Estefania Puerta tells me the word ‘lunar’ in Spanish means ‘birthmark’. Immediately I must reconsider her 2020 work of the same name, which I have been studying from pictures on my computer screen. Where I was looking for the moon, I’m now looking for a body—disoriented, thrown from my axis of feeling clever for knowing a word. Lunar is dressed like an altar and takes up space, tendrils of blonde hair protruding from a patch of dirt that frames a fleshy orifice like a tiny crater. Inside the hole is “nothing, like a belly button,” Puerta says over the telephone.

The Colombian-born artist moves fluently through drawing, painting, poetry, performance, sculpture, and installation, girded with a multilingual vocabulary of biology and ecology, mutation and beastliness; grime, water, milk, teeth, tongues, teats. She cites her first creative vocation as writing, and that early affair with words continues to buttress her practice. “Growing up in a bilingual household, I was always really fascinated by the double meanings in language,” Puerta said in a recent artist talk for Burlington City Arts. “I’ve always really connected to the simultaneity that language can provide.”

I first encountered Puerta’s work in 2017, when her installation ‘A Las Mujeres a Mi No Me Quieren y Es Porque Yo No Tengo Plata’ was part of the group show Interpose, curated by Susan Smereka for Vermont’s now-shuttered New City Galerie. Since then, she has continued to emerge as an artist, arts organizer, and teacher dividing her time between New York and Vermont, where she is a professor at Middlebury College. In the summer of 2019, Puerta curated the group exhibition Running through the world like an open razor, graciously including me on the roster.

More recently, her solo exhibition Sore Mouth Swore opened in February at Burlington City Arts and then promptly closed in response to the COVID-19 crisis. Puerta anticipates her next solo exhibition, Womb Wound, to open at New York’s Situations Gallery in the fall. With these exhibitions as bookends, and our revolutionary times as fodder, Puerta spoke about her work ahead.

**What are you working on and thinking about right now?

Estefania Puerta: I’m thinking a lot about organisms, to put it very broadly, and what does it mean to have a body that sustains itself? I am proposing these speculative organisms that have a function, when my past pieces have been more gestural. A science fiction around emotion and memory and how they can manifest in these self-sustained bodies—it’s an ongoing investigation of blurring lines between what a body and an environment is.

