The definition of a liquid, according to Wikipedia, is “a nearly incompressible fluid that conforms to the shape of its container but retains a constant volume”—to be liquid is to be responsive and adaptable. Observing the evolution of June Lam’s practice over the course of the global pandemic, I am reminded of these fluid qualities. The London-based Australian artist of Vietnamese and Chinese ancestry predominantly works in sculpture and live art. His sensitive practice has continuously explored questions of the boundaries of bodies, interdependence and intimacy through the mediums of performance and assemblage sculpture. Yet, the restrictions of lockdown forced Lam’s thoughtful methodology to shift into a medium he had not before used, as he began making 2D collage. This new way of working has culminated in a poignant series, titled Squeeze, to be exhibited at Ashley Berlin in early 2021.

In many ways, collage was already present in Lam’s practice, albeit in a different form. Particularly in his sculpture work, assemblages and arrangements of objects brought together incongruous objects such as century eggs and nail polish, Tiger Balm and concrete, acupuncture needles and glass wax, dish sponges and sweat. Interweaving Western allopathic medicinal objects with traditional Chinese medicine, and domestic with industrial materials, these quietly impactful works speak to woundedness, interdependence, porosity, connections to ancestry and attempts to heal the body. These themes have continued since Lam began arranging works on paper. Under the claustrophobic conditions of London’s lockdown, he has created a series of collages which capture the intense bodily anxieties created by this pandemic, in which desire and discomfort sit alongside each other. Squeeze extends beyond concerns around the spread of Covid-19, into the wider questions of Lam’s practice, particularly those surrounding bodies and touch. With images brimming with bodies and fluids, Lam’s playful and provocative compositions invite us as viewers to consider the politics of both our own liquids, and our own liquidity.

It is certainly a strange time for bodily fluids. One legacy of a staunchly heteronormative culture may be that self-describing as queer becomes a fraught, or even dangerous space in which you may be assigned a ‘queer body’. Setting aside the complexities and problematics of queer visibility, to move through space with a body that is read as queer is challenging in a world where queer bodies are inherently fluid and inherently contaminating. This is true, insofar as all bodies are fluid, contaminating: but these are not attributes exclusive to queer folks, and the idea that leakage is somehow shameful, is bound up in an archaic and violent notion of bodies as arriving clean and sealed, only to be dirtied by nefariousness. But for the non-queer, non-crip, or non-OCD people out there (and I’ve heard that they exist), Covid-19 must be something of a reckoning with their own seepages. Never did anyone predict that there would be so much public discussion of microparticles of saliva; of the dispersal range of a sneeze; of how much of yourself you spit out when you sing. Never did anyone realise quite how much we contaminate each other through handling the same plastic packaging that wraps three aubergines together. We are smearing ourselves all over trolley handles, door handles, light switches. When we flush a toilet we disperse a mist of our fluids. Who knew? Certainly the non-queers, the non-crips and the non-OCD folks didn’t.

