“I want to maintain a certain affective pitch. I don’t know if that’s one of anxiety but I’m hoping that there’s abundance within that too,” says Vijay Masharani via Skype from his studio in Queens. He’s talking about his recent video, ‘Mourning in Advance for the future real death of my imaginary brother’. The piece appeared alongside Brooklyn-based Raza Kazmi’s work in their joint exhibition #38: Gas, Honey at New York’s Museum Gallery, running April 13 to May 11. This 27 minute piece employs culturally recognizable iconography to creating a familiar but alienating visual landscape. ‘Mourning’ explores the anticipation of state violence through the consolidation of sampled Guns N’ Roses songs, US Army insignias, arrest footage, and a gamut of YouTube videos, into a vernacular of contemporary media sources.

In Masharani’s videos, expressions of power come under scrutiny where they are consistently rendered invisible and unassailable. Authority is not recognized plainly but is felt as an index of the larger structures standing behind fraught gestures and images. It’s as if Masharani’s recent work puts forward a primer on how to read white supremacy’s encoding in the vastness of digital media. Within this decoding effort, there is space for recognition, poetry, and proposal, as well.

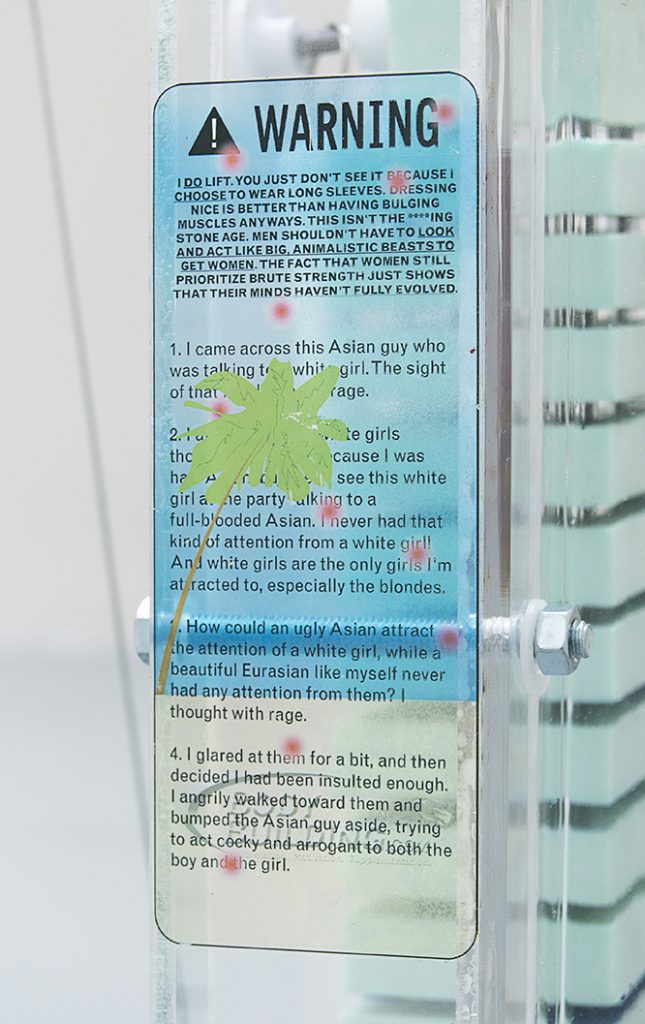

Masharani’s 2017 show It Might Be Warm But It’s Not Clean with Trisha Cheeney at Philadelphia’s High Tide examined masculinist fragility, drawing from a widely circulated shooter’s manifesto. Their collaborative piece, ‘FEELME’ reminds us of the violence that arises out of the confluence of fragility and power — the manifesto’s author, imagining himself as utterly disenfranchised, weaponized his self-hatred in a rampage in Isla Vista in 2014. ‘FEELME’ consisted an acetate, insulation foam and CNC-milled weight lifting machine, mounted with dogmatic texts and diagrams. Along its sides, a chart for bodily maintenance instructs users to “Inspect: Groin, Biceps; Amazon Cart; Gun Legislature, Affect Industry.” These regimens cohere in the form of a legible Bro: one who embodies toxic masculinity through his participation in fitness culture and entitlement to sex. ‘FEELME’ investigates disempowerment (in this case self-constructed), as this figure reenacts the conditions of his victimhood in endless, looping psychodramas.

In May 2018, a subscriber to Arab Andy’s YouTube channel donated $4.20 to play text-to-speech audio announcing a false bomb threat to a University of Washington classroom. Audio from the original live-stream — which shows the stunt, Andy’s navigation of UW campus during the subsequent manhunt, and his ultimate arrest — appears at the end of ‘Mourning’ Masharani describes his concern with the “aesthetics of passivity”, which can be measured, for example, in Andy’s performatively neutral vocal register as he is being arrested. Alongside this self-preserving mechanism, a sensorial lexicon connoting power emerges—one in which empowered subjects weaponized their own imagined fragility to inflict real harm. In ‘Mourning’, attention is drawn to how the most transient of signifiers (light, pitch, syntax, memory), are mobilized to convey the presence and authority of the state. Figures in Masharani’s work exist within this constellation in perpetual states of heightened vulnerability, ever-vigilant for these specters. In this conversation, the artist discusses disempowered subjectivity, the eugenics of the fitness industry, and false victimhood within displays of hyper-masculinity.

