Last year, New York-based artist and content producer Joshua Citarella posted a meme of himself on Instagram wearing a US military uniform and an eye patch, a cigarette hanging from his lips, clutching two children. “My account is now shadow banned and has lost 75 percent of its reach,” the caption reads. “I do not yet know how long it will last. You can hit the bell to enable notifications, or archive a few of my posts to reprioritize the feed… You can find me elsewhere on Twitch & Discord.” Shadow banning, also known as being de-prioritised or de-boosted, is when a user’s social media account is intentionally limited in reach and visibility.

Citarella is known for his research into online political subcultures. In 2018, he published ‘Politigram & the Post-left’, a publication and online pdf that catalogues radical Gen Z content and postulates how social media shapes the political ideologies of its users. He coined the portmanteau ‘Politigram’, to encompass political radicals he has encountered on Instagram. “At the time, my interest in exploring this space was to find an online left that can compete with the social media impact of the alt-right,” writes Citarella in the pdf. “My practice became an extensive research project into the underbelly of online radical groups.”

Part of the artist’s investigation includes the emulation of a recruitment tactic he adopted from these sorts of Instagram accounts, some of which are documented in ‘Politigram & the Post-left’. For an estimated six weeks, Citarella engaged in a strategy where he posted between 30 to 40 Instagram stories per day. They took the form of memes and denoted various ideologies from the political left, right and centre, and referenced cultural theorists like Mark Fisher, Nick Land and Slavoj Žižek. “I wanted to show people politigram through my feed and this was a strategy to get a specific type of traffic to my account to help promote my podcast,” writes Citarella on the live streaming hub Twitch, where he debunks political and cultural content for around four hours every Monday. “The month I became shadow banned occurred directly after I turned down my last freelance jobs from clients and friends I had for years, and all of a sudden I had no visibility so I took that very seriously.”