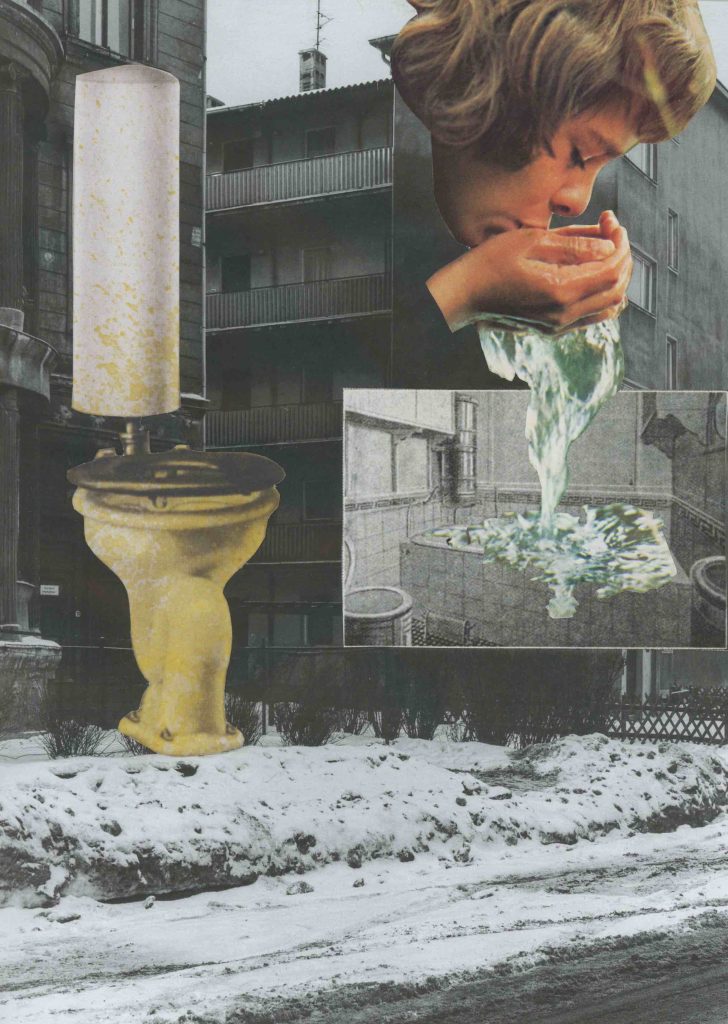

Throughout Lam’s collages, there are crisp lines and clear divisions between the source materials, but water appears frequently, as a tense mediator between fleshy bodies, and as a body itself. Water is pouring out from cupped hands into an overflowing bath, while next to it, a yellowing and splattered toilet hovers over snowy ground. In another image, a linear cartoon body produces a gush of viscous fluid from their chest, and a smaller trail from their mouth. Disembodied legs hover below upside down bodies of water; an enormous pendulous drop of water looms heavily over a person being baptised; a baby held by rubber-gloved hands floats above a beach at night.

Astrida Neimanis writes, “as bodies of water, we leak and seethe, our borders always vulnerable to rupture and renegotiation”. The liquids that emerge throughout Lam’s Squeeze series are fraught with these tensions. Water cleans, and infects. It threatens bodies and it connects them. It is always contained by the clean lines of the spliced image, but it always threatens to erupt, to overspill. Liquid is everywhere, in the background, the foreground, and it is beautiful and strangely unpleasant, an ambivalence thrown into sharp relief by the current pandemic discussion around just how much your liquids are lingering everywhere in the air and the surfaces you touch.

As someone who ticks all three boxes of queer, disabled, and having OCD, the Covid-19 pandemic has not been a reckoning, but it has been an undoing of sorts. I have spent many years shifting my compulsions from dominating my life to being well-managed. I recently came to the realisation that my agoraphobia and obsessive compulsive cleaning tendencies both stem from the same root, and that root is a form of queer shame. For the longest time, I could not acknowledge to anyone else that I had a body that leaks, for I had internalised the idea that a heteronormative ideal was poreless and impermeable, and as I was in denial of my own queerness, I therefore had to be impermeable. Thus, shame surrounding queerness and the inevitable leakage of my body became inextricably linked. Cleaning my living space has always been inherently bound up with trying to hide the horrific fact that I contaminate my environment, more so than any horror of my environment contaminating me. Occasionally that’s been the concern, too—there was the time I had a psychotic break and thought my housemate was trying to put bleach in my food—but overwhelmingly, the idea that I am not made of hermetically-sealed, poreless plastic is somehow intolerable.

