“You mention queer psychedelia — I think psychedelia might be inherently queer,” writes artist Eve Stainton over email, when I ask about this aesthetic notion that permeates their work. “A state of transformation; a non-linear process that can’t be fully comprehended, needing something other than normative programs.”

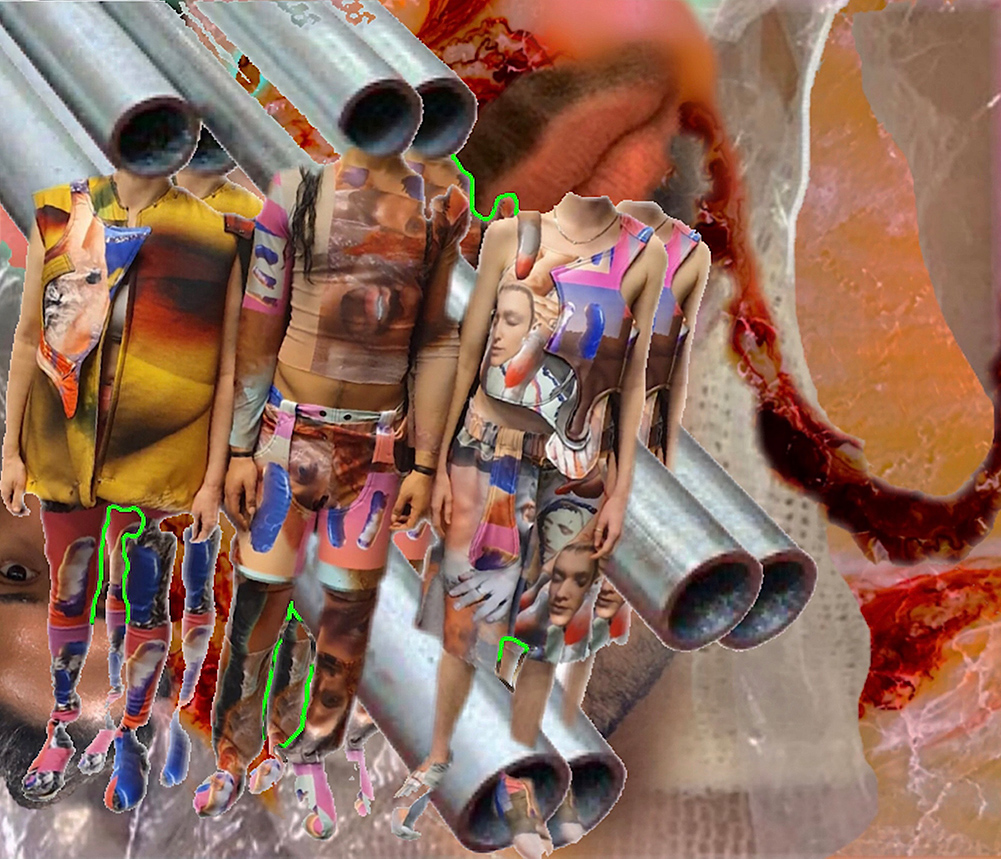

We are emailing in the run up to Stainton’s Rubby Sucky Forge, a performance featuring dance, collagic video, and music by Beatrice Dillon, set amongst steel scaffolding props and premiering in London on October 15. Working across movement practices and digital imaging, Stainton’s visceral body of work explores gender variance and expanded understandings of the lesbian experience. Using aesthetic motifs of horror and digital maximalism, Stainton’s practice, including collaborative projects with Florence Peake, has been seen at the Venice Biennale, Block Universe, NottDance at Nottingham Contemporary and Sadler’s Wells Theatre to name a few.

“Queerness obviously doesn’t always have to look soft and fluid,” Stainton continues, on their creative affinity with the hard edges of metal. Steel materials are used prominently in this most recent performance, which was co-commissioned by the AndWhat? Queer Arts Festival and features collaborating performers Gaby Agis and Joseph Funnell.

A willingness to critically disassemble normative expectations and modes — including tropes within queer communities — runs across Stainton’s work. This comes to the fore as we discuss topics ranging from psychedelia as a site for queer transformation, club spaces and intimacy, to remaining present with sadness.

** I’ve been thinking a bit lately about psychedelia and what a queer psychedelia might be. I was recently discussing the notion with artist Zach Blas on our podcast, and how the term comes originally from meaning “mind-manifesting.” What are your thoughts on queer psychedelia?

Eve Stainton: The idea of psychedelia is interesting to me in a number of ways that all conjure different things. When it’s transferred across into an ecology or language of movement worlds, for me psychedelia speaks to a sense of disorientation which has a shifting image quality and feeling of getting lost. Or knowing this is possible — changing perceptions or an altered state of awareness.

In the work Rubby Sucky Forge, psychedelia is most prominently aesthetically present in the digital collage film work. I’m understanding my digital collages at the moment as science fiction choreographies, to skew or critique an understanding of what is considered ‘real’ or ‘natural.’ For me this lands in dismantling the construct of the gender binary, but also anything ‘manufactured,’ with the understanding that constructs are wedded to whiteness. I’m thinking on a kind of psychedelic horror that can be caused from being in proximity to cold and violent ideological hardness, such as racial discrimination, class discrimination, ableism, transphobia. Psychedelia as a trippy place that maybe can’t be explained, but holds a queer space for transformation. That a state of psychedelic horror might create a momentum where disruption, liberation and change can occur. Or that anger or fear aren’t always bad things.

