This Summer, the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London is holding the first UK exhibition dedicated to the American writer Kathy Acker (1947-1997), I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker running May 1 to August 4, 2019. The exhibition is structured around fragments of Acker’s writing, serving as catalysts for a network of interconnected materials presented around them, including works by other artists and writers including myself. Written in response to the exhibition, this text is specifically not about Kathy Acker. It is about the unprecedented insurgence of marginalised “British” writers making connections between literature, critical theory, art, performance, fashion, politics, and queer, working-class and diasporic cultures and lives rn.

Kathy Acker’s use of the first-person singular may have been plural, but it wasn’t communal (or at least not in its effect). The mainstream success of Blood and Guts in High School when it was first published in the UK in ’84 did nothing to help advance British queer avant-garde writing more widely, not then, nor in the period afterwards (’90s/’00s/’10s). The conditions of possibility for queer and innovative writing simply were not in place. In her conversation with cultural theorist Angela McRobbie in ’87, Acker repeatedly refers to her status as an exception or token: the one postmodernist writer, the one writer connecting fiction with critical theory and subcultural contexts, the one transgressive writer in British literature at the time. Did Acker-tokenism in the ’80s and ’90s enable the publishing establishment to give the appearance of risk-taking and inclusivity, rather than make the structural changes required to address its elitism and normativity long-term?

The absence of a queer and intersectional British avant-garde writing movement to speak of 1980s onwards – or, hold on, ever – while in the US and Canada for example New Narrative happened can be put down to a variety of reasons. They include the entrenchment of class in British publishing and literature itself; the industry’s extraordinary resistance to change in the face of public demand and even profitability (this is meant to be capitalism and potential working-class readerships keep being disregarded); the gate-keepery at play; the Oxbridge; and the detail that early academic critiques of Cambridge English (for example Raymond Williams’) moved away from their discipline of origin and into the field of cultural studies where they did, actually, make a difference. Not so incredible, then, that the marginalisation of interdisciplinary working-class, LGBTQI+, Black and POC writers should be ongoing. Kathy Acker, herself from an upper-class background, remains the one transgressive, experimental writer widely represented in British art, literature and media establishment contexts. It’s like, I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker, arguably at the expense of everyone else.

Enabled by a combination of factors including the digital disruption of the publishing establishment, a proliferation of radical independent publishers such as Arcadia Missa, Dostoyevsky Wannabe, Ma Bibliothèque, Pilot Press, Pss, The 87 Press and Zarf, and – for better or worse – social media, writers including Mojisola Adebayo, Jay Bernard, Ray Filar, Caspar Heinemann, Niven Govinden, Hannah Levene, Juliet Jacques, Natasha Lall, Huw Lemmey, Abondance Matanda, D. Mortimer, Nat Raha, Shola von Reinhold, Alison Rumfitt, Scottee, Rosie Snajdr, Verity Spott, Linda Stupart, Timothy Thornton, Eley Williams and me, too, are redefining formally innovative writing as a medium which is helping to mobilise new communities online and irl, intertextual and personal. By “mobilise” I mean oversubscribed reading events in London and across the UK, I mean publications of stellar literary value which, btw, sell. The queer culture book fair Strange Perfume at the South London Gallery is in its second year, and so is Queers Read This, the reading series I co-curate with artist and publisher Richard Porter at the ICA, and that platforms interdisciplinary writers.

