“What I always strive for is to get lost in the group,” says Berlin and Prague-based artist Lukáš Hofmann in a noisy cafe next to London’s Design Museum, where he’s just been to see a show called Dwelling. The self-confessed nomad is an artist who often brings other equally itinerant friends and peers together into performed moments of intense physical interaction. “It comes down to this almost fetishistic appreciation that I have of personalities and people. There’s nothing I love more than to be surrounded by people whose presence fills the room. I just expand and multiply this by having so many at once during the performances.”

Still relatively young, 26-year-old Hofmann is the most recent winner of the Czech Jindřich Chalupecký Award in support of visual artists under 35 years of age, having already developed a strong and recognisable aesthetic in what is a consistent body of work. Through sculpture, performance and styling, he tests the boundaries and potential of intimacy and expression. In 2017’s ‘Dry Me a River’ and ‘Enzyme’, performers dressed in torn and partial garments executed a demanding vocabulary of movement against heartfelt 90s pop and music by Simon.e Thiébaut. The audience was drawn into a ritualistic space where performers move between internalised and externalised meditative states. They enveloped one another, held their breath to the point of suffocation, offered themselves as deadweight to be carried and sounded as a choir. The result was an oscillating sense of both presence and absence within the group dynamic.

At a glance, this gasping and drenched clan enact separation issues, fears for the future, feelings of ineptitude and desensitisation. It is perhaps also emblematic of Hofmann and his contemporaries’ precarious experience of working in the creative industries who, untethered from a home, find friendships in wider circles as they gig around an increasingly uncertain Europe. However, within what appears anxious and strained, the artist provides a counterbalance effect of amusement and explorative play. These movements analyse the limits of a constructed reality and sense of self in order to reveal or will an alternate in which we have the power to act. The liberatory quality of group expression is then reinforced by the uniform dress devised by designers such as Anne Sofie Madsen, Ottolinger and an unwitting IKEA employee.

