In Australia, protests in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement have centred around the long-standing campaign against Indigenous deaths in custody. There have been well over 400 deaths since 1991 (the year a damning Royal Commission report on the issue was delivered) and no convictions. Like elsewhere, the recent protests have provided a temporary lens through which recent acts of racist and colonial violence are given media attention: the blasting of a 46,000 year old Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura heritage site by Rio Tinto, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s denial of the historic existence of slavery in Australia, and new acts of police brutality. These are the kinds of all-too-common acts that Indigenous communities perform constant labour to bring to wider attention, but which are so often suppressed or ignored. Though attention also comes at a cost—an intensification of disingenuous ‘debate’, where Indigenous people are called upon to produce the same evidence and representations of trauma that they have been reproducing for decades. Sana Nakata tweeted recently: “I don’t understand why some people need [insist on] performance of Indigenous trauma in this country to be willing to rethink their understanding of Australia. How many massacres are enough/ how many deaths in custody?” The representation of Indigenous and Black lives remains caught in a heady flux between erasure and invisibility, sensationalism and hypervisibility.

The momentum of today’s global protests rely on what Nicholas Mirzoeff calls the copresence between visual and digital spaces, existing in “a set of interactive and intersensory relays”. Amidst this interplay are rapidly played out debates around both the expediency and ethics of image-making and sharing, focusing on issues such as appropriation, desensitization, and police identification. Images don’t simply flow from protests to an online space of representation, they have multidirectional effects. This came to particular light during the BLM social media blackout, where actions originally designed to give attention to the movement by asking people and businesses to suspend their usual posting activities, ended up creating a partial blackout of BLM activities themselves. It filled timelines with a grid of black square images, making it harder for people to access pertinent information about on-the-ground events. This fed existing suspicion of support seen as shallow virtue signalling and corporate whitewashing, a tension haunted by the larger spectre of widespread reliance on social media monopolies within an algorithmically-managed attention economy. This event also alludes to a larger debate around refusals of representation as a wider strategy (refusals to take up space, to repeat violent images, to resist forming narratives), that are skeptical of what representation can achieve and how it can be misused. But as Fred Moten has argued in In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition, denials might also inevitably reproduce, through reference and displacement, the thing they wish to refuse. As the social media black squares demonstrated through their shifting signification—from refusal, to concealment, to allegory for the flaws of online representation generally—refusal is part of a matrix of representational strategies complicated by our media environment.

Within this complex field, what role is there for artworks that represent protest movements, particularly those that are recent or even presently unfolding? Namely, contemporary artworks, which take representations of protest into a discursive art space and often rely on some proximity to protest movements, while being less implicated in their interactive relays. Such works seem to oscillate between realising historical effects; enacting gestures of memorial, remembrance and reflection, while also being tied to on-going political struggle and calls for action. While there has been much debate around the representational politics of contemporary art linked to Black protest and trauma, particularly focused on issues of appropriation and spectacle, my interest here is on the temporal relations of such representations and the question of unfinished business. For Indigenous Australians, the historical churn of continued injustices inevitably conditions issues of representation. The work of reflection, often performed through representation, is ever unsettled by new violence.

It is against this context that I want to relook at two artworks currently being shown as part of the 22nd Biennale of Sydney: NIRIN, which opened in March this year before swiftly closing due to COVID-19 restrictions. As the Biennale now reopens in the wake of a wave of Australian Black Lives Matter protests around the country, these two artworks, which are both tied to moments of Indigenous struggle against police violence, might be seen as particularly relevant to the current moment—although the urgency and visibility of this issue only waxes and wanes for those least affected by it. I worked on the Biennale before it opened, as a Curatorial Assistant to the Artistic Director, Brook Andrew, whose realisation of NIRIN (a Wiradjuri word meaning ‘edge’) is a web of interconnections and adjacencies. For me, the strength of the exhibition lies in de-centering a certain demand for representation (wherein the margin must make itself visible to the centre through endless re-performance), giving focus instead to relational affinities and kinships, often between colonised people, and around anti-racist and anti-colonial struggle.