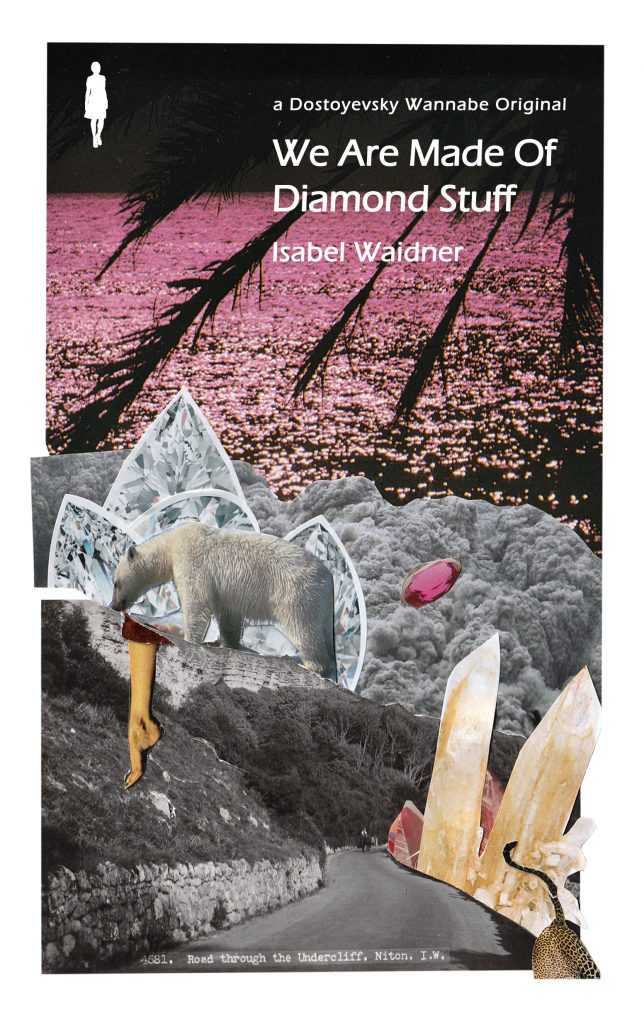

This text is me “peer reviewing” a carefully curated mini sample of two; Caspar Heinemann’s poetry collection Novelty Theory (2019, The 87 Press) and my own novel We Are Made Of Diamond Stuff (2019, Dostoyevsky Wannabe), via Abondance Matanda and US writer Kevin Killian’s work, plus the gossip. The purpose of this exercise is to introduce our work to Acker-loving, Acker-hating audiences, to challenge Acker’s status as the one, token experimental writer deserving of wider recognition, and to identify and map out some of the themes and preoccupations that obviously don’t define, but maybe get at interdisciplinary queer writing in Britain more widely. The rationale behind this particular comparative reading is based on real events (very soft facts): in March ’19, Caspar and I both read at Queers Read This at the ICA. Despite Caspar and I coming through very different writerly and academic trajectories probably, the affinities between their poem ‘Situationist International Airport’ (from Novelty Theory) in particular and We Are Made Of Diamond Stuff were too much, really, for them not to feel significant in respect to this current literary moment I’m trying to get a purchase on. Know that I’m 100% committed to replacing the pseudo objectivity of mainstream review culture with insider info.

We need an expanded review culture, ‘cause, whatever is going on in Guardian Books isn’t it. The inspiration behind my approach to peer reviewing is New Narrative writer and critic Kevin Killian’s work, specifically his Selected Amazon Reviews (2006, 2011, 2017). Published in three volumes, the Selected Amazon Reviews contain selections from 1000+ reviews that Killian left on Amazon.com, amounting to, according to one publisher, “a subversive and delightful modification to a pervasive online art form.” Reviewed items range from Buttmen 3: Erotic Stories and True Confessions by Gay Men Who Love Booty, Tender Harvest baby food (“its soft, piquant flavour”), a self-help book by avant-garde novelist Dennis Cooper’s father Clifford D. Cooper, to poetry collections by John Wiener, for example. What’s funny about Killian’s Amazon Reviews is also strategically and analytically on point: Engaging with text as well as with the cultures and politics in relation to which it emerged, writers’ bios including their love lives, degrees of separation, tangents and half-truths, Killian’s personal and chatty reviews provide crucial context for anyone, researchers, me, trying to get a handle on the historically specific conditions of possibility for queer avant-garde writing (and Buttmen 3).

In their wild disregard of high and low culture distinctions, Killian’s reviews are re-defining what even merits a review – and by extension, what literature actually is. South London writer Abondance Matanda’s essay ‘The First Art Galleries I Knew Were Black Homes’ (2017), which is key in terms of what “British” working-class avant writing should be doing rn, makes a similar point more explicitly. Not only does ‘First Galleries’ place family photos, glassware and the dusted china in her mother’s front room – “that shit you could never touch” – alongside proper art objects held in the Tate, the V&A, the White Cube, but also alongside the fashion of Black-owned London label A-Cold-Wall*. A-Cold-Wall* designs derive from working-class references, reminding Abondance of the blue plastic bags from the corner shop which she ties round her head when it rains and she got no umbrella, of pebble-dash and concrete, of white lace curtains billowing in the breeze, “translating it all into grandeur somehow.” Crucially, Abondance *does* to the essay form what she *says* about art – combining colloquialisms, whatever, youth speak, and critical acuity, she literally claims it and makes it Black working-class, South London, diaspora.

