Enter a familiar scene: a gallery opening in late summer. The crowd spills into the street; there’s a perennially emptying drink bucket, and of course, the artwork. An oil painting, mixed media wall work, and site-specific installation perched on the windowsill form a perimeter punctuated by several assembled sculptures: two placed on the floor, and one dangling delicately from the ceiling. What sets this particular night apart, marking the haecceity of an event that could otherwise be anywhere—Los Angeles, Berlin, London—is its bittersweet nature. It is both a celebration and an elegy; at once the opening of the group show Routine à la mode, running July 18 to August 18, and also the closing of the longtime home to the gallery hosting it: New York’s Kimberly-Klark.

The exhibition takes as its central premise the concept of exercise, or routine, as a pointless process that is nevertheless productive through its durational practice. According to the press release—which is, frankly, a pleasure, sparing the reader the usual pitfalls of overwrought description and context-less quotations from philosophers du jour—it’s a way of “going through the motions day in, day out,” without end. It’s curious then, how static the works in Routine à la mode initially seem. They lack kineticism and only gesture towards process. Camila Guerrero’s ‘More Brighter’, for example, tackles sport directly by including a neat line of billiards chalk among its assembled materials, while Dylan Vandenhoeck’s ‘Subway’, transposes the speed of the underground train into the visual field, warping perspective to give the eye the rush of the ride.

