“Even if it’s called the anthropocene, we’re still not actually in control of anything,” says artist Alma Heikkilä, while sitting in front of her own paintings in Helsinki’s Kiasma museum for contemporary art. They’re part of her ornately titled ‘ , ‘ /~` mediums,.’_ ” bodies,.’_ ” ° ∞ logs,∞ ‘ , ‘ /~` ‘ holes, .’ `-. ` .’ — °habitats / /`‘ * ‘-‘ . ‘ , ‘ /~`want to feel (,) you inside \| * . . * * \| * . . *./. .-. ~ .’ ‘ , ‘ /~` ❅ ☼ ~ solo exhibition, running March 15 to July 28, with earthy-coloured canvases and jutting pastel growths resembling mushrooms. “We can never produce all the things we need in our life. We can’t produce our food, we need other plants and animals and living things to do that; to grow and to decay and to produce oxygen. So we are super dependent on other [species].”

Based in Helsinki, Heikkilä is a founding member of Mustarinda, a multidisciplinary collective located in the old-growth forests of northern Finland that hosts residencies and workshops at the intersection between art and ecology. The artist’s current exhibition at Kiasma will enter the museum’s permanent collection. In past painting and installation projects such as 2017’s None are truly separate, Heikkilä has often involved fungi, organic matter and an interest in microbial life forms, either applied directly onto the canvas or through representation.

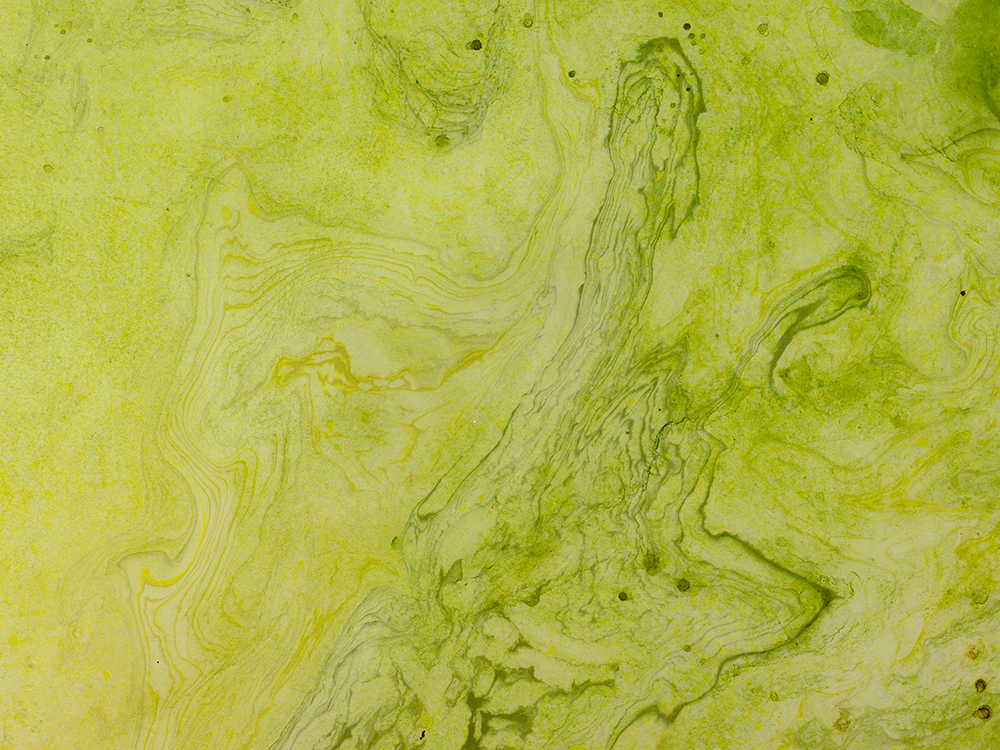

For ‘ , ‘ /~` mediums,.’_ ”…., Heikkilä takes painting—a loaded format elevated in the anthropocentric thinking of art history—and opens it up to the elements, working with the natural daylight of the space. The largest work on display is a single canvas stretched to fit the full length of the gallery’s window. Lit by a skylight and also from behind, Heikkilä relinquishes an element of human control from the show’s viewing conditions and places the work in a continual conversation with the weather and seasons. Paintings with titles like ‘warm and moist / decaying wood’ are accompanied by speculative lists of media evoking the inescapable presence of other species in the museum’s pristine environment: “red, gastrointestinal tract, vomit, nipples, Mycetophilidae, Fuligo septica slime molds, jelly fungus, mycelium, Parasitoid wasps,” etcetera. Heikkilä has enlisted dramaturge Elina Minn to conceive of movement activities for visitors as they spend time in the space, either through a set of written instructions or in workshops hosted by Minn, inviting a consciously embodied aspect to the viewing of her paintings.

The city of Helsinki is still powdered in its usual mid-March snow. It’s a comforting bit of climate normality after an oddly early spring in other parts of Europe. A couple weeks earlier in London, it was the warmest February ever recorded in the UK. The mercury peaked at 21 degrees celsius ironically in Kew Gardens, a Victorian botanical garden full of glasshouses emblematic of an empire’s attempt at capturing and controlling nature. This mood of seasons out of step makes fertile ground for discussion with Heikkilä, whose practice is centred on multispecies thinking, the anthropocene and how we might live with nature into the uncertain future.

** I’d like to talk about your interest in fungi. I recently learnt that The New York Mycological Society was founded by John Cage. I’m wondering if there’s a cross-pollination or history of artists having a particular interest in fungi, or maybe it’s just one big coincidence?