Stretching the rules of grammar like Abondance stretches the essay form, Caspar Heinemann writes: “Last summer I got in an argument in a sauna with someone who said she would hate to edit my work because I use or maybe am too many forward slashes and apparently the new narratives of the coming collapse or white flight or whatever must be formally grammatically correct.” Likewise, peer review culture as I envisage it is too many forward slashes, poised against the conventions of mainstream literary reviewing, or, to quote the White Pube’s Zarina Muhammad, “the typos are part of the experience.”

Caspar’s ‘Situationist International Airport’ is a poem two pages long, projecting queer avant-garde potential onto the legendary English seaside town Blackpool. Caspar’s protagonist, “a young man cruising the charity shops”, is maybe a take on themselves, looking for something cute to put on. In contrast, or I don’t know, similarly, We Are Made Of Diamond Stuff is an innovative novel, set on the Isle of Wight off the south coast of England. It collides literary aesthetics with contemporary working-class cultures and attitudes (B.S. Johnson and Reebok classics), works with themes of empire, embodiment and resistance, and interrogates autobiographical material including the queer migrant experience. My protagonists, Shae and someone who looks like Eleven from Stranger Things but who’s actually 36, work in a decrepit hotel in the small town of Ryde. They’re 100% up against it, but, according to Dodie Bellamy’s blurb of the book, they “survive, not just physically but spiritually as well.” Both, Shae and Thirty-Six are versions of myself 6 or 7 years ago, survival ongoing.

1) The first common denominator in ‘Situationist’ and Diamond Stuff is seaside towns looming mythical in the British psyche. Caspar’s “glittering situationist internale blackpool | truthfully closer to pre-gentrified margate” is my diamond Ryde. Some background: L, my real-life partner, is a Portsmouth working-class. Growing up in the ’70s and ’80s, L regularly spent family holidays on the Isle of Wight, winning the Disco dance competition at Thorness Bay Holiday Park, treasuring miniature bottles of multi-coloured sands from Alum Bay. What’s potent perhaps about seaside towns as a literary setting rn is how English Riviera mythologies clash with the realities of a tourist industry in decline since the ’70s charter flight revolution at least. Spain is – or was, prior to the referendum-related slump in the GBP – cheaper. Any long-term decline has been exacerbated by governmental neglect since 2010. Dereliction is real on the Isle of Wight, and presumably Blackpool. Place is falling to pieces, the shops on the High Street are shut, half the town is on the sick or the dole or has fallen through the crack formerly known as the welfare system. The Georgian villa, though, in that really out of the way posh part of the island is a-ok. Passed down the family through generations, no one’s in it much anymore. Worth holding onto because sea views. No point selling, not in the currently fcked economic climate. Ride out Brexit. Might go over Easter nxt year, avoid terrorism abroad. Beyond containing Tory reality and holiday fantasy in one body, then, British seaside towns are fully-formed microcosms of class inequality – maybe that’s why we’re setting everything in them.

But in both, ‘Situationist’ and Diamond Stuff, Blackpool and Ryde don’t just stand for endemic underfunding, high unemployment rates, former glamour and old Etonian money, but for imperialism per se. One of the thematic strands running through Diamond Stuff, for one, is the embeddedness of empire not just in the British psyche, but in the Isle of Wight’s actual infrastructure and landscape. With countless prehistoric forts in the surrounding sea (against the threat of a French invasion), the island’s proximity to Portsmouth harbour (home of the English navy since the Middle Ages), its role as a key site of defence in the Second World War, and the physical ruins of the British Space Rocket Programme (1950s-71) left on some cliff, imperial violence is basically one with scenes of natural beauty down there. Imperial violence is literally naturalised, which can play wth your head. Blackpool might not share the Isle of Wight’s military history, and Novelty Theory might not talk empire to quite the same extent, but it’s there in austerity Blackpool, its crumbling ice rink, the queer phobia, the being a foreigner. In another poem from the collection “they have no evidence that asylum Europeans or Eastern seekers are responsible for reported reductions in the swan population”, Caspar writes that “the last scraps of empire [are] leaking sort of justified apocalypse.” We knew what we had coming and it’s sort of deserved.