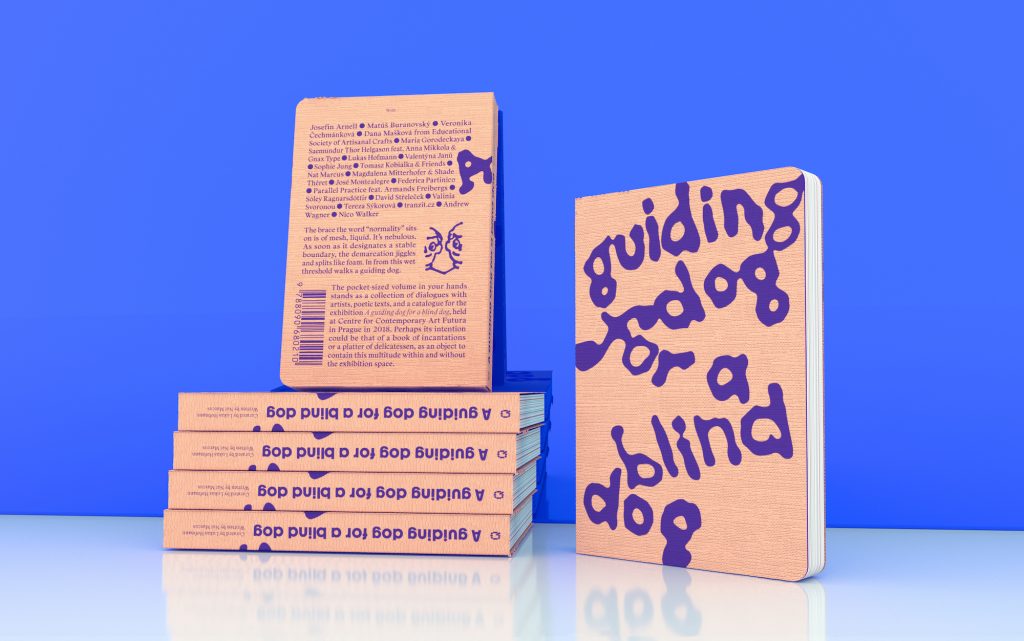

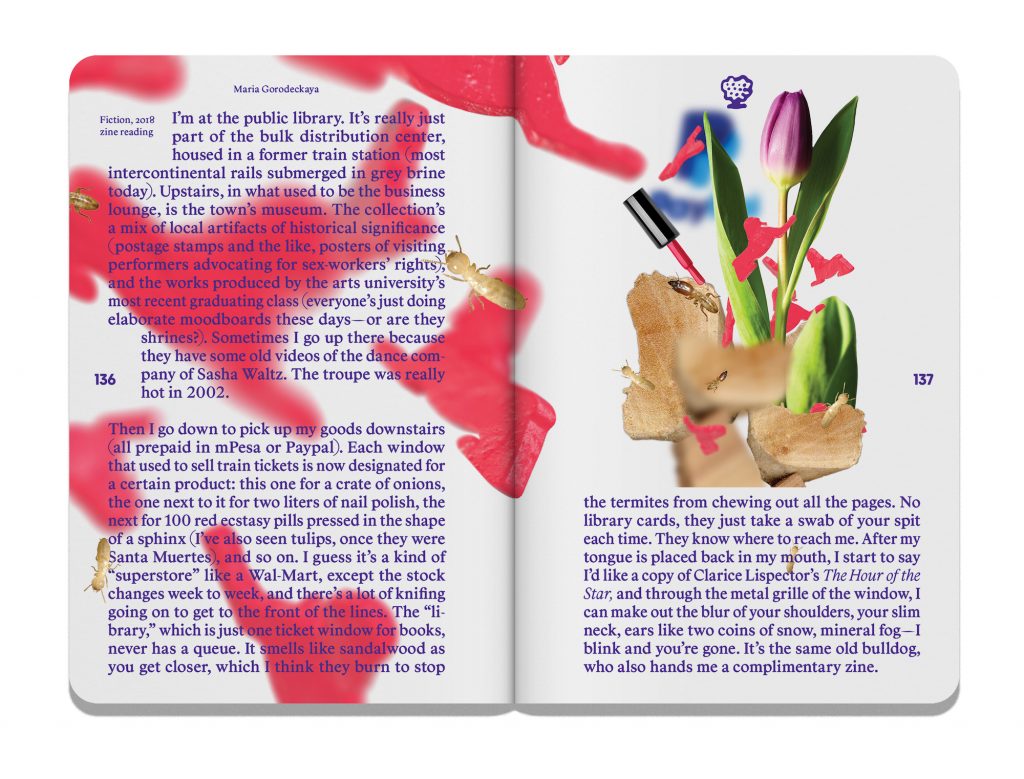

The conversation with Hofmann coincides with the release of his most recent book project, A guiding dog for a blind dog, published via Prague’s Futura Books imprint in February 2019. Produced in collaboration with the writer and poet Nat Marcus, the text stems from a larger exhibition of the same name presented at the Centre for Contemporary Art Futura last year. According to the press release, the concept extends his efforts to examine “reality’s soft scaffold—the truisms by which we knew it becoming damp, and possibly tearing” and sees Hofmann move beyond performance towards curation. Featuring artists familiar to AQNB, like Sophie Jung, Maria Gorodeckaya and Valinia Svoronou, the text is shaped into 28 short chapters, each one corresponding to an artwork or object in the original exhibition. Writer Marcus provides a poetic framework with his series of commissioned texts, Hounded, as well as an interview with each participant. Over a warming cup of tea, Hofmann enthusiastically describes the content of A guiding dog for a blind dog. There’s Saemundur Thor Helgason‘s lobby group and lottery advocating for a universal basic income, Tom Kobialka‘s explorations of the construction of desire in social media by harvesting like-farms on Instagram and Josefin Arnell’s family adventure into Brazil’s economy of healing. As opposed to creating a single unifying narrative, Hofmann’s book — much like his work at large — looks to build a multiplicitous realm of possibility and intrigue, reflecting a worldview that he extends, remakes and revisits ad infinitum.