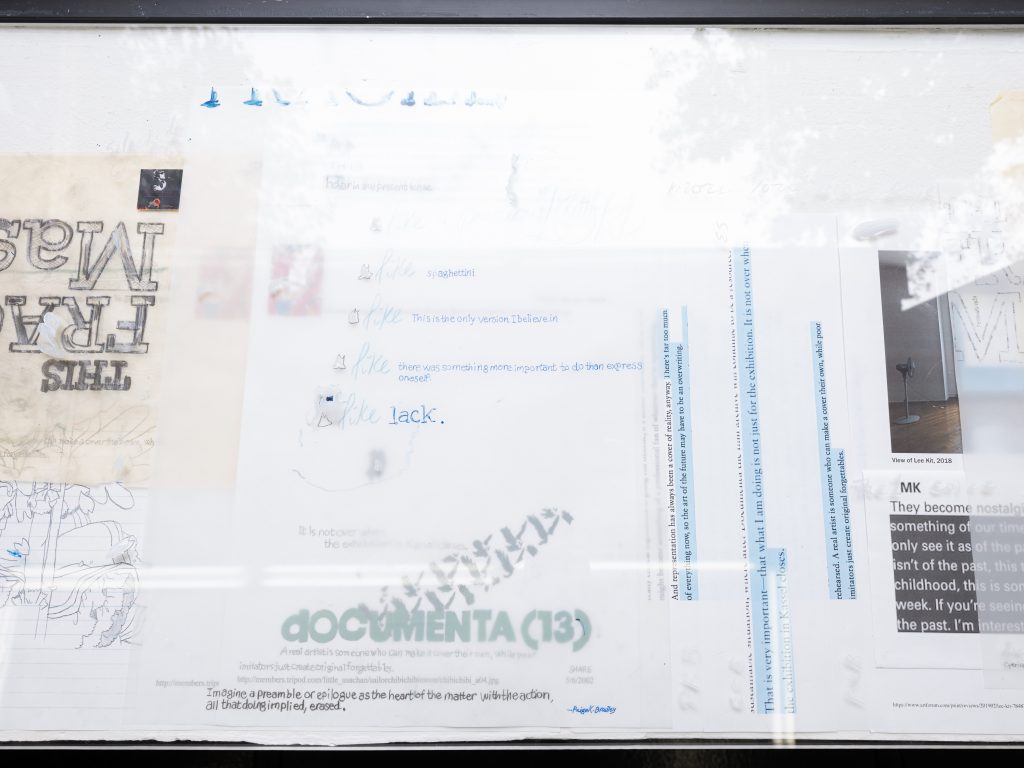

Paige K.B. enacts the theme most successfully with her 2019 site-specific collage ‘imagine this publication from exceedingly minor riffs Toward a Theory of giveth and taketh away w/breaks for Paige K. Bradley’s correspondence in a stream of promise’. It’s difficult to describe exactly what this piece is or does, with its 24 listed materials, but that might be exactly the point. Small drawings of birds sit next to hand-written notes, all layered on top of printed texts ranging from reviews in Artforum written by the artist, to an old interview with Mike Kelley. A moodboard of marginalia without a body to orbit, it’s a site of endless conspiratorial connection that inspires the ceaseless appetite of the paranoid mind, where logic runs amok, endlessly associating and attempting to discern the link between spaghettini and Gertrude Stein. Try as they might, however, the six works, one by each participating artist, only tenuously achieve true motion, and ultimately they rest—as objects placed within white walls tend to do—with a rarefied air that discourages action and cautions against movement, lest they be disturbed.

To leave it all here, as a review ending with a declaration of mixed success would be unsatisfying. It has barely scratched the surface and there is too much left to say. Such a method of criticism is too closed off in its tracing of standard curatorial practice—establishing an a priori principle within a delimited selection of artworks—to interrogate this idea of exercise. After all, as Foucault iterates in his essay on Velázquez’s ‘Las Meninas’ painting in The Order of Things, technique and language must match their object of study, so since this type of evaluation is driven towards a final purpose, how could it address the purposeless nature of routine? Maybe it’s the lingering effects of Paige K.B.’s work—it’s hard to shake suspicion once you’ve started seeing patterns everywhere—but it may be time to take up the conspiracist’s refrain and go deeper, looking for connections wherever they may come.

Where better to begin than the most obvious point, with the art of Nik Kosmas, who literally engages the practice of working out. First coming to prominence in 2006 as part of the interdisciplinary audiovisual duo AIDS-3D, his work engaged in the puerile post-internet-isms popular at the time. Like many of their contemporaries, Kosmas and collaborator Daniel Keller mashed up a fetish for new media and internet culture, an embrace of corporate aesthetics that too easily shifted between irony and earnestness, a surface level understanding of critical theory, and a nod towards classical sculpture and form. The outcomes of this process, such as the 2007 sculpture and animated gif ‘OMG Obelisk’, left little to grasp, and no firm ground on which to establish a practice, let alone build a life. “At some point,” Kosmas states in an interview with Spike Magazine, “I had the feeling that I couldn’t explain what I was doing, with conviction, to a stranger.” That’s when he turned to what he had previously considered ‘hobbies,’ and began to directly engage fitness and nutrition as his practice.

Kosmas’ art here collides with the Routine à la mode group exhibition. Try as one might, there’s never a concrete end with exercise. Even the most perfect body, or the strongest muscles, atrophy if left alone. Without upkeep, without routine it all comes crumbling down. Consider Kosmas’ contributions to the 9th Berlin Biennale in 2016: ‘Power Rack, ‘Rig’, and ‘Squat Rack’. Their simple names perform all necessary description, acting as indexes of what they claim to be, namely, brightly-colored versions of the steel, modular exercise equipment used by weightlifters. Just like their namesakes, they are intended to be used, and every Saturday during the biennial, Kosmas and other trainers held regular, guided workout sessions for the public. The key here is the insistence that the artist’s contributions are not a statement, installation, or performance but instead ‘simple structures’. Their being aligns with action, and they are exactly what they do: creating structure through durational practice, pulling together the physical and the social fields into a particular form, with all its attendant meaning—but only for as long as they last.