It’s kind of horrific to acknowledge the residual traces that you leave behind yourself: the smudgy fingerprints, the greasy stains. I have learned to accept that I will leave these residual traces behind, that everyone leaves these traces behind, and that’s okay. However, we are suddenly being told that it’s not.Wear gloves, disinfect every surface that anyone has touched, don’t touch your own face. Invisible wet filth everywhere. So, like I say, an undoing. Being on the highly vulnerable list, receiving daily text messages from the NHS telling me not to leave the house, and also to clean everything, was a demand to go back to 2010. The contamination of touch is suddenly deadly, and no, it’s not in your head Rebecca, the government is sending you reminders via SMS.

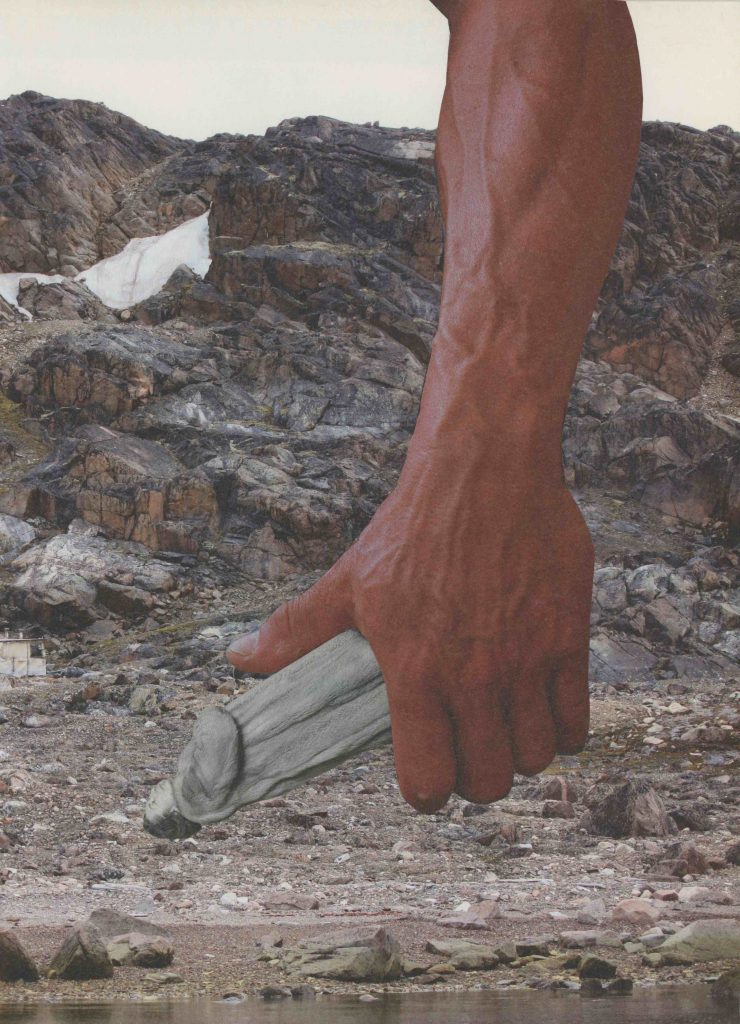

Hands are everywhere throughout Squeeze, which seems fitting given how fraught and rarified touching has become. Hands cuffed by microbial particles hover above a grassland. A hand strokes a hand which strokes another hand, like some kind of human centipede of forbidden contact. A veined and muscular arm holds what looks like a phallus, but reveals itself to be a tiny person in a fur coat. Mostly the hands are uncovered, but occasionally they are gloved—as with the creepy thick rubber gloves holding a baby—or covered in some way, such as the delicate fingers gently rising to stroke a painting of a penis, the fingers shielded by a tissue layer of fabric. These occasional moments, that hint to the tension of skin contact, make the unshielded hands look too naked, and as such, both vulnerable and threatening. I keep reading the term ‘skin hunger’ everywhere. It refers to the yearning for human contact as the result of being touch starved. Its other name is touch deprivation, but I like skin hunger. It acknowledges the visceral and frenzied state that a lack of touch can produce in a person. The hands in Lam’s work, though, are not just reaching out for human bodies: they extend to landscapes, to the mouths of fish, to flowers, to frogs. It is the yearning for an intimacy and connection, which for me has felt so lacking, now that everything feels like a threat again.

