To watch a ping pong match is to witness an intimate, intricate exchange between two people. The players are their own and each other’s choreographers, changing boundaries and possibilities, guiding the other’s body with their swings and twists. In Thuy-Han Nguyen-Chi’s What My Eyes Behold Is Simultaneous solo exhibition at Chicago’s SITE Galleries, the game of table tennis serves as imagery for these loops of influence between people on small and vast scales, across space and time.

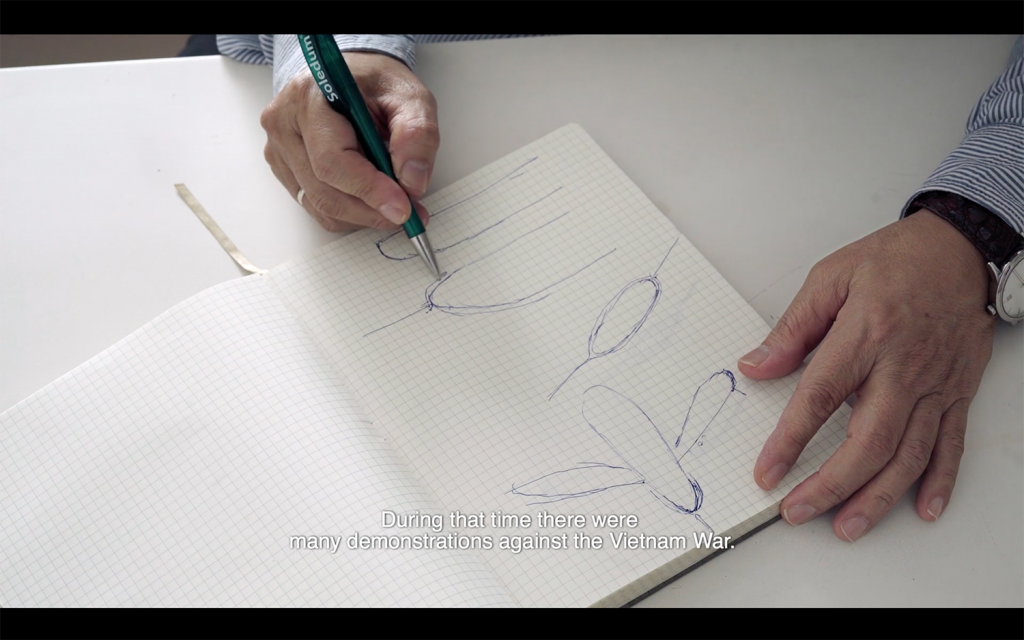

In ‘Syncrisis’ (2018), the viewer sees a ping pong table on which a ball eerily bounces back and forth with no visible players, in the middle of a night-time forest. This sense of hauntedness pervades throughout the exhibition, as preternatural phenomena, as references to signs of former life, as phantom flashes in multi-layered videos. Footage of the infamous self-immolation of the Vietnamese Mahayana Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc is layered with other cinematic samples and narrated with a voice over of Nguyen-Chi’s father describing how he witnessed the event first-hand , ultimately changing his political orientation. The stacked accounts of the same event evoke the way history comprises an infinity of traces, and that one’s memories are complex assemblages of their own experiences along with the prosthetic memories of family narratives and mass culture.

Nguyen-Chi’s hallucinatory filmmaking style asks us to imagine perception as less regulated by prescribed rules. We are presented with tapestry of senses, of disembodied voices and undeterminable sounds and visions. In its dissolution of a narrative on or off-screen, it questions how narrative powers of history are sustained, and suggests how to dissolve them. In response to Nguyen-Chi’s exhibition, I treated the work as a letter from the artist, and returned the correspondence:

Dear Han,

Lately I’ve been thinking about living as circling. It seems like the silver wire of our lives are twisted in a coil, a sequence of rings. We find ourselves where we’ve been before, double- checking spots for something lost, reentering dead ends by mistake. We come and come back.

I listened to the audio file you emailed me, the clip of you and your father speaking Vietnamese. You described it as a weaving. The tonal soars and dives in your voices are a song that’s inscribed in my body, one that will long outlive me. I curled up in it. There is so much to talk about and there is also too much talking. Isn’t the promise of sharing language to plan for escape? Funny, when instead it burrows us deeper in the labyrinth. It’s like we forget we’re looking for the exit and instead analyze the idea of exits and the idea of looking, until the cold light dims to conclude another day and we fall asleep in the middle of the maze.

Do you think a family is a group whose mouths form the same shapes? Do you think a nation is a group who learns the same poem? Like Truyen Kieu, the Vietnamese epic poem about a woman named Kieu who had to sacrifice herself to her family, written in 1820 by Nguyen Du. People know it by heart, recite it casually to account for the unripeness of persimmons at the market, or to apply ointment on a senselessly violent past. The story explains that we, like Kieu, are predestined to endure pain.

It is so much easier to imagine dying for love than living for it. I love how Trinh T. Minh-ha adapted Truyen Kieu in her film A Tale of Love and dissolved the original story, moving Kieu across narrative zones. She created a version of Kieu that shredded her way out of the bound pages of the thousand Kieus before to escape to a dream place where she read and wrote, loved and lounged. It taught me about film as a wormhole, a psychic eyelet to where a secret Kieu lives and where we could live too.

You named the chapter on your father in ‘Syncrisis’ ‘The In/extinguishable Fire’ after the Harun Farocki piece. Farocki’s piece really moved me. Rather, it moved me in the way it didn’t move me. In the video, Farocki reads a letter by Thai Binh Danh, a survivor of an American napalm attack in Vietnam in 1966. He looks into the camera to ask, “how can we show you napalm injuries? We can give you only a very weak representation of napalm’s effect”, then burns the end of a cigarette into his forearm. I watched Farocki burn himself and instead of considering the hell-scorch of napalm burn (this consideration is, like the Vietnamese language, inscribed in me), I instead thought about what it means to see but not feel Farocki’s burn. This is what concerns me about the world of images: we see so much fire and are convinced it burns us but we stay unburned. Seeing the harms of fire will spread awareness of fire’s harm, people argue, but who needs more proof that the world is burning?

In ‘Syncrisis’ there is a part where your father describes seeing the self-immolation of Thich Quang Duc with his own eyes. Can we look at the photograph of the burning, look at every photograph of everything our parents have seen, and know what they know? I slip on the oily bridge between seeing and knowing. I look at the famous photograph that Malcolm Browne took, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize and the World Press Photo of the Year. In photojournalism, a prize-winning photograph is called a ‘carrion hunt.’ This too is my concern about the world of images, that it makes voyeurs of us, makes us assess everything as an aesthetic capture.

What does it require of us to not capture, to hold things with a lighter hand? How can we be truthful, as Minh-ha writes, when being truthful is being in the in-between of all definitions of truth? There’s much more I could say to you, but in another time, so instead I’ll tell you this. There is an unexplained phenomenon among some marine animals called ‘natal homing’. When sea turtles become scattered across the vast ocean, they attempt to swim back to the place they were born to reproduce. They use the earth’s magnetic field as a directional cue, deriving positional information from two elements, ‘inclination angle’ and ‘intensity’. Maybe the next time we feel the pang of cosmic lost-ness, we can figure out where we need to go by thinking like sea turtles. We could try asking ourselves, ‘what inclines our lost-ness?’ and ‘how intense is it?’

Yours in spiral,

Minh**

Thuy-Han Nguyen-Chi’s What My Eyes Behold Is Simultaneous solo exhibition was on at Chicago’s SITE Galleries, which ran March 29 to April 20, 2019.