**I came to know of your practice through performance works like Retrospective at Prague’s National Gallery. As a director, how do you work with others?

Lukáš Hofmann: People often ask me to what extent the result is an authentic or choreographed experience. Of course, the answer lies somewhere in between. This authenticity and inauthenticity, emotion, and suppression, and absence are very much the procedures that I work with. I have developed my own personal language now, like a dictionary or an emotional span of sentiment, atmospheres, and styling.

**I documented the rehearsal workshop last summer at Jupiter Woods during which you took participants through a number of the movements that you use in performance. It was really interesting to see a bunch of strangers get drawn into these increasingly close situations; blowing gently into an ear, providing mouth-to-mouth or attempting to lift someone up and carry them. What is the intention behind these exchanges (of breath, weight, etcetera)?

LH: There are lots of different mind games involved in this dynamic. One of the many points of this workshop-performance-happening was to establish a new agency and maybe a recognition of abilities that perhaps you weren’t aware of, some of which can be subversive, like a repulsion of acceptable social conduct.

To me, it’s a real-time active weaving of individual agency, as well as its suppression, alongside and within the dynamic of a group. It’s this elusive, effervescent and dense moment that’s quite difficult to talk about. However, what is incredibly important is absence. What my performance plays with — one of the main points of it — is the absence but also the healing element of absence. For instance, when the performers try to contain each other or an object, to envelop them, it stems from our will to potentiality, or to community but at the same time, maybe this incapability, or respect for someone’s personal space. It’s more striking to work with that than to just go around hugging people.

**Perhaps in absence there is a moment of choice, to choose to take part and be with other people. What is it about this heightened sense of intimacy that interests you?

LH: I’m one of those makers whose work is really representative of who they are. So when I’m working on something, it very much stems from the moment I find myself in. In my day-to-day and performative life, there is quite a stark difference in how present I feel. This is something that I do want to change. I go through life in this fairly unpresent state, things and occurrences seem interchangeable to some extent. They do leave a mark and I do have emotions but there is a kind of numbness that I live with. During my performance, that disappears. The biggest psychological benefit of the performance to me is to feel present. While there’s so much community/making in the performance, and it has a strong magnetic field, I wonder if that community-making agent one finds in my non-performative life?

**But what’s the difference? These are real friendships, these are real conversations. They are moments when people do come together — for the purpose of a public performance, ok — but it’s as genuine. Your community just isn’t local.

LH: This answers it better. Perhaps, I operate by creating these transient, temporary communities.

**Most of the workshop participants were being very smiley and reassuring towards one another. Whereas in the performances everyone takes a neutral position, is that intentional?

LH: It is intentional,but sometimes you can see spasms of physical pain in the performers. So while they are instructed not to over-dramatize, when someone tells you to lift your peer or be given CPR, you do go through physical pain. This dosage of silent aggression, this violent neutrality hiding the tumultuous inside stands in a central point of my work.

As a viewer, the strongest stimulus is perhaps when you realise that someone is having difficulties when their body starts uncontrollably twitching. Within the performances, many stories happen submerged like this, somewhere underneath in the mouldy and moist labyrinths of the less-conscious.

**What was your driving interest when inviting artists to take part in the exhibition and book, A guiding dog for a blind dog?

LH: Reading these dialogues and narratives, I personally can’t help but be fascinated by the colourfulness of the contemporary condition. That there are seven billion realities occurring simultaneously. Also the way in which we can live physically in the same place but the people you meet on the street have all these different belief systems. Nowadays, with social media, for instance, there’s just so much potential for externalization, the ability to connect with people on a different basis.

**….and if you’re really interested in a niche subject say, there is a like-minded group of people you can reach almost instantaneously.

LH: Or if you’re into disproving scientific methods, you can ascribe to the ideas of the flat earthers. Theirs was one of the many worlds that I delved into. Most of the participants in the exhibition were artists but others were not coded as such, for example, ladies who run an artisanal workshop, or a stylist. There were also non-human participants; a white noise machine and a card game called ‘Illuminati’ produced in 1983 that portrays different conspiracy theories.