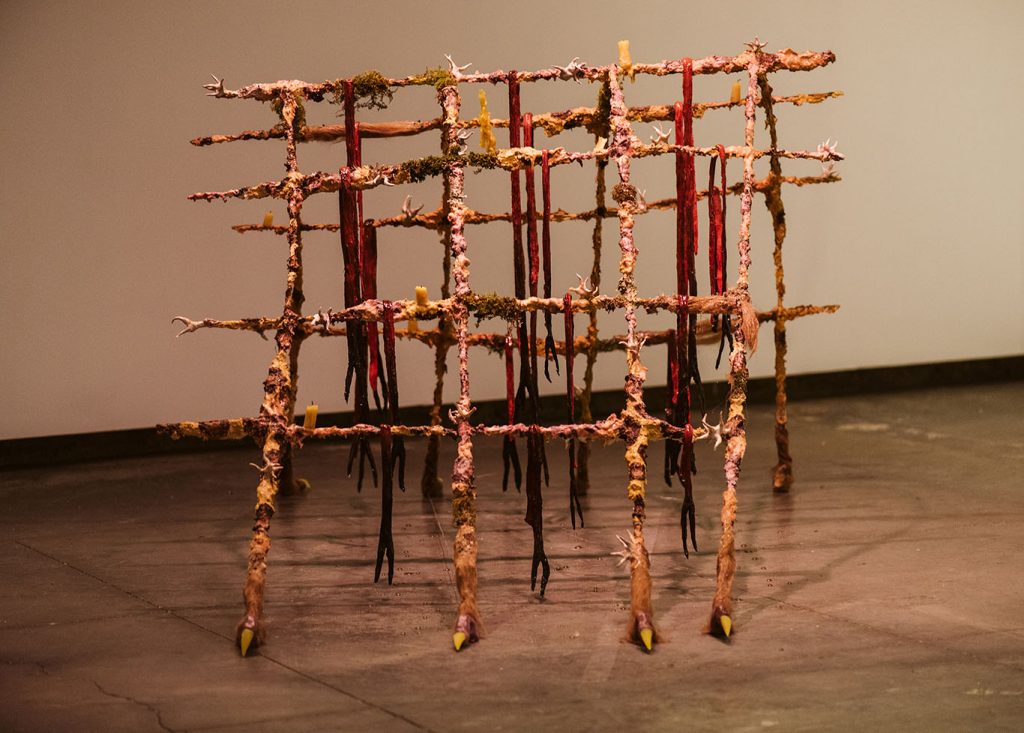

I call these works self-sustained bodies, but they don’t look like bodies. They maybe have an exoskeleton vibe to them. They have their own organized system for how to hold their own function, akin to organisms but also akin to gates, grids, furniture—structures that have been designed to hold a body or a set of elements. I am interested in the relationship between what is held and what holds when it comes to the relationship of the body and its organism.

I’m also thinking of what it means to hold memory, and what it means to sustain. I’m playing with the word sustain and sort of making fun of it, putting fruits in these glass orbs that will eventually mold. The transgressions of life that are mold and decay and fungus, these things are very much alive but are left to the world of refuse. That plays into the idea around what it means to be a transgressor in society, to be or have been a body that wasn’t accepted into this world yet thrives, yet fruits, yet grows in the shadows in beautiful multiplicities.

In some ways, I’m also being more direct around my own personal memories than I have been before. There are materials that I’m curious to explore and have embedded in the work—there’s one sculpture where I fill nylon sacks with my mami’s seasoning that is its own take on Adobo seasoning, which I grew up with. My mami would marinate all the meat with it, I have such a distinct memory around this. I feel a pressing need as my abuelas get older to document my family’s stories, all of the things that all of us eventually want to know in order to know our ancestors. I’m using these materials as an excuse to talk to my abuelas. I’m especially interested in the seasonings and smells and herbs that really call to them, as a way to encapsulate part of their memory. And yet, I can never know my ancestors, the disconnect is distorted, washed away by generations of shame and erasure. And so making these bodies that hold scent and known and unknown memories become my communication vessels to a history that is blurred and speculative in and of itself.

**You titled the exhibition where these works will debut Womb Wound. Can you talk a little about that title?

Estefania Puerta: I love this idea around an opening: you birth something out, at the same time it can hurt you. It’s a permeable space. When you have a cut in your body, it’s one cut in this heavily armored body that can react. Of course I’m interested in what healing looks like, versus keeping the wound open…What does pouring salt into it look like? What happens when all these openings are exposed to an exterior world they’ve always been armored against?

I like that Womb Wound is awkward to hold in your mouth—that’s a performative element of the title that I always get excited about.

**Does your work have a relationship to magic?

EP: I often want to give the sense of these things—my work—having a life before the one you see presented to you. For example that piece with the melted candles (‘All of Freud’s Beautiful Women’), I wanted that piece to have movement and evidence of life before…there were moments when there were candles a-blazing in my studio.

In Latin American culture, there’s a lot of commemoration and prayer, keeping flames going. I’ve used wax a lot in my work, and I’m getting more interested in candles. There is this material culture element—it’s not just wax to stand in for skin, there is this specific object that it’s made into that has this function of spirituality, hope, or mourning. I guess it’s not that I’m specifically interested in magic or the ritual, I’m interested in the materials that hold a lot of that kind of weight. Because a lot of work exists in this “weird” space of not being able to fully name it or that its science fiction presence is heavy, I have become more attached to these objects that exist in my cultural realm where my abuela could pause and look at a hideous cage-like drying rack monster and make a comment about prayer and commemoration. To offer bits of recognizable connection to the absurd.

Also,what is magic? In some ways, art is just a constant proposal of magic. Look, alchemy has happened, these things have become another thing.

**Can you talk more about the relationship between your work, language, and translation?

EP: Art is language and when you put language on top of language, it alway feels like you’re missing something. A lot of the work that I do, I righteously acknowledge that it comes from an emotional place. To intellectualize something emotional can be an inherently patriarchal ask—put some rhetoric on top of it, a winning argument where you set up your hypothesis to prove your point.

