Reading Mark Fisher’s K-punk, where many ideas of this essay originate, takes on somewhat of a double meaning in late 2020. On the one hand, it traces the object of ideology as it has weaved its silky way through pop culture, technology, social media and late capitalism since around the late 1970s through the 2010s. A common thread of observation by Fisher is that the self, augmented and understood through mass media, has emerged as the site of social and political action. Yet Fisher’s writing also strikes a melancholy note on the life of the writer himself, who so clearly observed and described a grim horizon that he could not see past. To this end, the essay is dedicated to his memory and to his work.

The ritual of being politically outspoken through mass cultural platforms is now unquestioned, if not downright expected, but this is a relatively new phenomenon. In the aughts, it was still a major breach of protocol to be politically vocal in public settings. Think for a moment, about Michael Moore protesting the Iraq War at the 2003 Academy Awards, or Kanye West in 2005 famously and, controversially at the time, saying in front of an embarrassed Mike Myers that “George Bush doesn’t care about black people.” Then, of course, came the financial collapse of 2008.

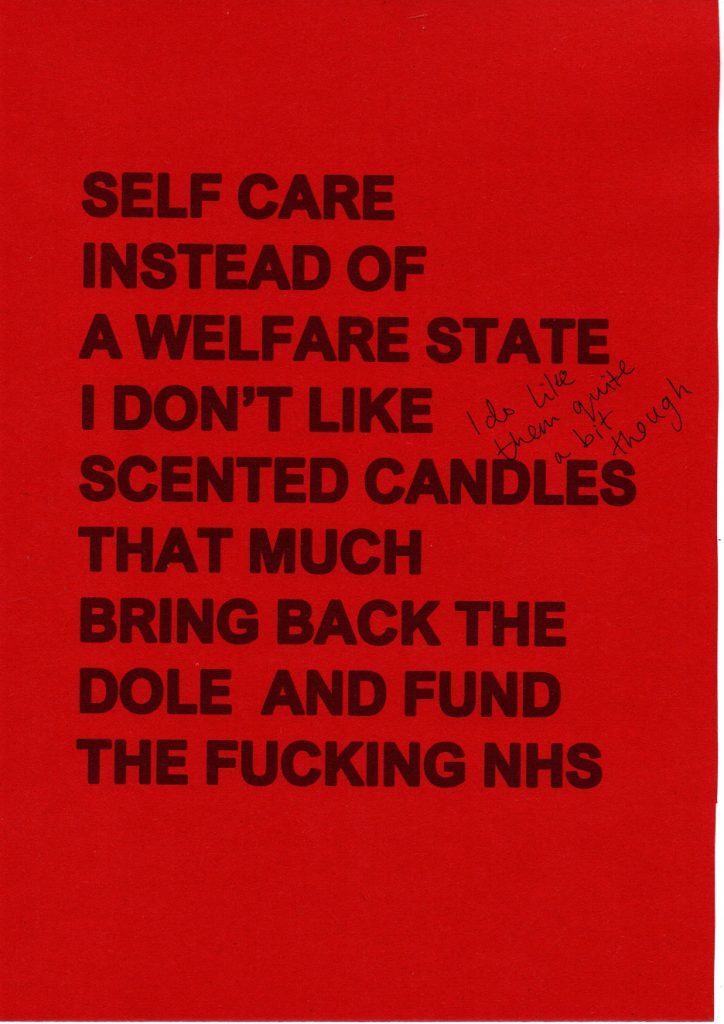

In its post-2008 economic recovery, the western world was haunted, as Fisher observed, by the ceaseless march forward of ‘capitalist realism’, or the notion that there was no better system than the flawed but better-than-nothing hegemonic global capitalist model. Into this climate came—perhaps around 2015/2016, or so—a greater awareness that things were unwell, but not unsalvageable. To deal with the stresses of an ever-growing cabal of authoritarian and neo-identitarian politics, on top of regular crises and breakdowns, a widespread movement of largely liberal, culturally-engaged, white, educated individuals began adopting the practice of ‘self-care’, propagated through the hardcore practice of Instagram posts, Snapchat and the newly-launched Instagram Stories function.

