Shevaun Wright is suing Eli Broad. The Australian-born, Los Angeles-based artist’s recent thesis exhibition, Class Action, is both an active litigation and a conceptual presentation that contests the very name of the site in which it was installed: The Broad Art Center at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Presented for only one short week, from March 7 to 15, the minimalist installation featured material from the artist’s lawsuit against the multi-billionaire entrepreneur and philanthropist, who was officially served in person on the last day of the show.

Class Action doesn’t depict, it enacts. It cites Broad’s alleged attempt in 1998 to embezzle funds from a Leonardo da Vinci manuscript sale meant to benefit the Hammer Museum. At the time, he was an active member of the art institution’s board and considering a donation to fund a new arts building at UCLA—under the condition it be named in his honor. Acquired in 1994, the Hammer serves as both an extension and home to the university’s collections and staff. A few years after the partnership was announced, the museum’s newly appointed director, Ann Philbin, successfully thwarted Broad’s attempt to misappropriate $10 million from the Da Vinci sale, leading him to step down from the board. Despite his actions, Broad donated money to the university, and secured his name on the building. The claim—the legal element of the art work—requests that UCLA remove the names of Eli and his wife Edythe Broad from the School of Arts & Architecture building due to a breach of the university’s ethics policy and for unjust enrichment. Class Action therefore contests the very location in which it was installed, while illustrating the legal and psychological implications of allowing Broad to retain any connections with an institution he personally tried to undermine.