I’m very interested in speech exhaustion, this idea of exhausted tongues reaching a point of catatonia in the failure of expressing what feels like a truth that can be understood and needing to find a place to rest. Sore Mouth Swore felt very much like a world in which these bodies were tired, were sick of talking, sick of explaining, sick of migrating and shapeshifting and Womb Wound feels like a world where these bodies can rest, can regenerate, can find a healing place to be. And when I say bodies, I mean emotions, complicated histories of the self, and all the bodies we carry within us that feel impossible to explain. I also think of language rebellion in this. In acknowledging the colonizer in these languages, in these tongues, and how impossible it is to speak an ancestral truth through this colonized tongue and body. Again why for me, art is a separate space, a separate language that refuses to sit still and explain itself.

I’m thinking about the idea of word slippage, and delighted about the way that a word can so quickly hold itself and also come apart; that holding together and falling apart, and what’s holding what. I feel like the work that I tend to make is work that’s crawling out of itself a bit, it’s bursting at the seams. Uncontained, there’s no flatness to it. The whole question around holding and containment, and the way that those words can be so different from each other. What does it mean to be held, what does it mean to be contained—detained? The question around being trapped and being held can be so slippery sometimes. What does it look like to visualize both, together?

**How do you think that art workers and institutions can avoid racial tokenization and truly work towards an anti-racist art world?

EP: Tokenization can only happen in predominantly white spaces. It’s the first thing that has to go, by giving more curating and leadership positions to BIPOC communities. It’s so much about decentering whiteness in institutions. Right now, so many artists of color are being hit up with offers [from galleries and art organizations], instead of it actually being about fundamentally changing the infrastructure they’re working in. There is so much potential for harm when predominately white institutions bring in BIPOC artists and art professionals in the hopes for visual performative allyship, instead of fundamentally changing the infrastructure that has been steeped in white supremacist hetero-patriarchy. It feels so easy yet it begs repeating: Listen to BIPOC artists and art professionals. Abundantly pay BIPOC artists and art professionals. Immediately act on the guidance and feedback from BIPOC artists and art professionals. Stay humbled and in gratitude to the immense labor that it takes BIPOC artists and art professionals to exist in a predominantly white institution, and do everything in your power to change that reality. Even if it means giving up your power and job title.

In some ways the pandemic and anti-racist movement is the perfect storm, the perfect reckoning for the art world on both sides of it: a lot of small galleries are closing, have closed, and will close, which is always shitty. The blue chip galleries will be just fine. But I hope that we’ll enter a phase where artist-run projects can be more successful, if everything’s remote anyhow. Where BIPOC artist spaces will thrive and receive the support and visibility that allows for more autonomous spaces outside of predominantly white institutions. Space doesn’t matter anymore, that can be empowering. One can start decentralizing from New York and Los Angeles as cultural hubs, because you can be an artist anywhere and you don’t need a giant space to make art seen by a large audience, you may just need a computer and internet.

It feels really good to speak hope into the future like this, I have to admit it has felt so far away and impossible but to visualize BIPOC artist run spaces thriving and being autonomous while racists are outed and ousted from powerful art institutions. It feels good to say that aloud, to speak into existence and fight for.

I just feel like it’s a part of the whole dismantling of white supremacy. The art world is one of the biggest culprits of upholding and maintaining white supremacy. Museums are built on looting, and they continue to preserve the rigid gaze that artists are seen through and contextualized in. That part feels exciting for me—like, maybe I won’t have to forever be categorized in this Latinx immigrant artist box because it is undeniable that white supremacy exists in this way, which, believe it or not, was a fact that people in these positions of power would scoff at as of very recently and are still trying to mask and hide.

It’s such an overused quote—maybe because it’s perfect—but Jack Whitten said, “The political is in the work. I know, because I put it in there.” I’m always thinking about my family in the work I make, and there’s a lot of mourning attached to it. It’s my own way of processing sad and tragic things that have happened within my lineage. Those sentiments are present with me in the work. That’s still in there, it’s there, but I feel a little bit freer now than I used to. Right now, the simultaneous addressing of so many different things at once feels more authentic to what I’m actually experiencing, instead of what could be a slippery, nostalgic address to a slippery experience that has determined a lot in my life. I can say whatever I want because I am an immigrant and I have been a migrated body. I don’t need to answer that question anymore—I need to find radical comfort and sustenance in the wounds and new growths that have resulted from that experience.**