Caspar and my seaside towns have this redeeming feature, though, they are laying bare barely repressed gay potential. Blackpool and Ryde are GLITTERING! DIAMOND! BLEAK CRYSTAL! GLITZY!! Many have claimed that the sea is queer – something something liminality and fluidity, I don’t 100% get it but ok. Something Jean Genet, sailors and sin, and something about ports as historical sites of lewdness and transgression. Caspar’s protagonist appears to escape familial phobia elsewhere (“before i know it i am | being told to sleep outside the family | home next to the patio heater for being queer”), to destination situationist Blackpool. According to L, venues including the now demolished Tricorn Centre, a brutalist shopping, housing, nightclub and car park complex in Portsmouth were subcultural hubs in the ’80s, with traces of these histories still visible in the suburb of Southsea at least, home to the Hovercraft terminal Southsea-Ryde. In contrast, L says that every time a naval aircraft carrier landed at Portsmouth Harbour, sailors and their rampant, aggressive, patriarchal heterosexuality descended onto the local clubs and bars. Business would be good for the sex workers travelling in from the surrounding towns, so that’s a positive – but for a lesbian or afab youth growing up in the area, it was best not to go out in the event of shore leave.

In David Hoyle’s first feature film Uncle David (2010), a young gay called Ashley (played by the porn actor Ashley Ryder) arrives to stay with his Uncle David (played by Hoyle). Uncle David enters into a sexual relationship with Ashley. Ashley tells Uncle David that he wants to die, and Uncle David agrees to carry out the killing. The film is set in a caravan park at what I wrongly assumed was the coast near Blackpool (because David Hoyle is from Blackpool), but what turns out to be the Isle of Sheppey in Kent! Blackpool or Kent, the seaside in Uncle David is queer, lewd, cheap, funny, intimate and murderous, unless that’s just David. As metaphors seaside towns hold antagonisms, and so does the best contemporary writing and art: queer potential sits with phobia. Openness to outsiders sits with misanthropy. Dependency on the tourist industry sits with xenophobia and racism. The limitlessness of the sea sits with military defence structures, boulders and border controls.

2) Queer culture is… getting my new book featured in the Financial Times and it being accompanied by a stock image of white people at Pride, flying the rainbow flag (true story). Both, Novelty Theory and Diamond Stuff look at queer cultures, specifically the appropriation of queer cultures by the straight mainstream, but also mainstream LGBTQI+ culture and its twin things, homonormativity and gay assimilation. In Novelty Theory’s ‘Baths Suck’, Caspar quotes eco-feminist Françoise d’Eaubonne who writes that “it’s not a question of integrating homosexuals into society, but of disintegrating society through homosexuality”, expressing Caspar and my shared perspective that queer politics if you want to call them that must be transformative of society at large. In Diamond Stuff, the rainbow flak – I mean, flag – is taken to task as a symbol of increasingly reactionary mainstream LGBTQI+ politics. Caspar even asks that “someone get [them] a fucking umbrella to protect against the UV of umbrella identity formations!” Finally, “FUCK CORPORATE PRIDE”, capital letters, in Novelty Theory. Sums it up.

3) Relationship with the historical avant-garde: complicated. Another concern which connects Caspar and my books is a shared investment in, but disappointment with, the promises of the historical avant-garde. ‘Situationist’ references various avant-garde traditions incl. “our avant guarded bearded bespectacled ancestors of the concrete poetry may 68 glitz”, Dadaist Hugo Ball and, obviously, Guy Debord and the Situationist Internationale organisation. Diamond Stuff, too, makes links to avant-garde histories, and what’s more, it tends to be read as an extension of a genealogy of experimental literature. According to a recent write up in Tank Magazine, for example, Diamond Stuff “tips its hat to the author B.S. Johnson, whose 1971 novel House Mother Normal gives this book its formidable villain.” “In this”, Tank Magazine continues, “Waidner aligns their work with a generation of postwar experimentalists exploring class and culture with a camp and baroque cleverness.” ☺ But my relationship with the avant-garde literary canon is far more complex if not unhappy than this reading suggests: Diamond Stuff is designed as an intervention against the normativity and elitism of much of English-language and European avant-garde literature. House Mother Normal might be one of the villains in Diamond Stuff – but another villain might be B. S. Johnson himself!