** Metal as a material plays a role in Rubby Sucky Forge. Can you tell us about your interest in using metal for the performance, any cultural histories you’re evoking?

ES: My interest in metal as a material lands in different places and has been seeping into my life over the last few years. I started to feel a confusing sense of kinship with some of its properties — harsh rigidity, fixed, coldness — which was pretty troubling as someone who identifies as non-binary, queer, grounded in the in-between or shifting metamorphoses. The complexity of this contradiction became interesting and important to unpick.

The metal that is used in the work is related to construction: scaffolding poles, elbow joints, clamps, T-joints, tank traps. There is quite a literal reading of this — constructs, and people in relation to constructs — but I’m also interested in the idea of metal having emotional edges, not being as straightforward as it might appear. We (the performers Joseph Funnell, Gaby Agis and myself) are working with different ‘scores’ of how to change the atmosphere of metal as a way to imagine a less oppressive and dehumanising way of being in relationship to oppressive or fixed ideology. Things are complex; sometimes things are extremely straightforward, and they are complex too.

** How have the events of this year affected your thinking on notions of the ‘real’ (say, with everything going digital) or our relationship with the ‘natural’ world?

ES: I’ve been questioning the idea of ‘real’ and a purist search for truth and authenticity for a while now, which has been especially important since receiving a warped understanding of what is deemed authentic or ‘natural’ through contemporary dance training; that perfection looks a certain way. It’s also important to say this is from my perspective of a white person experiencing a western education system informed by racist histories.

This conversation on ‘the natural’ also makes me think of a post I recently came across from Shon Faye: “Appeals to “nature” in objection to pleas for medical and bodily autonomy are inherently anti feminist and cis feminists who exempt trans healthcare from that have just uncritically accepted supremacist thinking about being a cisgender person.” There is a privilege in embodying what is deemed societally ‘natural’ which is why it’s important in this culture to unravel and question what is meant when the word is used. I think it can be extremely harmful.

** The intimacy of queer spaces is something that plays into your work; has the pandemic led to any reflections on the importance of physical togetherness in queer culture, and the future of queer spaces after all the difficulties of this year?

ES: What’s coming up for me with this question is the importance of queer family. The government hasn’t been supportive of non-normative relationship structures over the pandemic (which is obviously no surprise), and a queer family can literally be a saviour for many LGBTQI+ people living or recovering from abuse, abandonment or trauma. I believe club spaces can hold a kind of matrix where queer expression and love can be flowing and healing. Like a paradigm that understands time in a different way. I think other spaces can hold this feeling of consensual progressive togetherness too. In my experience being in a studio for creative movement research that is cultivating trust and a mutual sense of respect can hold this. I believe this can exist somehow still, we have always found ways.

** You mention horror in relation to Rubby Sucky Forge. I believe you’ll also be working with horror soundtracks for an upcoming performance of yours, Dykegeist, at the ICA next year. Can you tell us about your interest in horror?

ES: I became interested in horror more specifically around a time two years ago when I started feeling uncomfortable about a particular queer aesthetic that was growing and solidifying itself pretty quickly in the zeitgeist of the performance world. I’d probably describe this aesthetic using words like softness, fluidity, slippy. This isn’t a judgement on artists working with these forms; I’ve also been part of that movement. But when I took an optical view, my discomfort was around how the politics of queerness and its very ontology of resisting or not being able to become representational, was manifesting as something that was becoming recognisable. I became interested in the dichotomy of these places: being part of an artistic and political context from my understanding in the UK, and working with politics that want to somehow transgress a zeitgeist. Probably impossible. Horror became a way to speak to this kind of unmanageable cooptation of expression. I became interested in the body of a spider and how spiny, pointy, incredible and terrifying they can be. This imagery became a way to complicate essentialist narratives that can be given to the lesbian body. A haunting of a zeitgeist. Dykegeist will premiere at the ICA next year and the sound will be by Mica Levi which I’m fucking excited about.

** With the loss of club spaces there’s been talk of a ‘new normal’ online or socially distanced alternatives long into the future. A part of me thinks though that the missing intimacy between bodies means these will only ever work as temporary solutions. You work a bit with touch and intimacy in your work, what are your thoughts on intimacy in the pandemic?

ES: I still have hope these are temporary solutions. I’m trying to practice being more present, and in the present, as a way of dealing with the anxieties of unknown futures. This is definitely a conscious shift that’s happened over the last year and also looms in my work, as everything seems to. I’m trying to be okay with sadness, and what it would be like to be without the anxious need to be functioning again in line with a capitalist temporality, which to step aside from is also a privilege. I’m hoping the pandemic is offering a time of reflection and change within organisations or institutions and their relationships with artists. A real time to reconsider how research is funded and to what ends, with a greater and more holistic idea of care.

I do work with touch and intimacy and it’s very important to me as a way of connecting with a queer community around me, navigating queer intimacy and consent. This has been most prominent in my collaborative work and relationship with Florence Peake, through which we have been navigating a romantic separation during lockdown. This, I guess, has framed my thinking on intimacy in the pandemic. A transformative loss. I spent a long while dancing in my bedroom with a sense of moving with and for ‘the ghosts,’ as a kind of psychic transmitter and mode of connection to a queer community, and being present with sadness.**

Eve Stainton’s Rubby Sucky Forge, with Gaby Agis and Joseph Funnell, and costume by Sophie Donaldson, premieres live at The Place, London, on October 15, 2020.