Upon entering the National Art School—formerly the site of a colonial prison, the Darlinghurst Gaol—there is a leadlight window, placed on the ground, showing the figure of a young Indigenous man with a red target symbol on his chest, a form partly repeated by a yellow halo-like shape around his head. The work, ‘Brothers (The Prodigal Son)’, is part of an iterative series by Tony Albert, based on his witnessing of protestors at rallies against police violence that were sparked by an incident where two Indigenous teenage boys were shot and wounded by police in Sydney’s Kings Cross in 2012. At one of the protests, Albert noticed a group of young Indigenous men—friends of the boys who had been shot—had painted red targets on their chests. Honouring this gesture through partial re-enactment, Albert created his Brothers series by working with young Indigenous men living at Kirinari hostel, who he depicted through portraits where they beare different versions of the target motif. This latest version was created following Albert’s visits to the National Art School, where he’s quoted as saying he noticed a window in the Chapel building depicting the prodigal son—an instance of complicated beauty at a traumatic site of historic incarceration.

Placed on the ground outside, this leadlight work has not yet gained a more permanent placement, one that might imbed it within architecture and elevate it above our heads, solidifying its relationship to sacral and reverent forms. While ‘Brothers (The Prodigal Son)’ is the result of several stages of mediation from an original event (Albert’s witnessing of the protestors), by placing the work at street level and showing a figure at a human scale, the artist reinserts the image back into a social space. While the work depicts a defiant gaze that can be very directly engaged by viewers, its staging and medium is essentially precarious, so that it simultaneously embodies resilience and fragility, something present in the original gesture of painting a target as a defiant performance of one’s own vulnerability. If the religious overtones press the figure towards those of transcendent martyrdom, then other aspects embody vitality. Through the chains of relations the work references (victims, protestors, the men at Kirinari), we are brought to overlapping communities of young Indigenous men, ‘brothers’, who are still very much active, and vulnerable, and resistant in the struggle against police violence. For now, it seems, the object is not ready to be museified—to locate the violence it references only within the past. As implied by the title of another trilogy within the series, ‘Brothers (Our Past, Our Present, Our Future)’, these coeternal figures are bound not by a single act of divine sacrifice but across generations of connection. The work seems to anticipate its different meanings across times; maybe even a future when it is a memorial to colonial and racial violence, rather than still being firmly embedded within it.