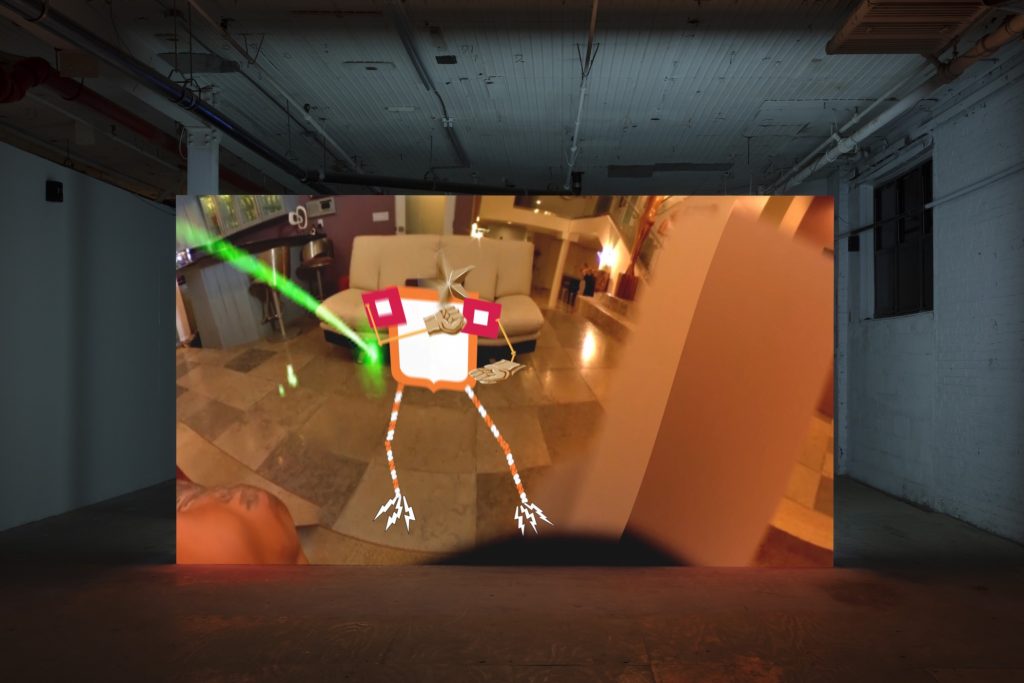

Vijay Masharani, ‘Mourning in advance for the future real death of my imaginary brother’ (2019). Excerpt

**I’m interested in how your use of recognizable cultural tropes flies in the face of what those tropes embody. For example, in the score for ‘Mourning’, you sample Guns N’ Roses’ ‘One In a Million’, which is so anti-black and xenophobic that you want to believe that it’s a self-reflexive parody of white fragility, but it’s not. It was totally produced at face value.

Vijay Masharani: The song is abhorrent—in terms of sampling it, it was really the whistle that did it for me. [Asking], “how do you allegorize whiteness,” is something that I’ve broached in the past. How is it encoded? I catch myself obsessively trying to locate whiteness, which is sometimes blatant, but oftentimes evasive and pernicious. So, framing white supremacy as a whistle to me felt potent—it’s tinnitus, it’s inside your ear. I would never sample the lyrics of the song, but I’ll take a riff and a whistle. A lot of the time, I’m trying to coax certain qualities out from something. In that case I wanted to coax the whistle out—that happens through the loop, the fade, the drums.

**You use the loop musically, but also to prolong bodily gestures that are unsustainable. I’m thinking about the video game character, Ness, who you show stuck on the edge of a platform wall about to fall forever. Or the chimpanzee in ‘You Can’t Turn Me Away’ that’s always about to drown but is forever in the moment just before.

VM: In general, I’m bad at action but I’m good with states. So this state of suspension, and this dilation of that state of being on the edge of something—that’s what I’m inclined to make the characters in this film do. And I think it’s conceptually important for them to be unable to act. That’s why a lot of the time they’re kind of prostrated—they’re being acted upon. Larger forces are flowing through them, and their agency is diminished on an individual scale. I recognize that this may read as pessimistic—to represent figures stuck in a disempowered state—but I don’t think that emphasizing a state of passivity forecloses the possibility that there is resistance happening elsewhere.

**I think that passivity is legible in the text referenced by ‘FEELME’, from your show with Trisha Cheeney. The narrator just wants to stay in this disempowered state forever, because he identifies too heavily with the conditions of his misery to confront them. This person needs to remain victimized in order to feel vindicated.