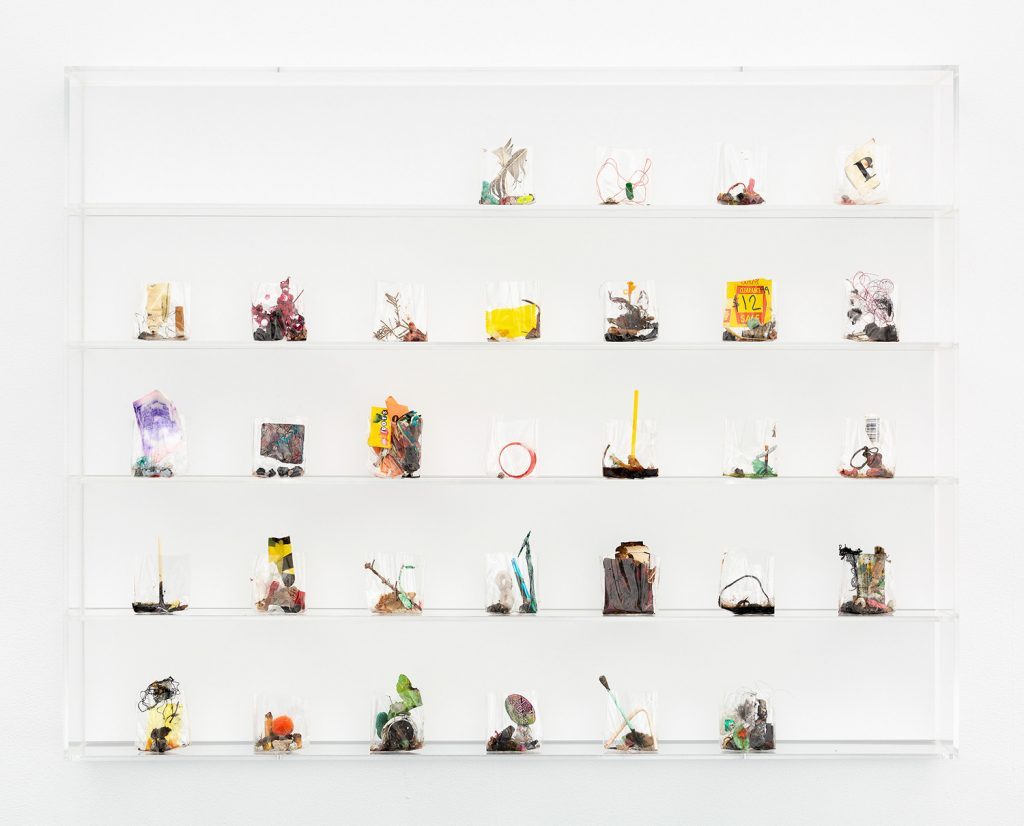

Biennials, however, are only temporary, and after three months these simple constructions, were dismantled, undoing the world they had formed around them. Looking for a longer timeframe leads to the work of Yuji Agematsu, who has taken daily walks through the New York for the past 40 years since moving to the city. The artist’s wanderings eventually developed into a more concretely productive practice, where he would gather miniscule bits of garbage found during the stroll and arrange them in daily collections. At first they were contained in Ziploc bags but later in what he terms zips, the cellophane packaging from the cigarettes he habitually smokes daily.

Though at first it may seem like these walks truly do have a point, since they result in discrete works, each sculpture only has meaning within the context of the whole. They are only exhibited within larger sets, organized by periods of time, and ultimately—as nearly all writing on Agematsu notes—they are distinguished by their process, the ritualistic walking that has continued, unceasing, for so long. This very routine ties Agematsu to the world in ways beyond art-making, structuring time through indeterminate scheduling and the smoking of cigarettes, bringing him into contact with society through its castoff detritus, and experiencing the political through the contentious process of urban development over the years. Through the encounter with his zips, the viewer collides with this very world, extending it beyond its material boundaries.

As different as they are, a common thread emerges between the work of Kosmas and Agematsu that remained unseen within the strict context of Kimberly-Klark’s Routine à la mode. The power of praxis is not how it is expressed in content but how it structures form through process in order to create a world, leading to new modes of meaning and action alike. Accordingly, the show’s theme should not be located in the works it brought together, but instead in the very conditions that made it all possible: Kimberly-Klark itself. Running a small project space like this is largely a thankless task, predicated on exactly the repetitive routines—studio visits, installs, openings—that motivate the group show. There’s never a precise goal, no real motivation for growth or scaling, only the hope for continued existence, and the holding of a ground for the friendships, scene and community that it brings about.