In the UK at least, lockdown rules privileged, and only acknowledged monogamous, cohabiting relationships and nuclear family structures, as social contact between households was restricted. What if you get your emotional and physical and sexual support from a different group of people than those you live with? How can your physical needs be met if you do not live with your sexual partner or partners? Beyond this, what if you do not ascribe to the idea that eroticism is phallocentric and genitally-oriented, and as such only takes place within specific scenarios? What if your erotic needs are met diffusely? As the legendary poet and activist Audre Lorde so famously wrote, “There is a difference between painting a back fence and writing a poem, but only one of quantity. And there is, for me, no difference between writing a good poem and moving into sunlight against the body of a woman I love.”

When I look at Lam’s collages, and its intimacy with other-than-humans—whether animal, plant, mineral, or plastic object—I think of sexecology, and queer animism. I think of the diffuse erotics of surface contact, and I feel a yearning to extend beyond my skin, the boundary which has been described (throughout a Western history of subjectivity), and is now being rigidly enforced (by government measures), as my bodily limit.

Considering the possibilities of true intimacy with other-than-human bodies, Mel Y Chen writes in Animacies, “many contemporary discourses continue to disavow, if not simply ignore, the possibility of significant horizontal relations between humans, other animals, and other objects.” , Throughout Squeeze, the landscape is not just a backdrop for human drama. The landscape is also a body to be caressed, to be stroked. Flowers are not servile metaphors for human anatomy, flowers are themselves deeply erotic: after all, to smell a flower is to stick your nose into a plant’s sex organs—orifice to orifice. There are recurring images of Kinbaku, an art form of rope bondage, spliced into Squeeze. But Kinbaku images are placed next to knotted pool noodles, and a snake wrapped around a gecko. Sexual charge is not partitioned, or limited to specific moments: there is eroticism everywhere. Not all of this is joyous, of course. The carp being held by human hands—its lips prized open, fingers entering its mouth—is one of many instances where contact is unwelcome. The gecko being held in an embrace by a snake is also being eaten. But this hovering borderline between threat and desire permeates the images in the same way that it is permeating my sex dreams. I want to gush outwards and I want to bathe in the liquids of everyone I encounter, at the same time as remaining tightly walled and shielded from them.

A part of recovering from OCD has been learning to embrace my fluid self. To acknowledge our existences as liquid and viscous is not to say there are no boundaries between selves, or that subjectivity itself is a mirage as we all inhabit a soup of collective consciousness. But contrary to the structures of a capitalist economy and the very notion of capital itself, we are also not entirely self-enclosed bodies, who can withdraw from and participate in the world at our discretion. Interdependence and interconnectivity are facts of life, facts which have to be suppressed in order for neoliberal capitalism to be justified. I used the term queer bodies earlier, as though the bodies of those who describe themselves as queer are somehow essentially distinct, rather than simply bodies who have been othered, and then wrongly classified as more liquid. But if a queer body is one which cannot conform, then regardless of your gender identity or orientation, your body is queer. No body can live up to the normative, humanist ideals imposed by Western capitalist patriarchy since the Enlightenment. You are not poreless, you are not bacteria free. You are oozing liquids all the time. I keep having nightmares about seeing large groups of my friends. I keep waking up in a sticky sweat after dreaming that I have hugged someone. Being on the highly vulnerable list has been terrifying. It’s a feeling like walking around with my skin peeled off, but constant physical distance is also making me sad. And hungry. And horny. The uncertainty, yearning and desire surrounding fleshly contact runs throughout these images. I want to reach across the screen and caress them, to give them a big squeeze.**

June Lam is London-based Australian artist of Chinese and Vietnamese ancestry, working across live art, visual art, acting, & dance. Rebecca Jagoe is a queer crip artist based in Wales.