the scale of New York City’s greatest disaster. Some have referred to Fresh Kills Landfill as “our generation’s Ground Zero”, however, this comparison feels inappropriate if only because Fresh Kills contains Ground Zero. Just a few months after the landfill closed, it was reopened as a sorting ground for roughly ⅓ of the rubble. Over the next 10 months, 5,000 human remains were uncovered; out of this, only 300 could be identified.

From this angle, the work of the Freshkills residents make an artist like Heizer sound delusional. “I’m interested in making a work of art capable of representing all the civilization to this point”, he explained, when prompted as to what motivated him to create ‘City’. But if size matters so much, then Fresh Kills is undeniably bigger. As an aesthetic object, it’s scaled to the 20th century. When, in her artist’s statement, Friedman-Pappas makes reference to “what lies beneath”, what lies beneath is as unknowable as what would compel an artist to tan leather with her own urine. The process features distinctively in a drawing, ‘They Spoke of this Fruit with Grimaces of Disgust’; the sheep hide itself is incorporated into ‘Hide Pile’, a tiny sculpture that rests upon one of the tables.

Here, process and product descend into both madness and ambiguity, for the resulting forms render that which cannot be observed. We are talking about the art world in the 21st century but we are also talking about an object that cannot be photographed or seen from any vantage point, despite rumors of having been observed from space. It’s an object that burps deadly methane and that happens to be covered by an ‘impermeable’ layer of plastic; an object that is not alive but has as many past lives as layers of sediment; an object that is not a work of art but is capable of representing all the civilization to this point. In other words, we are talking about creative surplus.

Is the object that Friedman-Pappas approaches as her medium one that exceeds its material reality, in much the way a city—defined by its people, its epoch, its infrastructure—exceeds the hollow, architectural shell of a city? Unlike the modernist land art project, art after the Anthropocene is puny: Friedman-Pappas’ ‘One Chase Manhattan Plaza’ features a translucent dome made of glue bubbles as a skylight, evocative of the strategic concealment that motivates urban development budgets. Proponents of object oriented ontology would argue that the building Friedman-Pappas assembled out of bricks made from Fresh Kills topsoil and animal-derived glue isn’t an allegory for the city, it is the city—the same way that the skyscraper it ‘represents’ isn’t an allegory for financial dominance, but is that dominance.

Following her year-long residency, Pappas-Friedman returned to her Financial District studio in the apartment also utilized by her mother, a painter. As Byzantine as the images she renders are, there’s a dimension to her practice that can only come from a New York native. Her intention “to pull the pants down on the landfill’s covered propriety”, as she writes in an artist’s statement, is undoubtably personal. Yet, Friedman-Pappas’ poetic and subtly surrealist approach to aesthetics after the Anthropocene renders this task less like the post-human version of The Emperor’s New Clothes than it does this scene in T.S. Eliot’s 1922 poem ‘The Wasteland’:

“That corpse you planted last year in your garden,

“Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?

“Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed?

“Oh keep the Dog far hence, that’s friend to men,

“Or with his nails he’ll dig it up again!”

In other words: what is buried cannot be discarded. Still—for a room full of garbage—the feng shui at Alyssa Davis is great. The ancient Chinese art of deciding where things go is speculated to have initially served the purpose of spatially distinguishing “the bed from the dead”, not according to what was symbolized by sleep or the afterlife but according to the laws of nature. The Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong, for example, has terrible feng shui. To offset its negative energy, developers were forced to build out the plazas that surrounded I. M. Pei’s skyscraper with rocks big and ancient enough to keep the ‘knife-like’ edges of the building from undue influence.

For Friedman-Pappas, not only is every object of culture an object of barbarity, it’s barbarity is what makes it natural. The city she renders in Transfer Station thus becomes a poetic economy of non-human, post-human, and non-, as foreign as it is ironic. Because the Modernist project cannot contain the Anthropocene—unlike the Anthropocene, which has the unusual capacity to contain both itself and its false consciousness without imposing a limit on either one. In the drawing ‘Big Fish Eat Little Fish’, Friedman-Pappas proposes an architectural intervention on the part of the autonomous agency of a sunken ship so swollen with leachate that it absorbs the bank building its pinned under. The ornamentation follows suit when gargoyles and/or the vermin of the built environment slowly consume the fixed coordinates of the International Style—the architectural movement the Chase Manhattan Building made canon.

Like value, trash is a denomination. Ontologically, it is negative surplus. Sculpturally, it’s undeniably a positive process. Recent efforts on the part of artists attempting to work at non-human scales have required an aesthetic vocabulary equipped to deal with post-futurism. What these approaches have in common is that they seem to incorporate an ironic distance, a means to deal with the apparent ‘lawlessness of matter’ (Kant) without getting mixed up in it. Science fiction writer J. G. Ballard picked up on the logic of aesthetics after the Anthropocene well before post-humanism entered the picture. “We’re now completely surrounded by artificial environments,” Ballard said, in his campaign against fiction writing. “the role of the author now is to create realities, or to discover realities perhaps.” To pull the pants down, as Friedman-Pappas would put it.

What’s funny about this is that land art, today, is no longer distinguishable from institutional critique: in what sense do efforts to expose the real necessitate its translation into a pre-constituted worldview? The question of “does it solve anything?” obviously comes to the fore when attempting to interpret an artistic practice scaled to environmental impact. An aesthetics after the Anthropocene is one that answers this question by pointing its mutated talons toward problems bigger than humans are capable of having, as the ground rises up from beneath.**