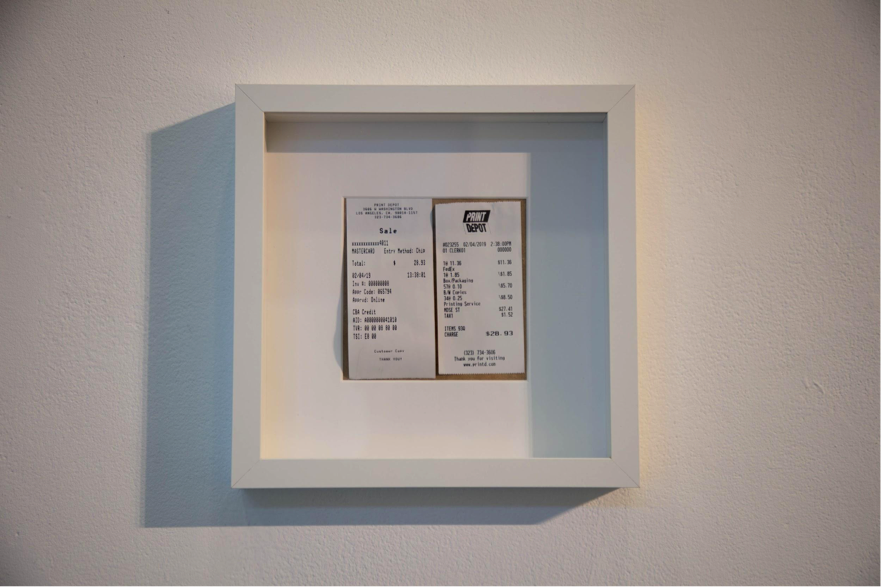

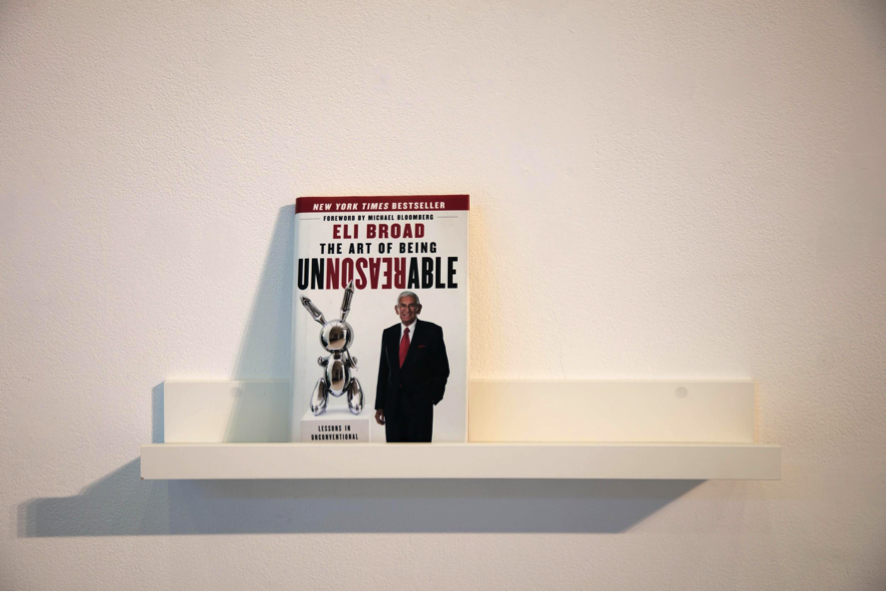

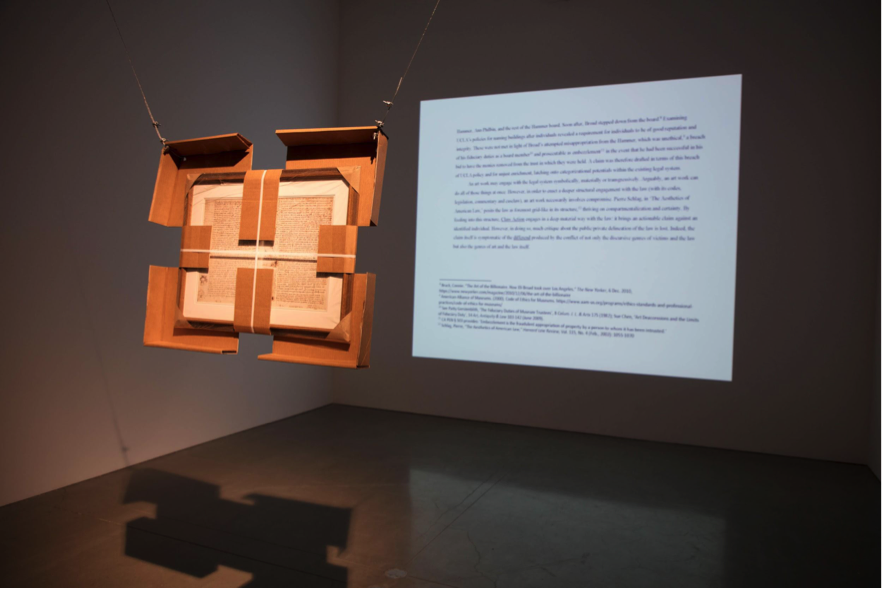

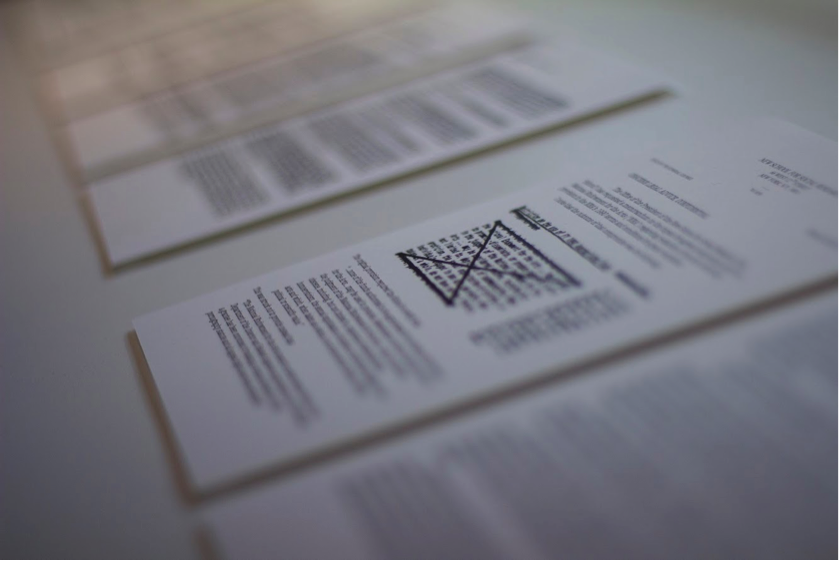

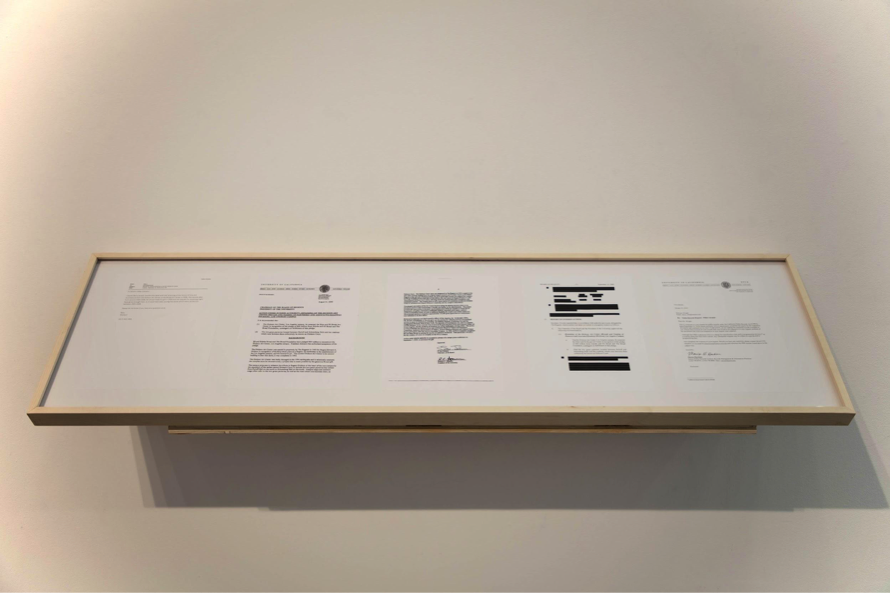

The installation details the legal and ethical ramifications of naming UCLA’s School of Art in honor of the Broads by including all the documents and research material supporting the litigation. Letters, replica plaques, a book, print and the original FedEx receipt procured upon mailing said letters are presented within the first part of the gallery. Around the corner, a framed copy of the original Leonardo da Vinci manuscript is suspended from the ceiling, behind it a projection displays pages from Wright’s thesis. Each work is titled according to the legal and philosophical proceedings accompanying the case: ‘The Naming’, ‘Restitution’, ‘Name-of-the-Father’, ‘Le Nom Du Père’, ‘Response I (Eli Broad)’ and ‘Response II (University of California’. That is, with the exception of Broad’s own 2012 book title, The Art of Being Unreasonable. On opening night, Wright included copies of both the litigation letters, as well as a detailed map of the exhibition, which served not only as physical guides to the works but also as theoretical musings and side notes. On the first of the four page guide, the text from the original plaque is included, with a quote from Broad himself: “Contemporary art challenges us… it broadens our horizons. It asks us to think beyond the limits of conventional wisdom.”

For Wright, law is an artistic medium. As a trained lawyer practicing in Australia until 2015, art became a way to explore the limitations of the legal system by giving voice to those caught within it. After years of art studies in both her native Australia and the US, she now assumes a duality that allows her to investigate the often-misconstrued boundary between representation and performativity. Locating herself both within and outside the very systems she challenges, she collapses the conceptual with the legal; critique with action. The contract becomes an active tool that reveals not only the failings and fictions that operate within the law but also the means with which they’re disguised.