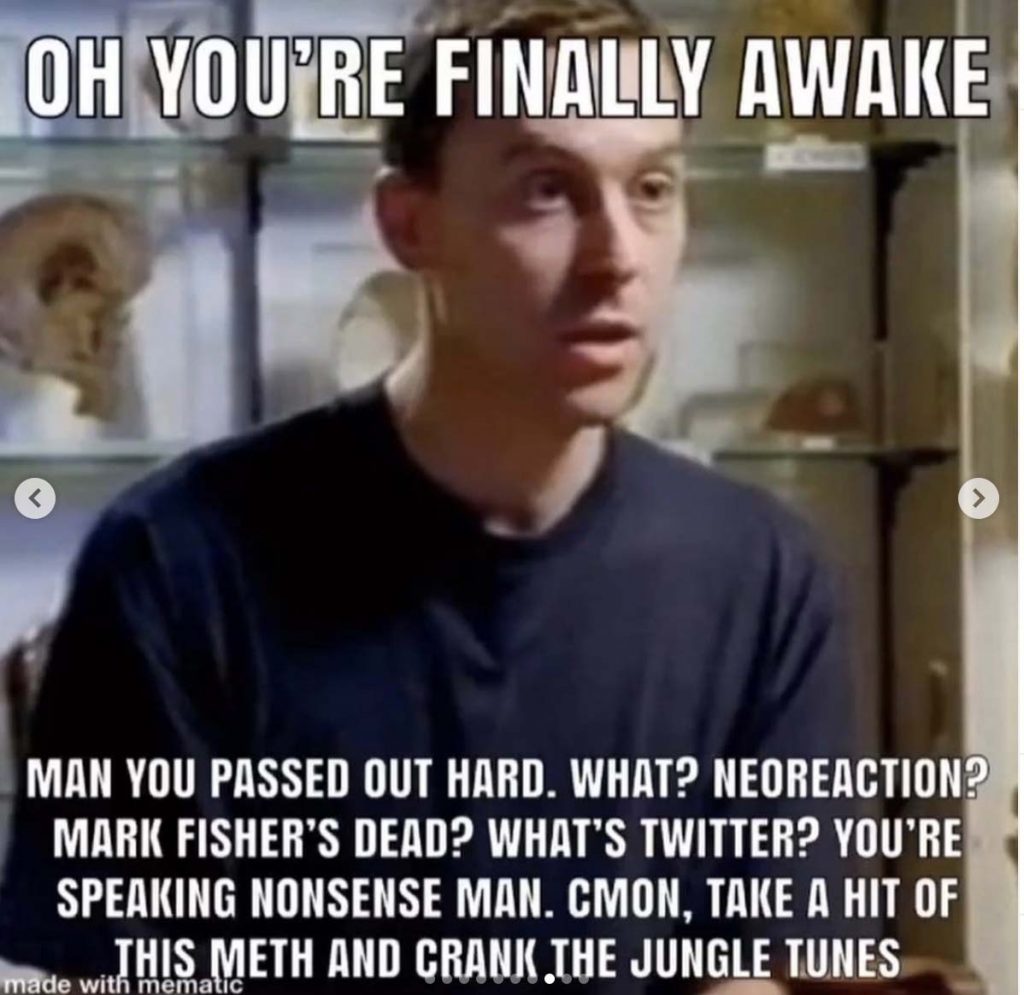

Citarella’s memes are saturated with irony and often labeled as ‘shitposting’, a term used to describe ironic, aggressive and troll-like social media engagement. They can also function as a symbolic mirror to the complex intersection and behaviours of technology, culture, politics and theory. Take as an example the ‘You’re finally awake’ series that went viral in September 2020. The format plays with the viewer’s chronological sense of time, transporting them backward or forward by referencing past events, or accelerating current ones to predict the future. One image in the series features reference to philosopher Land’s Dark Enlightenment theory, Mark Fisher’s tragic death, and jungle music within a 50-or-less character count. A sense of illusionary escapism is projected with the second-person tense and interrogating question marks. As Citarella outlines in the caption: “it’s almost like people wish we could escape our current timeline.”

Sharing political content, like the fake replica image of the Boogaloo Boys Gen Z Civil War nostalgia militia group, can come with consequences. The alt-right uniform is ironically exhibited with the styling and placement of the popular and well-known Supreme and NASA logos. Citarella presumes posting content along the lines of the former resulted in a shadow ban.

The undetermined definition of a shadow ban

The function of ‘shadow banning’ is a result of the platformization of society—the transition of communication onto digital platforms. The Terms of Service (TOS) differ between these applications and communities, and remain in a state of flux due to constant technological updates. A shadow ban can be seen as a discrete form of censorship, where an account is not deleted but the visibility is considerably reduced. It’s unknown what exactly triggers the ban, most likely it’s caused through a repeated accumulation of tacitly proscribed content.

So far, shadow banning is unprovable apart from anecdotal reports. Instagram’s TOS contains a slither of a reference to what it could entail, where the opaque community guidelines mention that posts may not directly breach their terms, they may “not be appropriate for the global community”. In these instances, Instagram will “limit the posts from being recommended on Explore and hashtag pages”. It should be noted that platform behemoths like Facebook, Twitter and Instagram have a crucial liability in moderating the spread of legitimate harmful content. However, it’s obvious the examples in this text don’t fall within the extremist content category.

One presumed effect, as described by Citarella, is in a user having to type the full name of the shadow banned Instagram account before it shows in the auto-populated dropdown search box, a tool to aid in finding profiles. “Another level [of censorship] is when you have constantly reduced traffic,” he adds. “My traffic didn’t reduce by 50 percent, it reduced by 99 percent for two months.”

The concept of shadow banning came to fruition in 2018, with a widely circulated Vice article, which claimed microblogging network Twitter limited visibility of prominent Republicans by removing their handles from the drop-down search box. Shadow banning was then coined by then President Donald Trump, who accused the microblogging service of restricting his account in 2018. The New York Times defined shadow banning as when users’ posts become invisible because they are “algorithmically shut down”. Since the Facebook conglomerate—which includes Instagram, Facebook Messenger and Whatsapp—offers no substantial definition that explicates the practice, anecdotal examples are the only evidence.