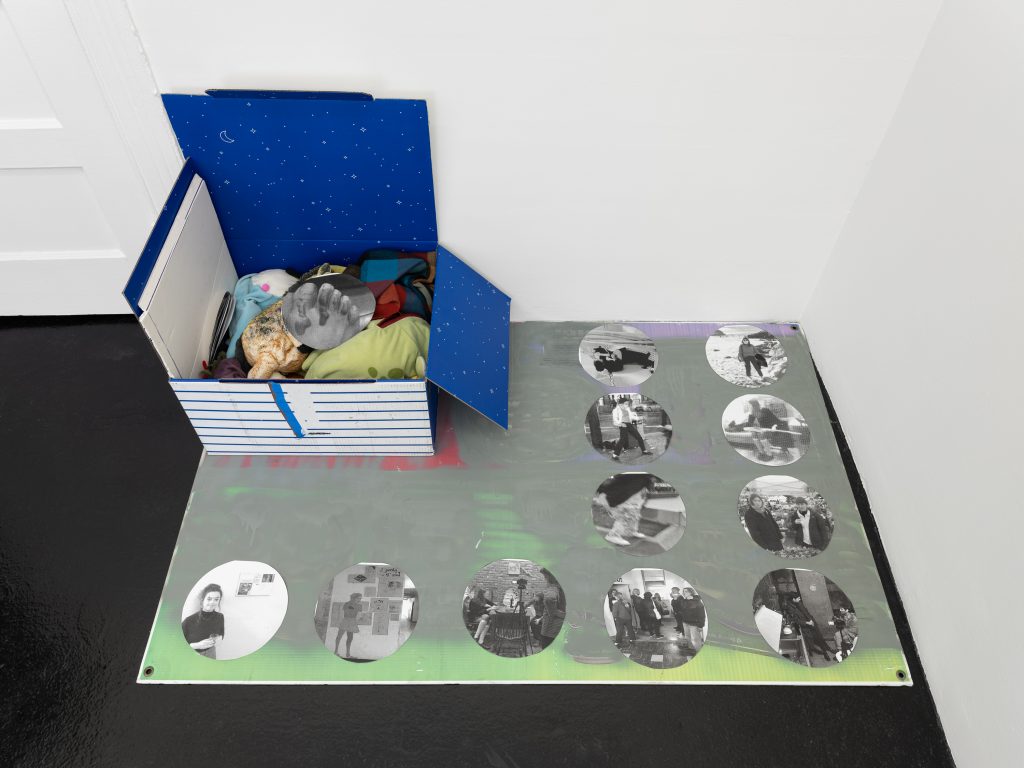

Returning to the night of the opening with this in mind, everything seems different. Caught amidst the crowd, Bradley Kronz’s mixed media wall piece ‘A Star Is Made + Wet Spot’ continuously gets bumped into, knocking ajar its framed drawing of a firefly, and commanding the Kimberly-Klark directors to ceaselessly rush over, straighten everything up, and implore visitors to have fun, but please be careful. Tucked away safely in a corner, Rafael Delacruz’s ‘record player with vinyl’ contribution interacts less directly with the people in the room but through its material. Instead of pressed wax, the records here are hand-cut photographs that reference past exhibitions and openings. In this remixing of events from other places and times, it situates the current show and puts it into play with the broader sphere of contemporary art, ultimately engaging the scene itself.

Firmly ensconced in the murky mesh of the social, these works become ‘quasi-objects’—a curious category coined by French theorist Michel Serres referring to that which is neither fully object nor subject, but somewhere in between; both acting and being acted upon, like a soccer ball that simultaneously structures the players on the field, even as it cannot but help being kicked around. By assembling these works, Routine à la mode becomes a quasi-object itself. It is at once something to be viewed and contemplated, while also acting as an alluring force bringing people together. It might not be directed towards a specific end, but as the press release aptly notes, at the very least it’s “a good reason to leave the house.”

Without becoming maudlin, it must be mentioned that there is now one less reason to leave the house. As Routine à la mode closed on August 18, so too did this chapter of Kimberly-Klark’s life. Endings rarely come at a good time, always too early or too late, but the show is a fitting finale to the gallery’s nearly five years of existence at 788 Woodward Avenue. Though the routine has come to an end, something of its structure lives on, through the influence and network spread far beyond the neighborhood of Ridgewood in Queens, lingering in those who came into contact—whether directors, visitors, artists, critics, viewers, or someone who stopped by only for the free beer. In the end, it’s just like the old adage that maybe the real art is the friends we made along the way.**

The Routine à la mode group exhibition was on at New York’s Kimberly-Klark, running July 18 – August 18, 2019.