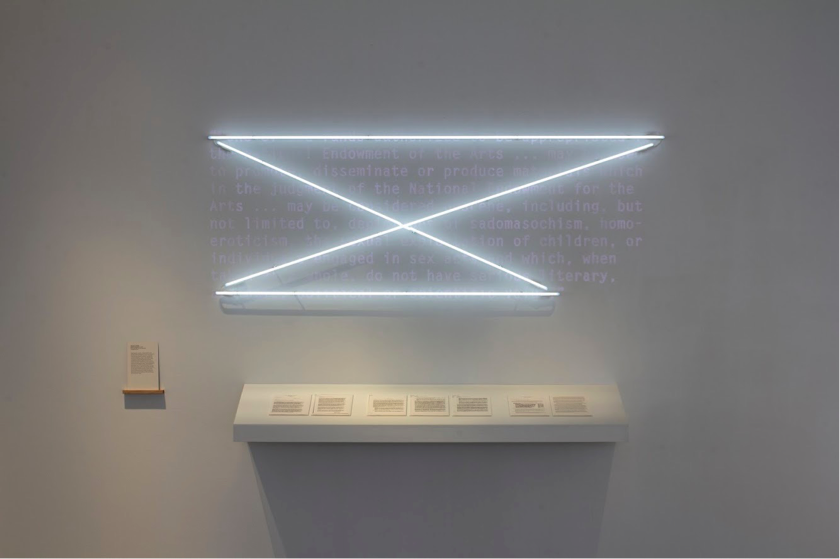

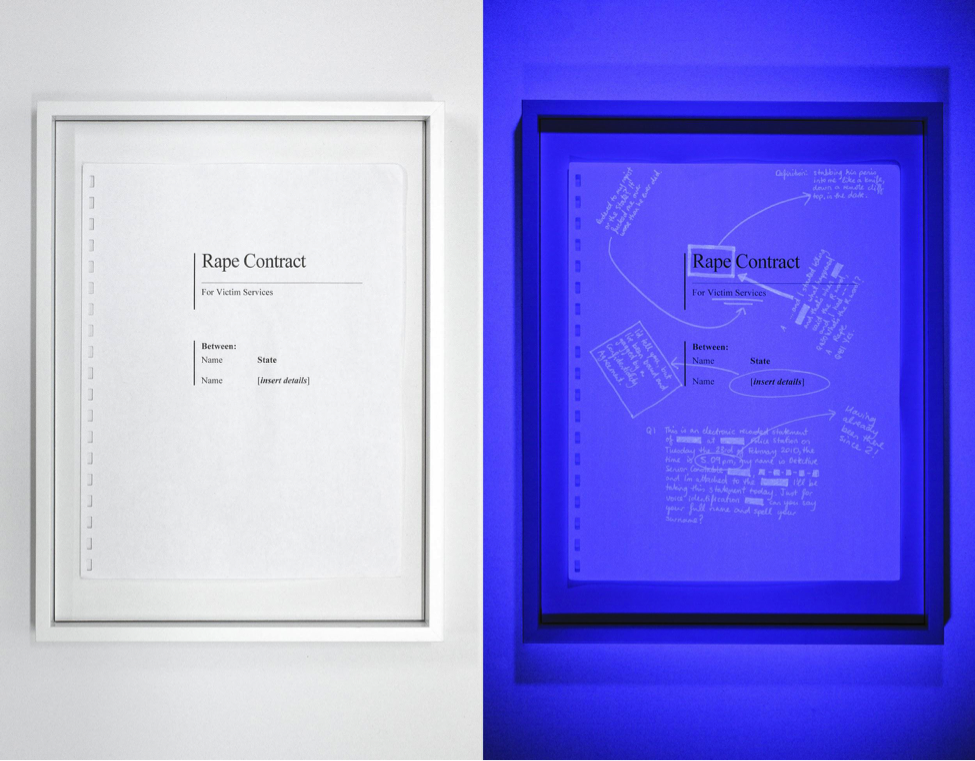

In her 2017 work, ‘The Rape Contract’, Wright introduces a victim’s personal account of assault onto a legal document by writing the notes, and psychiatric and police statements in invisible ink. Her most recent ‘Double Redaction’ work, now on view as part of The New School’s In the Historical Present group exhibition, renders a clause that was inserted into standard National Endowment for the Arts contracts during the 1990 culture wars. Making a fallacious association between obscenity, homoeroticism and child pornography, the NEA clause is illuminated by Wright through archival documents, paint and a neon light in the shape of a strikethrough. Similar to Class Action, ‘Double Redaction’ is site-specific. The clause in question was challenged and ultimately settled by The New School after it received an NEA grant, but never removed.