Speaking on ‘Radical Self Care’ in 2018, former Communist Party USA leader and longtime abolitionist Angela Davis, addressed the importance of the concept, while she was imprisoned in the 1970s to ensure the sustainability of both her own struggle and the resilience of collective radical action. “Personally, I started practicing yoga and meditation when I was in jail,” Davis said. “But it was more of an individual practice; later I had to recognise the importance of emphasizing the collective character, of that work, on the self.” Like Davis, self-care was promoted first in the mid-20th century by gay, Black and brown radicals, who needed space to uplift themselves within a system and society deadset on pinning them down, before being re-appropriated as a mass cultural lifestyle trend in the 2010s.

The re-emergence of self-care was powered by social media and the widespread acceptance that everyone deserved to treat themselves and heal from the drumbeat of regularly occurring crises. In a March 2016 story entitled ‘The Power of Rituals’, the trend was on the pages of online wellness platform Goop, where copywriters somewhat unintelligibly extolled the virtues of self-care, writing how “Cleopatra took baths of milk and honey, Helen Gurley Brown got ready for a party by submerging her face in ice water, Mary Queen of Scots soaked in red wine, Aphrodite in seaweed, Marie Antoinette in herbs.” A new buzzword was born and it widely proliferated.

The emergence of this self-care movement was well documented and also quickly criticized. Take, for instance, Jordan Kisner’s observations of the practice as of March 2017 in her New Yorker article:

Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that beneath the face masks and yoga asanas, many of the #selfcare posts sound strangely Trump-like. “Completely unconcerned with what’s not mine” is a common caption. So is “But first, YOU,” and the counterfactual “I can’t give you a cup to drink from if mine is empty.” I recently spotted another hashtag right next to #selfcare: #lookoutfornumberone. The image was an illustration of a pale, thin girl with a tangle of wildflowers growing from the crown of her head, reaching up with a watering can in one hand to water her own flowers.

Even in Kisner’s observations, self-care was already an expression of something much more sinister as part of the construction of the contemporary self mirroring the hyperindividualism of emerging right wing politics. But, taking this one step further, the self-care movement also offers an important glimpse into a similar impulse that had been defining the highly networked economy and society linked together via social media networks. By 2017, following the revelations of Cambridge Analytica, if social media wasn’t the ‘great liberator’ that powered the Occupy or so-called Arab Spring protests, then, at the very least, Instagram, Facebook, Twitter and others were a kind of personal refuge. They offered a personal ‘beach’ where everyone may safely wash up and rest their weary psyche, not only to rest and recover, but also share news, updates and advocate for political causes all from the comfort of one’s home. Self-care, merging with forms of ‘woke’ performative activism–the concept of woke, like self-care, also being another appropriation from Black American vernacular–were the new normal as expressions of both self and the collective.

Yet, the move towards privatized spheres of safety was not just a leisure function or extra-economic endeavor. Instead, it was promoted, enforced and surveilled by powerful algorithms, and social media became fertile ground for a merging of one’s deepest psychic drives with the new economic mode of production. According to Karl Marx, in his 1859 manuscript A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, he asserts, “The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.” How might Marx’s notion of a social existence apply with the platform of social media, particularly expressed via the phenomena of self-care or performative activism? Going further, how does the digitized social existence of the 21st century affect contemporary consciousness, while working hand-in-hand to drive economic activity?

As the neoliberalism of the 1980s put capitalism into hyperdrive, all humans were supposedly ‘freed’ to be independent economic actors absent the great sectoral and class divisions of the 19th and early-to-mid-20th centuries. Individuals were now free to buy company stock, reskill, become part of an aspirational middle class, and—especially in the US and UK—turn their real estate into high-value equity. Needless to say, wage growth stagnated as debt and individual risk skyrocketed.

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, society faced the great reckoning of this long drive of flexible accumulation, as it was clear that government and private finance were in league to generate as much surplus value as possible on the backs of individuals risking everything on increasingly precarious economic activity. The floodgates of cheap credit and low interest rates had been opened to retain confidence in the ‘supply side’ consumer economy even though wage growth was stagnant. Once the mortgages had become toxic, and the real estate bubble burst, people’s lives were smashed in ways that have reverberated to this very day, particularly for the generations under 40 years of age who are also the most plugged-in to online life. A corollary effect of this structural economic breakdown was skyrocketing anxiety and depression, as the hard hangover hit that economic activity is a private affair that concerned primarily individual responsibility.