Alma Heikkilä: Beatrix Potter used to draw a lot of fungi, these amazingly beautiful images. I think, earlier in history, you can see very detailed images of different species, for example in painting. But in general the research of fungi has focused mainly on mammals and of course a lot on human bodies, and less and less on fungi and different fungi that are hard to reach. It’s maybe more difficult to relate. That’s kind of interesting for artists because there’s a lot of space for imagination and for something that is unknown. In Finland, it features a lot in folklore because fungi have always been used for medicine and there’s this long history of different kinds of encounters.

** In popular discussion on news and social media, there seems to be this recurring theme where people talk about the world not really making sense anymore—particularly our human-centered view of the world—whether through politics, or what technology has done with us, or climate change. What are your thoughts on that in relation to your practice?

AK: Well, personally I always go back to basics. Like here I’ve been thinking of exactly that: whatever we think and do we always need the other species to survive. Maureen O’Malley says that this is the ‘age of bacteria’, in the sense that we are still mostly dependent on these other species in every activity that we have.

Even if it’s very difficult to make decisions and know the best way to proceed, there are always some that are really easy and some that you can decide are for better or for worse.

It’s more difficult to do anything good or to know exactly what that is but I think we all know a lot of things that we can do differently. Maybe in art it’s about giving the space and time to feel differently, and to talk about, not the solutions or things that you find important, but the insecurities, struggles and mixed feelings.

** I’m interested in this ‘age of bacteria’, can you tell me about it?

AK: There is a text [on this topic] by Scott Gilbert in the catalogue, he’s one of the authors I’ve been interested in and I’m super happy he wrote it. This idea that the majority of living things—as a weight, as a number, as in any measure—are microbial life forms. In animals and plants there are microbes. They also live several kilometres inside the earth and in super harsh environments. If you think of evolution, they’ve taken part in every step and still are the main kind of ‘life keepers’, you could say.

** I’m interested in the growing awareness of things like gut bacteria and how we think of ourselves…

AK: Yeah, exactly. This idea of individuality, I find super interesting in many ways.

Scott Gilbert has this one text on biological individuality, where he puts forward that in many senses it doesn’t exist. But also in human culture, ideas of individuality, of being separate from others and these sort of things, are very intriguing and also something that I struggle with. Maybe in the end I always feel very individual and very separate, even though I am trying to feel differently or to go other directions but it’s not so straightforward. And, of course, not all symbiotic life is good or good for us.

** I was reading recently about oyster mushrooms and their ability to be used on oil spills; to absorb the toxins or digest them. With these proposed solutions to waste, does the mushroom then become just another material resource?

AK: There’s so much that we don’t know but I think it’s quite evident and clear that things need to be consumed less. Research around fungi is very hot, also research into the soil as a carbon sink. And of course that there are other species, bacteria and things that can live in hostile environments, and somehow clean the environment. I’ve been thinking that human bodies could be and are already, in a way, cleaning the environment. We are collecting a lot of the pollution [laughs], which is of course something that we don’t want to happen but it’s the same method, when we die we are really like a sink.

**I’m quite interested in your want to use natural light in this installation, and also with Elina Minn’s dramaturgy. It sounds like you’ve really considered the embodied experience of visitors in the space and how no two visits are really going to be the same. It got me thinking about how we actually encounter exhibitions so much through the digital distribution of the documentation nowadays. I wondered if you had any thoughts on that in relation to your show?

AK: Earlier in my work, I’ve been getting all sorts of knowledge from looking at screens. Basically, all of my research has been done by looking at screens. I think there’s something really nice in painting as a technique, that it makes people spend a little more time on something. I guess, if you see that it takes time to do it, then you appreciate it more. I hope there will be more time to feel. That’s what I’m interested in personally. There’s so much knowledge at the moment, if you think of the environmental crisis. Basically, everyone knows. It’s more like you don’t have time to digest it, to feel. Of course, I would love if people would spend time here and I’m really interested in what Elina will do, and also what she’s done before, but then there’s little that I can really affect.

** I’m wondering about the life of the show. Are there organic processes—or does it evolve, does grow mould [laughs]?

AK: No, there should not be. Of course, there’s always something in every artwork. There’s no vacuum over the whole planet but the works are very well taken care of by the conservation team [laughs].

** It’s an interesting irony, isn’t it?

AK: Exactly. In the very beginning, we discussed the boundaries of how the works will be a part of the collection and also shown in this space, which is quite different from other exhibition spaces as it’s very high and has a window. Also, the size and type of material has to be something that they can transport. Museums are very much still in this mode; that everything will last for the next 150 years easily or 1000 years—which is something I’ve been trying to evoke discussion around. At the moment, if you think about what the future is expected to be 30 years from now, it is a big challenge for the democratic state, for example, and also for culture, and the cultural institutions and even art storages. So they are not really going hand in hand, the methods that the art institutions are working with and the future that they are heading towards.**

Alma Heikkilä’s ‘ , ‘ /~` mediums,.’_ ” bodies,.’_ ” ° ∞ logs,∞ ‘ , ‘ /~` ‘ holes, .’ `-. ` .’ — °habitats / /` ‘ * ‘-‘ . ‘ , ‘ /~`want to feel (,) you inside \| * . . * * \| * . . *./. .-. ~ .’ ‘ , ‘ /~` ❅ ☼ ~ solo exhibition is on at Helsinki’s Kiasma, running March 15 to July 28, 2019.