Class Action stands out, not only for its timely rebuttal of corrupt academic systems but because it reveals a different kind of thesis. Both Wright and Broad activate the same mediums (art and law) but to opposite ends. Where Wright unveils with law, Broad uses art as a legal mechanism to advance his own power and legacy over the city of Los Angeles. As Wright awaits Broad’s answer, we sat down to discuss the project, the relationship between art and the legal system, and what she hopes to achieve with Class Action.

**Your work is concerned with the boundaries between fact and fiction, representation and performance, and the subject of the body. Specifically, the marginalized, oppressed and violated body. Before making art, you were a practicing lawyer in Australia, a field you no doubt approached due to your own experience as a white woman of Aboriginal descent and a fact that also informs your art practice. How did you begin making work, and when did you decide that law was a better medium than discipline?

Shevaun Wright: I started making art in school as a postgrad, when I was already practicing law. I began with painting. At first the works weren’t directly working with law, they were mostly paintings of portraits, essentially an exploration of texture rather than a political statement. It wasn’t until I was shown contemporary aboriginal art that I realized how powerful art could be. I saw Vernon Ah Kee in the National Gallery of Australia and that was when I realized that you could actually mobilize art for political change. He had done a portrait of someone who couldn’t be depicted in the news because he was in jail for political reasons. What the law had forgotten to bar in the suppression order was depictions in art of this person.

**So you saw art as a kind of slip through the legal system…

SW: Yes, it was. I was really moved by it. It was really powerful because the person who was the subject of the drawing (that Vernon had made) couldn’t come to the opening. It was then that I realized the potential. Soon after that I made my first piece, which was a fictional contract about colonization in Australia. And it kind of just went from there.

**Since then, you’ve continued to use the contractual medium throughout your practice, yet you’re always manipulating it. Do you feel you have more of a voice as an artist working within these legal terms because there aren’t the same binding contracts, or rather stipulations, that you would find otherwise? Do you find you have a different kind of access?

SW: Yes. There’s so much that you can say in art that you can’t say in private practice. Early on, one of my artworks was shown in parliament, in New South Wales, which allowed me to meet politicians and also influence a bill that was being decided on at the time. The senator behind the bill, David Shoebridge, was trying to extend the time limit for historical child sexual abuse so that victims could seek compensation beyond the usual cutoff. There was a flyer I was giving out as part of the artwork, and after speaking with David, he gave those out to other senators as they were debating the bill. And it ended up passing. It was a kind of access to a site of power that I hadn’t had before, and a platform that I had not had as a lawyer.

**So you were able to show the artwork within the actual legal context it was debating, which is very similar to Class Action. Like the parliament work, the action of the artwork- suing Eli Broad- takes place within the very context you’re challenging, which is the name of the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Center at UCLA. How did this project begin?

SW: I was not initially drawn to Broad. I was initially drawn to synchronicities that came up when I was researching the history of the site, where the gallery is, and some legal cases I was researching, as well. What started to emerge in the research was how the law navigated what it thought was private and what it thought was public.

**How did you get to that point?

SW: The research started to revolve around the year 1994, when the UCLA building was damaged in the Northridge earthquake. Within a few months of the earthquake, the Violence Against Women Act was passed, and a few months later, United States versus Morrison took place. That was the case where Christy Brownkala, the Virginia Tech student who was raped on campus, sued her attackers under this recently passed legislation and lost because it was found to be unconstitutional. Her attackers challenged the constitutionality of that clause on the basis that Congress had exceeded its power when it passed that law. What was really interesting about the Morrison case was that the government ended up trying to argue that it did have the power to pass this law, not under the 14th amendment but under the commerce clause, because gender-based violence affected interstate trade, which therefore gave it jurisdiction over the issue, which is really absurd to me.