In his 2012 essay, ‘The Privatisation of Stress’, Mark Fisher observed that depression and the condition of capitalist realism were not only interlinked, but causal. The flexible economic model offered no deeper level of comfort or stability, and rather required constant adaptation and vigilance to monitor change and flux. Writing in 2012, Fisher observed:

There is clearly a relationship between the seeming `realism’ of the depressive, with its radically lowered expectations, and capitalist realism. This depression was not experienced collectively: on the contrary, it precisely took the form of the decomposition of collectivity in new modes of atomisation. Denied the stable forms of employment that they had been trained to expect, deprived of the solidarity formerly provided by trade unions, workers found themselves forced into competition with one another on an ideological terrain in which such competition was naturalised.

In a world devoid of powerful trade unions, absent of readily available jobs and any class and cultural solidarities, humans had been ‘atomized’ and forced onto the market against one another, as competition. Society was now in an economic Hunger Games accelerated via digital connectivity. It should be no surprise, then, that from this anxiety sprouted depression, uncertainty and turmoil, out of which came the origins of a renewed populist Right as the new lords of protection from this terrifying landscape.

Absent a framework of social or political solidarity, it was now up to the individual to remedy issues for which they were ultimately not responsible, adapting to an economic model defined by empty-handed flexibility for all, and increasingly concentrated wealth for the few. Add to this an unprecedented economic crisis, a re-energized authoritarian Right, and a spineless center left, the idea of self-care became that much more tantalizing, one of the few reactions left available amidst the dark, alien, and lonely world of capitalist realism.

Though perhaps the term ‘self-care’ is more frowned upon now in 2020, manifestations of the self as the core of the social and political constituency still permeate contemporary social and political interaction, perhaps best seen in the onslaught of daily posts about “What YOU can do about [said social or political issue].” This ‘think global, act solo’ attitude is clearly seen in the current moment in the United States, with the calls to demand justice for brutal police murders of Black and brown Americans, as well as the daily advocacy to ‘#Vote’. Less attention, of course, goes to the fact that the systems of American carceral justice are themselves unjust, and most recently the President of the United States refused to admit whether he will even accept the popular will of the people come November, or whether their votes will even be counted in the first place.