Real-life effects on art practices & audience engagement

For a murkily-defined term, the influence on users’ accounts can be exorbitant. Citarella earns a living through Instagram, so he tracks his engagement closely and often relies on analytics to understand audience demographics. On the high end, the artist would generally receive 2,000 views on his Instagram stories. The lower end would track about 1,200 views per story. “I discovered it literally through watching the analytics,” he says, about becoming aware of the possibility of a shadow ban. “It steeply dropped off, really noticeably, from a medium number of 1600 to about 300.” In the midst of the ban, Citarella opened his Left Futures solo show at BFI Miami and published the second edition of his book, 20 Interviews. He promoted both these projects, while reaching less than a quarter of his usual audience. “We haven’t been able to get any press for it whatsoever,” said Citarella about the solo exhibition. “It’s frustrating as a producer because you labour on something for a year—which is a labour of love—and then nobody knows it’s there, except for the same 300 people who can see your stories.”

Los Angeles-based artist and activist Emily Barker outlines a similar experience. Their posts take the form of Instagram selfies, Tweets and TikTok videos, which often feature descriptive captions illustrating the politics and austerity around disability. “I repost about misogyny, police violence, racism, ableism… and what we can do to actively change things, while sandwiching this between cute and funny content,” writes Barker over email. Despite primarily using Instagram for disability advocacy they noticed the stories speaking out against police brutality received considerably fewer views, compared to other more ordinary content. When asked why they suspected a shadow ban, Barker recounts friends and followers messaging them to say their posts were no longer visible. It should be noted that Citarella’s and Barker’s descriptions of the ban are informal evidence, and they raise questions around the difficulties of relying on human observation to prove technological polarities.

Technology and the ‘Culture of Compliance’

In 1989, during the ‘Massey Lectures’, physicist and author Ursula Franklin examined the impact of technology on human life. She identified two distinct categories of automation: Holistic technologies are associated with artisans, such as potters, weavers and metal smiths, who control the process of their work. In contrast, prescriptive ones order and divide labour around central management. In doing so, the process of work is outside of the labourer’s control, resulting in compliance with the system. Amazon factories, for example, systematize employees around a central management, likewise Instagram could be seen to divide user’s posts with algorithms and TOS.

Franklin refers to the increased dominance of prescriptive technologies as a ‘culture of compliance’, and art and technology critic Mike Pepi elaborates on this concept. In his 2019 essay, ‘Control, Alt, Delete: The New Artistic Activism Versus the Surveillance State’ he writes, “perhaps no technology illustrates this culture of compliance more plainly than the rise of big data analytics”. If the notion of a shadow ban, as described by Citarella and Barker, is in fact a reality, it’s a mechanism that influences a ‘culture of compliance’ by encouraging self-censorship. Put simply, if an artist who makes a living through Instagram is softly banned, resulting in a loss of revenue, they may change the type of work they choose to publish.

Cristine Brache is an example of how shadow banning can cultivate self-censorship. The New York-based artist’s practice includes depicting personal mythologies, analyzing signifiers ascribed to femininity, and alluding to the truth between desires and reality. The pathologizing of emotion and sexuality is a recurring theme on Brache’s Instagram. One series of images depicts Brache in a number of tantalizing poses. The first features the artist topless, wearing a black school-girl overall designed by the Freudian, blasphemy-inspired label, Praying, with the caption, “It’s so hard not to keep my throat from getting parched by praying, a boredom so alluring, it makes people jealous.”

Before shadow banning became a term, Instagram deleted Brache’s account for violating the TOS in 2015. The artist suspects her current account has been shadow banned. It’s impossible to prove, since the artist’s following count tracks below 10,000 and she is unable to see her analytics to gauge user engagement. “I’ve become super careful about what I post,” explains Brache via email about how the initial deletion made her modify her online behaviour. “I can’t comment on how that affects my engagement other than I’ve successfully been censored by censoring my own behaviour.”

Technology arises out of a social structure

The conceptions of data as absolute and algorithms as a consistent regulating system died alongside the utopia myth of Silicon Valley. We know the sorting mechanism of algorithms enforce biases, and when our attention is translated into data, it’s turned into profit. One needs to look no further than TikTok for confirmation of the former. In March of 2020, independent news platform The Intercept published the app’s internal moderation criteria used by outsourced freelancers to censor content. Moderators were instructed to suppress posts of users with ‘abnormal body shapes’, ‘ugly facial looks’ and ‘facial deformities’.