**For real?

SW: I’m not making any of this up. I then looked at who donated money to fix the buildings on campus, and the biggest donor was Broad. I then came across an article that revealed Broad had tried to misappropriate money from the Hammer Museum, and it went from there. [The research] was dealing in synchronicities, coincidences, numbers, timing. It was not initially about Broad at all.

**Class Action included documents that both demonstrated the act of serving as well as the research that led to it. Yet, while most exhibitions start and finish, yours is ongoing.

SW: It is. Broad has been served; he’s not responded. Neither has the president of the University of California. I’m contemplating the next steps.

**Regarding the subject of private and public, are you going to make the remaining part of this case legal?

SW: I think if I was to publicly talk about the next steps, it would be to not take seriously the legal strategy behind it, because often when you have a claim you don’t discuss something that’s afoot.

**And yet you’ve made everything public thus far by exhibiting the documents, printing the letter and distributing it, speaking with me. Not publicly talking about it will allow Broad to dismiss it purely as being conceptual art.

SW: I think he already has. I can’t say exactly what he’s thinking, but I’m sure he’s treating this like an art project at this point. Possibly the President of the University of California, as well.

**I can’t help but wonder… Do you think of it as an art project?

SW: Yes, I do. I want to pursue it but I do think of it as an art project.

**Let’s say, hypothetically, the case continues and it becomes a big headline in the press. How would you move forward, would you affirm your position as an artist or a lawyer?

SW: I’d have to do it both.

**News media and society will undoubtedly pit the two roles against each other. How would you negotiate that process?

SW: I would have to cross that bridge when I came to it because there’s also the issue of navigating how things are imported—you don’t always have control over that. I mean, Connie Brooks’ article in the New Yorker in 2010 was a really strong article and I’m not sure how many shock waves it actually sent through LA. It’s a serious thing to try and misappropriate money from the Hammer.

**It is, and whenever I’ve mentioned this project to anybody in the art world, most people are very familiar. It either gets a familiar knee-jerk reaction, or an eye-roll. It seems to be old news. And yet despite it being old news, we’re living in a moment in time where old news is becoming new again for the simple reason that we have a younger generation telling us it’s fucked up. None of us are surprised; the information just needs to be re-analyzed. But Class Action is also a testament to the failing system of academia within the ‘States, and the fact that capitalism and academia are in bed together.

SW: It’s definitely representative of broader issues. It is an interesting time, especially with the Sackler controversy and with what’s going on with the ‘Varsity Blues’ cases, and the fact that UCLA is a public institution…

**And yet most places that are public feel very private. I was surprised to learn that UCLA was a public school after I moved to LA. The campus, the architecture, it all feels very private.

SW: They are very privately funded. I mean, the building is named in perpetuity after. So that’s a very long time to have your stamp on a public institution. At the time, I did some research around the psychology of naming and what effects that has on people—all of which is included in the litigation letters in the thesis—and there can be long-term effects. There were studies conducted that looked at the effect of naming on people’s conceptions of their self, and also relationship to that name. Essentially, love and affection builds towards a name when it becomes a regular association. So to have an art school named after Broad, and then also have Broad be such a prominent figure in the arts, does have an effect on the student body, I believe.

**Is this project aimed at a particular audience, such as UCLA students? Or is it more about reparation for past wrongs, about revealing the fictions and failings of law?

SW: It’s aimed at the general public. While it’s primarily a discussion about the art community, it’s institutional critique. What I hope to achieve from the project is a discussion about the role of philanthropy in public institutions, particularly art..**

Shevaun Wright’s ‘Double Reaction’ installation is part of the In the Historical Present group exhibition at New York’s The New School, running from July 8 to October 6, 2019.