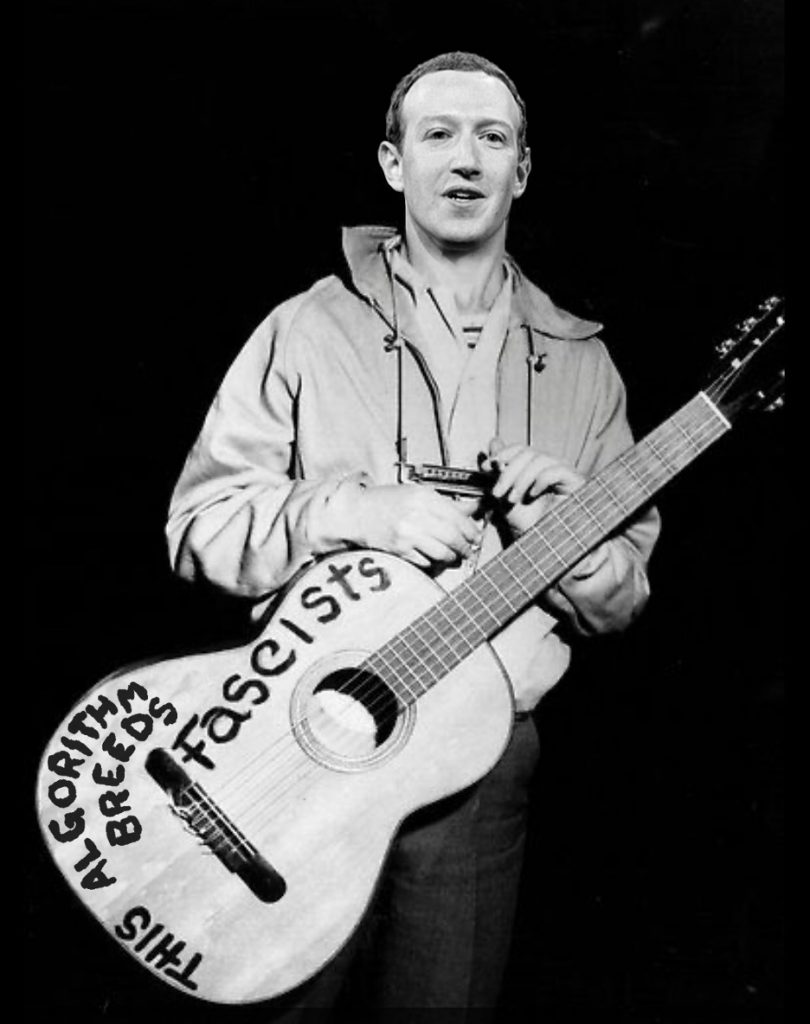

Despite these observations, it should be acknowledged that the resources and connections to community made available and accessible via social media–especially during the COVID-19 pandemic–should absolutely not be discounted. But social media is also not immaterial, somehow existing outside of an established economic or social system. Facebook’s commodification of outrage has brought us the kind of misinformation that has rejuvenated the Right, the rise of which (and failure of the political establishment to effectively combat) haunts our innermost selves every night. Stories, posts, Tweets, and even personal DMs have, meanwhile, provided for a false sense of security that praises individualized acts of ‘awareness raising’ as somehow sufficient to properly address and fix social problems. Think of all the black squares on #blackouttuesday posted the week after the George Floyd protests erupted that were thought to be a sufficient expression of collective outrage, but then were quickly criticized for drowning out those resources and voices that should have been given attention. Social media, simply put, was fully operating a central locus of social, economic and political forms of relation, exchange and production.

Back in 2000, the internet was still nascent, but it was around long enough for its effects to be observed by a growing pool of both sympathetic and critical theorists. One of whom was the Italian theorist and activist Tiziana Terranova, who presciently described the nature of labor operating within an open, decentralized information network such as the World Wide Web. She writes, in her 2000 essay, ‘Free Labor: Producing Culture for the Digital Economy’:

The cultural, technical, and creative work that supports the digital economy has been made possible by the development of capital beyond the early industrial and Fordist modes of production and therefore is particularly abundant in those areas where post-Fordism has been at work for a few decades. In the overdeveloped countries, the end of the factory has spelled out the obsolescence of the old working class, but it has also produced generations of workers who have been repeatedly addressed as active consumers of meaningful commodities. Free labor is the moment where this knowledgeable consumption of culture is translated into productive activities that are pleasurably embraced and at the same time often shamelessly exploited.

Terranova’s notion of ‘free labor’ is a reference to an emerging field of value production, seen throughout the user-generated nature of data and content on the internet. In its early form, even in 2000, the internet clearly required the input, enthusiasm and drudgery of millions of work hours from programmers, writers, graphic designers, marketing professionals, salespeople and users to sustain it as a collective space of social, cultural and economic interaction. The amount of engagement on the internet has only exponentially grown in the following two decades to a point at which most people are online nearly at all hours, generating nearly unquantifiable amounts of data that is processed, refined and monetized by powerful proprietary algorithms.

Adapting this framework of free labor onto social media use, it is evident how internet companies use data generated by user content and interactions to sell products, undergo market research and compile vast amounts of information that can then be sold to third parties. The business model of Facebook, Google, Twitter and Amazon are rooted, not from a kind of tech artisanal product development, but rather a monetization of user data and user activity to generate surplus value. Even writing in 2000, Terranova keenly observes about the user-generated profit model of AOL:

Commentators who would normally disagree, such as Howard Rheingold and Richard Hudson, concur on one thing: the best Web site, the best way to stay visible and thriving on the Web, is to turn your site into a space that is not only accessed, but somehow built by its users. Users keep a site alive through their labor, the cumulative hours of accessing the site (thus generating advertising), writing messages, participating in conversations, and sometimes making the jump to collaborators. Out of the fifteen thousand volunteers that keep AOL running, only a handful turned against it, while the others stayed on.