VM: The source text for that piece is the manifesto of the Isla Vista shooter. I was a freshman at UCSB when that happened. To me, he’s fragile and refuses to admit power. I was excited by the diagrams on the cable [weight training] machine in that piece, and to figure out what to do with those. I was thinking about how the sentiments in the manifesto were similar to those first expressed on the early alt-right spaces of bodybuilding and pick up artistry forums. Trisha and I were already making a gym machine, so we were thinking about fitness, and the eugenicist logic that’s espoused by the wellness and fitness industry. I selected passages where there was an invocation of racialized self-hatred. So diagrams became a way to bridge the diffuse white supremacy of the fitness industry with the concrete fascism of the shooter’s manifesto.

**In contrast to a polemical style, your more recent approach relies on poetics to obscure your subject. I see this in your departure from appropriated text and lecture, but also in your use of footage in ‘Mourning’ showing migraine simulations or people and animals having seizures. It’s a much less tactile way of thinking about the body than the way you employ fluids in earlier work.

VM: It relates to what I call the aesthetics of passivity. The seizure is maybe an instance of this, it’s a calamitous passivity. It’s an internal revolt as a response to an external stimulus, which is as immaterial as light or sound. It’s a condition unlike many others because the body acts so violently and expressively. If you think about an ailing body, you tend to associate it with a kind of attenuation, as opposed to a seizure, which takes the form of a hyper-concentrated moment of intensity.

**What do you see as the relationship between the “aesthetics of passivity” and the corruption of video as a medium, and how that extends to the politics of surveillance? What intentionally or unintentionally brings surveillance into your work?

VM: I talked about diagrams earlier; in ‘Mourning’ it takes the form of the crest of the US Army Signal Corps,which manages communications and information systems, including military intelligence. The crest features a fist grabbing lightning, representing how “the Corps has grasped the lightning from the heavens”. In other words, the crest invokes a transcendental authority. Surveillance footage invokes its own authority—especially if it’s shot with a wide angle lens, and from a particular vantage point. Surveillance emerges in my work as a consequence of the technologies I use and the fact that I am kind of obsessed with the grammar of authority.

**That index of authority you’re describing seems really present in the audio from Arab Andy’s arrest, or that incident in general. That audio, which you include in the last three minutes of ‘Mourning’, is just an end result of something that we don’t see—but its tropes are so encoded, you already know what’s going on.

VM: Right, partially because it’s a genre. My friend sent me Arab Andy after he had been arrested. I found him to be a tragic figure; he’s a performer for an audience of mostly teenage reactionaries who all applaud his broadcast slow death.

It’s also his life, so it’s tenuous to recuperate his experience into an aesthetic form. That’s where my specific transformations are highly consequential—it’s important for me to not show police violence, and to only take the audio. I feel freer to appropriate sound, maybe because of the established tradition of sampling. But also, audio literally bleeds—it’s this slippery and permeable format; that affords me a certain freedom.

**I’m struck by the tone of Andy’s voice—I don’t know whether to call it passive. There’s his repetitive use of the word ‘bro’, but as he’s being arrested, he’s so calm.

VM: I would just attribute his calmness to the fact that cops will use anything and everything as a pretext to kill. Andy’s syntax is peculiar—when you’re in those moments of heightened stress, I imagine that your most basic vocal tics come into focus. Calling a cop ‘bro’ while he’s arresting you is strange because it’s a futile attempt at camaraderie.

** ‘Mourning’ speaks to the paranoia of an ever-present threat, which is subsequently validated by the thing actually happening, thereby invalidating the category of paranoia itself. You can’t call it paranoia if there’s a good reason to be scared.

VM: The mental state of always-anticipating harm is something that comes up again and again in my work.

**You often present a totally absurd, intolerable reality as something that has to be a joke but completely isn’t. For instance, you show a few frames at the end of ‘Mourning’ from Joey Salads’ ‘Getting Water Boarded Challenge’, in which people consentually torture each other. The first response of this person who has just been waterboarded for entertainment is to say, ‘that was not nice!’ The unseriousness of that line seems to mirror Arab Andy’s use of ‘bro’. I don’t think you can call what Andy’s doing ‘masochism’, though.

VM: He chooses to substantially lean into the risk that comes with being of a certain ethnic makeup in public, which is itself interesting. I would call that a form of masochism but with different origins. What makes Arab Andy turn to masochism has more transgressive potential compared to what makes the white dude turn to masochism. Hence, the drama of watching Andy comes from that he has everything to lose—whereas in a quasi-homoerotic clout ritual, the masochism is contrived, banal, and…

**It’s sadistic.

VM: Yeah.

**It’s sadistic because the humor that they’re finding in it relies on others actually being waterboarded.

VM: It’s not even waterboarding. Technically there is a towel on your face and somebody is pouring water on you but there’s no real power dynamic. Within this rehearsal of torture, there’s this strange phenomenon of white men simultaneously caricaturing and sanitizing imperial violence through their own homoerotic desire.**

Vijay Masharani’s video ‘Mourning in Advance for the future real death of my imaginary brother’ was presented at the #38: Gas, Honey joint exhibition with Raza Kazmi at New York’s Museum Gallery, running April 13 to May 11, 2019.