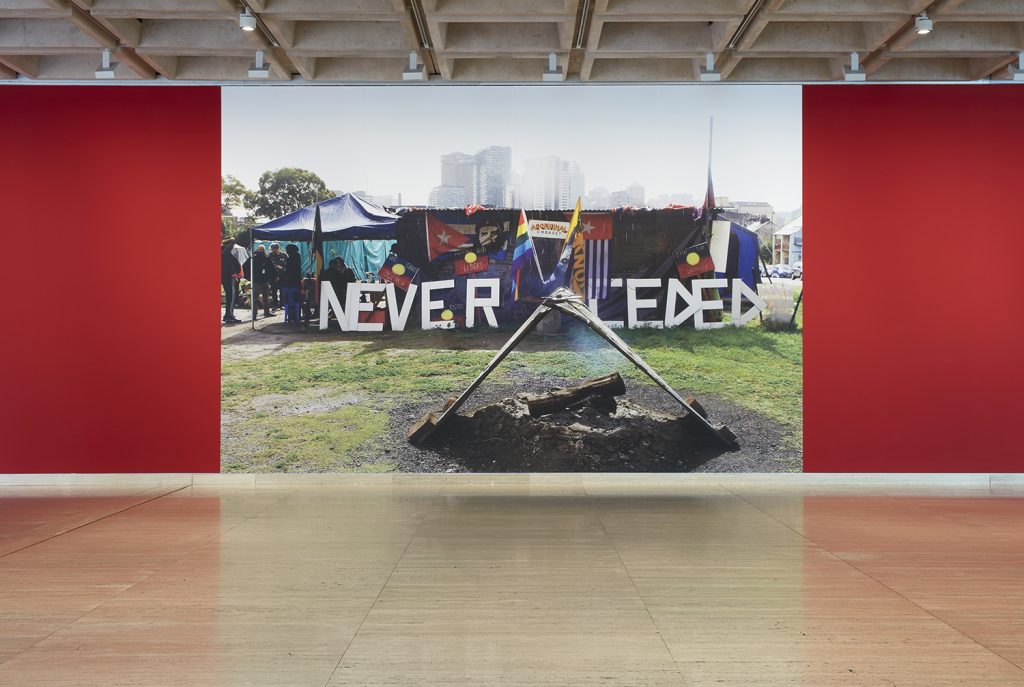

Within the grand Entrance Court of the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), are three photographs by Barbara McGrady scaled-up to cover the entire walls, each referencing a place and time of protest: a 2015 Black Lives Matter rally at Martin Place in Sydney, shown alongside an image of the Redfern Tent Embassy, a protest site set up by Wiradjuri elder Jenny Munro in response to gentrification, featuring a large ‘Never Ceded’ sign in front of a range of flags in solidarity with other global movements. On a wall around a corner from these two images, is a photograph of the family of TJ Hickey, shown collected around a podium where they were speaking at a rally in 2013, to protest his death at age 17 as the result of police pursuit. Together the images reflect localised moments of protest and their different formations of solidarity—between families, communities, and national and global movements. Most poignantly in the image of Hickey’s family, we witness both the individual and collective character of loss and grief, as we see his mother Gail Hickey supported by three relatives as she reads from a piece of paper, wearing a t-shirt of her son’s image, and standing in front of a sign reading: “Remember TJ Hickey”. While the family gather inwards, in a moment of care, their message points outwards, imploring the wider public to hear their story. In February this year—on the 16th anniversary of his death—family and supporters enacted their yearly march in his memory, renewing calls for a parliamentary inquiry. Slightly set apart from the other two images (and from other artworks in the Entrance Court), this placement gives space to a painful moment, while situating it in reference to proximate contexts of protest that are also fairly recent, tied to longstanding movements, and on-going in different ways.

Interestingly, both Albert and McGrady’s works play with registers of memorial in different ways. And yet, through referencing such recent injustices, for which there has been little to no closure, they exert strong links to on-going protest and struggle. They create spaces for remembrance with porous boundaries, opening out onto shifting, existing relations and contexts. Presented at a monumental scale in a place of historical veneration at the AGNSW, McGrady’s image of a family’s grief can be read as a memorial to the tragic loss it references. But like Albert’s image, both are also representations of acts of commemoration, drawn to the aesthetic and affective dimensions of such acts, the strength and vulnerability of friends and family members as they publicly implore others to remember the injustices committed against their kin. These works serve as a reminder that protests, particularly those over long periods, often involve practices of memorialisation, where remembrance is tied to calls for action. By honouring, documenting, and reflecting on the work of protest itself, we are also given a reflection on its social formations: the ‘brothers’ across a series of images, the family that physically surrounds and holds a mother as she speaks out. It is also notable that these works can be contextualised within series—Albert’s within his wider Brothers work, and McGrady’s through the display of a trilogy of large-scale photographs that reference protest. These are networks of images that situate individual figures within overlapping contexts.

As a photojournalist, McGrady’s images have circulated widely online and in news media. In a media landscape where there is both a dearth of Indigenous representation and virulent racial stereotyping, McGrady’s images project the multiplicity of Indigenous existence. Covering sports, celebrity, protest, art, culture, community, history, resistance, McGrady sees herself as both an observer and protagonist in the worlds she documents and participates in. In another major work for the Biennale, at Campbelltown Art Centre (CAC), her vast archive is shown as an immersive installation of projected images and words set to sound, a work described as a ‘Blackout’ within the white cube of the gallery. To be surrounded by these images, both through their large-scale presentation at the AGNSW and in the cinematically-rendered archive at CAC, carries the enormous affective weight of collected and collective experiences. It’s a counter-archive to what might be described as the daily ‘Whiteout’ of dominant Australian media to which McGrady has been a frequent intervenor. This, however, is not a politics only of Indigenous self-representation as the other to the white gaze, but an explosion of agentic images tied into complex on-going narratives and networks of connection, caught up in the on-going processes of colonialism, but never merely reducible to the trauma caused by white violence. These are stories with deep ties—as the title of the work suggests: ‘Ngiyaningy Maran Yaliwaunga Ngaara-li (Our Ancestors Are Always Watching)’. What if what is made is for them as much as for us?**

The 22nd Biennale of Sydney is on across venues, running June 1 to September 27, 2020.