Meanwhile, Barker claims to consistently experience algorithmic bias. They noticed their first videos uploaded to TikTok attracted thousands of views, but after posting one that stated “billionaires are the burden not disabled people” it received below 50. Social media platforms enforcing and upholding systemic oppression is difficult to contextualise when accountability relies on ownership, which itself relies on isolating the individual oppressors. But it’s implausible to isolate individual oppressors when online networks are made up of various entities that produce and circulate content—from moderators, to UX and CX designers, to artificial intelligence. When these systems are made up of intricate multiplicities of human and non-human designed software, the question becomes how can we hold a platform accountable?

As systems advance, the technological solutions for moderating content will become even more complex, and therefore, ill-defined. By not defining shadow banning in the Terms of Service, platforms are being knowingly vague in order to bypass taking ownership for a tactic, which could be seen as restricting free speech.

As Franklin outlined in her lectures, designs of technological apparatuses arise from a social structure, and this should be the focal point when examining emerging technologies. Likewise, Pepi’s mini manifesto ‘Elements of Technology Criticism’ synthesises a set of recurring principals, in order to critique the components of social networking systems, instilled in the design of applications like Facebook and Instagram. “Algorithms are made of people,” he outlines in point nine. “They are editors, they steer and privilege certain values, and are never objective.” As technology develops and censorship increases with the continuous amalgamation of our identities onto a grid, this begs the question, if you haven’t already been shadow banned for what you say, have you been saying anything at all?

Imagining the future in a time plagued with uncertainty

Episode 11.5 of Citarella’s Memes as Politics podcast was published in the midst of his shadow ban. Titled ‘Revolt Against the Big Tech World’, the artist hypothesizes a new era of the internet, one that resembles the Chinese model of social media.When asked over Twitch what his predictions are for the future of online censorship and Instagram in particular, Citarella gives a more modest answer. “I think online censorship is TBD. I think we have to learn some more about what is going to happen,” he says. “[The] general prediction is it will clamp down and become increasingly tighter.”

New York City’s downtown film account, The Ion Pack, reports similar symptoms of a shadow ban. The anonymous Instagram account posts a collection of memes referencing niche films, and video snippets taken from their podcast interviewing underground filmmakers. It’s an unlikely candidate for a shadow ban, considering they post no political content. “We think it might be just from being affiliated with accounts that are posting more political and controversial things,” the anonymous project writes via email. “We once reposted a meme to our story of Vincent Gallo’s dick in Brown Bunny that might have something to do with it.”

When asked about the future, The Ion Pack foreshadows censorship only becoming worse. They predict a bleak setting, where an account will not only be algorithmically shut down for posting, but for searching controversial topics in private bowsers. “I’ve noticed my targeted advertisements are directly related to things I’ve talked about on Discord,” they explain. “It is pretty clear Instagram is gathering your information across different platforms.”

The rise of Discord, Patreon and Substack could be viewed as a retaliation to censorship experienced on mainstream platforms. Citarella refers to the ‘Clear Net v Dark Forest’ model, created and theorised by Carolina Busta and the New Models community. The infographic categorises zones for online platforms based upon the user’s anonymity in the space. Defined by Busta in a widely circulated article for online journal Document, the ‘Clear Net’ includes publicly-indexed platforms, like Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. Here, users are subject to peer and state scrutiny, and can be censored via account deletion, content removal and shadow banning. In the ‘Dark Forest’, the infographic explains, “One forages for content… rather than accepting whatever the algorithms happen to match to your data profile”. These sites include Discord servers, paid newsletters, podcasts and encrypted group networks, like Telegram. Here, content can flow without being subjugated to algorithms and non-chronological timelines. The user can interact with a concealed identity, and their online activity will not impact real-name SEO (search engine optimisation), adding a layer of anonymity.

It’s reassuring to see new online vessels that can act as facilitators of discourse, away from the censorship and algorithmically-driven content of mainstream social media. Yet, imagining a future without Instagram, is almost as hard as imagining a future without the internet. Perhaps, the way forward isn’t to restrict ourselves from platforms like these. Citarella outlines an alternative strategy, where Instagram operates as a phone book in which you find a link in the account bio leading you to a ‘Dark Forest’ space, like Patreon and then onto a Discord server. It’s hopeful to know online spaces exist in which anonymity can be a given, allowing for rigorous conversation, push back and controversy, because it’s an increasingly rare occurence on mainstream platforms today.**