When the navigation of and interaction with the world is literally defined through one’s interactions with Google, Facebook, Instagram and so forth, the system of capitalist realism is inextricable from daily life when nearly all activity serves to help produce surplus value. On social media, ‘liking’ images of friends or colleagues at parties, at dinner or on vacation, helps inform the system of your own private desires. A frequently watched Story helps guide the system to prioritize which content you see first. The kinds of museums, artists, beauty products, or even cannabis brands that you follow builds out an externalized portrait of your internal mind as a late capitalist subject. You provide your own market research, and the algorithm rewards you handily with tailored content.

Terranova returned to the subject of the algorithm in a more recent essay in 2014, “Red Stack Attack: Algorithms, Capital and the Automation of the Commons”, where she further analyzed the algorithm as a site of surplus value production. Central to her essay was the suggestion of a ‘Red Stack’ that would create alternate online spaces of exchange and social relation not dictated by the surplus value drives of the capitalist market. Terranova writes:

However, it is not only a matter of using social networks to organize resistance and revolt, but also a question of constructing a social mode of self-Information which can collect and reorganize existing drives towards autonomous and singular becomings. Given that algorithms, as we have said, cannot be unlinked from wider social assemblages, their materialization within the red stack involves the hijacking of social network technologies away from a mode of consumption whereby social networks can act as a distributed platform for learning about the world, fostering and nurturing new competences and skills, fostering planetary connections, and developing new ideas and values.

For Terranova, the aim is to decouple the algorithm from consumption, and help undergird a radically new field of human relations. Algorithms themselves and the data they contain can be overturned, exploited, and reversed for the good of a “machinic infrastructure of the commons”, not unlike how film characters Neo and Trinity in The Matrix are able to peruse the wealth of data of the system and readily learn new forms of combat or skills to better aid their cause.

So then, given the transformative capacity for reversing the exploitative, proprietary algorithms that occupy daily life, how to go about the work undoing the toxic linkages binding the wellbeing of self to the digital ether? Terranova has one last observation in her 2000 essay ‘Free Labor’, relating the connections between the user-generated content of the early internet, and the then-popular medium of human-interest television (or ‘people shows’) of the ‘90s like Jerry Springer or America’s Funniest Home Videos:

From an abstract point of view there is no difference between the ways in which people shows rely on the inventiveness of their audiences and the Web site reliance on users’ input. People shows rely on the activity (even amidst the most shocking sleaze) of their audience and willing participants to a much larger extent than any other television programs. In a sense, they manage the impossible, creating monetary value out of the most reluctant members of the postmodern cultural economy: those who do not produce marketable style, who are not qualified enough to enter the fast world of the knowledge economy, are converted into monetary value through their capacity to perform their misery.

@ieatplutocrats Capitalismcore is hideous

♬ original sound – Pluto

Here is the productive and exploitative logic of the social media algorithm laid bare. It is a model that has supremely triumphed in taking the most common, anonymous, and withdrawn members of society and refining them into raw material for data collection and profit extraction. From this point, it is clear that the more outrage is expressed on social media, the more data is made available for third parties to use and exploit. The more that self-care and performative activism are thrown onto stories or permanent posts, the more the algorithm learns about which users are most receptive to such content and builds out yet another insular echo chamber among billions more.

Writing in 2012, Fisher concludes the ‘The Privatization of Stress’ by observing the emancipatory impact that both the 2011 London Riots and student protests a year earlier had on a younger generation squeezed by precarity and anxiety:

The recent upsurge in militancy in the UK, particularly amongst the young, suggests that the privatisation of stress is breaking down: in place of a medicated individual depression, we are now seeing explosions of public anger. Here, and in the largely untapped but massively widespread discontent with the managerialist regulation of work, lie some of the materials out of which a new leftist modernism can be built. Only this leftist modernism is capable of constructing a public sphere which can cure the numerous pathologies with which communicative capitalism afflicts us.

In an age lost within the deepest recesses of capitalist realism, the systems which hold this fragile world together must be undermined and overthrown. While popular social media platforms remain essential spaces to share resources for fundraising, activism, protest planning, news and learning, the smug self-branding of political affiliation as a political act itself simply needs to be tossed out the window. In a world defined by ever-increasing breakdowns, crises and externally-caused anxiety, the last thing anyone should be doing is receding into the isolated tidepools of the feed, freely toiling away their time and labor for the factory of privatized stress. It is time to build a new digital commons.**