The concern of what, if anything, contemporary queer writers might take from a canon that is largely white, male, cisgender, heterosexual, middle-class and totally commodified, is one that at least partially shapes the contemporary literary moment more widely. In relation to historical avant-garde literatures I’d say that my own writing practice is disidentificatory – a practice enacted by a minority subject (me) “who must work with/resist the conditions of (im)possibility that the dominant culture (in this case, the avant-garde canon) generates.” (Muñoz, 1999) Aligning myself neither with, nor fully against canonical works of avant-garde literature, Diamond Stuff puts these works (e.g. Johnson’s) into dialogue with work by contemporary writers from marginalised backgrounds including Mojisola Adebayo, Jay Bernard and Nisha Ramayya, as well as pop cultural references like StrangerThings and I, Tonya, transforming historical avant-garde literature (Johnson’s) for my own cultural and political purposes in the process. Similarly, Caspar ferries Walter Benjamin into Blackpool’s charity shops. They ship Hugo Ball, Guy Debord and the situationist “internale” into “this bleak crystal sea side town that is ours | through a portal it has always been ours” – for my purposes I’d interpret that to mean that it requires a lot of passing through portals and disidentificatory labour to actually own the stuff that should’ve been ours to start off with.

4) I mentioned the “portal” in situationist Blackpool – Nr 4 is parallel universes. In Novelty Theory’s ‘They No Vision Saw’, Caspar writes: “the hospital i was born in no longer | exists due to funding cuts | but there’s still the big austerity-proof | hospital in the sky.” Interesting given the state of (post) austerity Britain, the big what-if in the sky is a key dramatic device in both, Novelty Theory and Diamond Stuff, and arguably characterises a particular queer mode of writing more widely. Maybe it’s the proliferation of Netflix series like Stranger Things and The OA, maybe we’re desperate for alternate realities, I don’t blame us. My chapter ‘The Upside Down’ describes a parallel dimension where everything is in the sky and potentially better – but is it. Entering the Upside Down, Thirty-Six spots a pair of gay British lions in love, gets to hang out with Shae’s estranged parent, encounters a version of Shae who isn’t a school drop-out, discovers quality social housing in Central London, and even receives British Citizenship which she is refused irl. “i don’t even need to live here!” Caspar’s young man rebuffs their phobic parents in ‘Situationist’, pure bravado. “i earn a million pounds a year! | so business must be good in situationist international blackpool.” Everyone knows business is the actual worst in real-life Blackpool, but poetry Blackpool maybe takes millions.

The mobilisation of a less than depressing future in the face of no hope or no deal was always going to be crafty. In order to maintain a half-plausible relationship with reality, imagined possibilities literally have to be relegated to parallel dimensions maybe – ‘cause, it won’t be happening here. We’re realistic in Britain. The project to somehow, we don’t know how exactly, write credible modes of resistance while running out of options is probably at the heart of interdisciplinary queer writing atm. In Diamond Stuff, even the Upside Down ends up turning bitter – the fantasy can’t be sustained, not under the circumstances. Not in Tory Britain, no way.

Other pitfalls of twenty-first-century life featured in Caspar and my books include eczema, every imaginable autoimmune condition, histamines flying around, and the possibility of undiagnosed Lyme disease. Ecopolitics, nature and the climate catastrophe are central to Novelty Theory, less so to Diamond Stuff – I have internalised this thing that nature is middle-classed and militarised, I’m also allergic. Apparently, Blackpool gets its name from a historic drainage channel that discharged discoloured water into the Irish Sea and formed a black pool, so there’s always that.**

Editors note: This is an edited version of a longer text ‘Class, Queers and the Avant-garde’ commissioned by the ICA on the occasion of the exhibition I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker at London’s ICA running May 1 to August 4, 2019.

Caspar Heinemann’s Novelty Theory is available via The 87 Press and Isabel Waidner’s We Are Made Of Diamond Stuff via Dostoyevsky Wannabe.