**So how does the format of the exhibition connect to the structure of the book?

LH: The eponymous book is supposed to be a token that contains the multitude of worlds presented within the exhibition project. Nat relates to each and every object in his poetic text. This seems to occur in its own peculiar universe and works to connect the chapters. Each chapter then gives a voice to the exhibition participants through interviews.

Nat and I had a strong motivation to make the conversations between him and the participants dialogical, instead of being a question-answer process. His role was therefore heightened in that he’s a completely equal voice. The book was then designed by a graphic design studio, namely by Jan Broz with the help of Armands Freibergs, and its visual communication is essential. You can see the works in the installation — the object itself — and sometimes you just see macro photography of it, like a texture.

**What’s your relationship with nature? I noticed that you post lots of images of nature and organic patterns on Instagram.

LH: I’m extremely interested in patterns in nature. It has a lot to do with the physical superficiality of them and also with the straightforward depiction of a 3D space in 2D in photographic vision.

I don’t think this perception is something I was born with but through the technologization of everyday life, I have very much acquired a photographic vision, a CGI appreciation of nature. As humans, we definitely get a lot of pleasure from screens, right? For some reason, we are surrounded by 360 degrees of visual stimuli but we still stare at the screen. I feel that I’ve appropriated this way of vision that’s almost machine-like. I perceive the sort of, say, ‘androidization’ of the human, as well. I’m not saying that’s good or bad.

**You were recently awarded the Jindřich Chalupecký Award. As part of the four-month long exhibition you presented ‘Sospiri‘, which was both an installation and a two-hour performance piece. Is this your first installation work?

LH: To put it really simple, it is my first authorial artistic installation, yes. I would say that, within a performance, I use objectification as a strategy, either way. I’ve always been invested in how objects can become tokens of emotion. A method that’s widely used in performance, that I also stand by, is that the object is a relic of a performance, carrying its momentous historical value.

**Can you tell me about a few of the cultural references behind the work?

LH: I find a lot of mythology in popular culture. For instance, in action movies like Terminator, the main hero lifts up the injured or deceased person (likely a female) and carries them to safety. You encounter this motion in my performances. The one that’s been lifted giving their body as an object. It’s useful. Sometimes, there’s a lot of liberation in self-objectification. I don’t mean sexual objectification of women but rather just to let go of this weight, or burden of existence, of being human. It’s crude to say it but at the same time this brings a healing, redemptory effect.

Talking about things like CPR, absence of breathing, or the state of being moribund, etcetera. I feel that the ‘Sospiri’ performance is spent in a state of semi-life. Sospiri was this word that stuck with me, having watched lots of Peter Greenaway. It’s an operatic term; opera being this highly dramatic event that’s wildly choreographed and flamboyant. He also uses medieval or renaissance stylising, which I think you can see as an inspiration in my work.

In ‘Sospiri’, the performers start behind a membrane with the audience on the other side. The actants are pressing against the glass as if they were magnetized or forced to by a gravitational pull of some kind. But aggressively so, towards reality as if they’re in the Netherworld. It created a kind of twisted tableau vivant in which the three-dimensionality was pushed into its 2D representation only.

**It’s funny that we’ve talked so much about texture and pattern because I always get your moniker Saliva confused with the musician Ssaliva.

LH: I really like that guy. Of course, we know of each other’s existence through Instagram. Somehow we chose the same handles and that has become part of our identity or persona, right?

**In the sense that the identity, like the name, has been stretched like a fibre out into another reality…

LH: I feel about him sort of that way. Perhaps he does too. There was an event once when he was on the residency at a spot where I was co-organising a club night and we had him DJ on the same night as me. So you would have DJ Ssaliva and DJ Ssaalliivvaa. What a metaphysical mind fuck. Let’s tag him in a post on Instagram, I think it will confuse people further.**

Lukáš Hofmann’s A guiding dog for a blind dog was published on Prague’s Futura Books in February 2019