Gathering together 18 artists from 9 nationalities, the inaugural Strasbourg Biennale — running December 22 to March 3 — places a timely consideration of digital globalisation, local politics and the state of the EU today. Following a similar format to the now hundreds of biennales worldwide, the main exhibition presented in the UNESCO-protected Hôtel des Postes is supported by smaller sites throughout the city, and through a live programme of talks, workshops and gigs.

Established by local curator Yasmina Khouaidjia, the intent of the Touch Me – Being a Citizen in the Digital Age theme is to explore “the nature of human responsibilities in a rapidly changing world”, while inviting local audiences to ‘relate’. From the outset, Khouaidjia proclaims that the ‘digital’ will in fact be the enduring theme of subsequent editions of the biennale, but sets this remit apart from a slew of existing media arts festivals by placing an emphasis squarely on the agency of the citizen. The wider concerns of ‘The State’ and forms of governance implicit in this curatorial direction are reinforced by the border city’s profile as the so-called “cradle of German humanism” and as one of three capitals of the European Union.

As an attempt at mapping how we interact with contemporary modes of economic, political and social power, Touch Me looks to examine the way in which these relationships operate today on a distinctly biopolitical level. In an emergent landscape, individual works explore the interactions where we at once use and are used, where we are subsequently controlled and our value abstracted. Evan Roth’s ‘Next, Next, Next’ (2014) details addictive scrolling behaviours in smartphone use while Constant Dullaart’s ‘The Fleur De Lis’ (2017) series explores how beliefs and opinions can be manipulated at an increasingly granular level through the creation and deployment of an army of fake social media accounts. The programme asks us how aware or submitting we are to this dynamic, but stops short at developing a cohesive argument for change or opening up a conversation around methods of resistance.

Like many cities across Europe, Strasbourg is celebrated for its art and architecture; the Cathédrale Notre Dame de Strasbourg, the Palais du Rhin, the Palais Rohan — all clear representations of power held by church and state through the ages. Against this historical identity, Touch Me begins to draw out how those who look to govern have moved away from securing confidence with their citizens (or consumers) through such ornate brick and mortar institutions towards a ubiquitous, intelligence-led process. One facilitated by a vast technological infrastructure and centred on profiling as well as predicting behaviour.

Trevor Paglen’s work reflects on how we too often fall into the trap of conceptualising the digital as ethereal, rhizomatic and therefore beyond individual reach. The geographer, artist and author has dedicated his life to revealing the shifting topology of mass surveillance and data collection. In his photographic print work ‘NSA-Tapped Fiber Optic Cable Landing Site, Mastic Beach, New York, United States’ (2015) a popular beachfront sits atop an important landing point for several transatlantic submarine fibre optic cables that — as discovered from documents in the Snowden archive — the NSA have tapped. Lazy in the summer heat, the image is really only eerie once you become aware of why the site is significant.

Governance and legislation surfaces throughout the programme as both a positive and negative driver of change. In Jia’s ‘The Chinese Version’ (2014), hand painted canvases present the written characters for sentiments such as profound happiness that are now ‘lost’, removed from the alphabet during the ‘cultural atrocity’ of the Chinese simplification programme. Initiated for the purpose of propagandistic ends in the 1950s, the policy remains in force today in the People’s Republic of China. Alienated from their original meanings, these formal illustrations silently stand in for the volumes of academic writing, literature and art that has become illegible and therefore inaccessible to today’s generation.

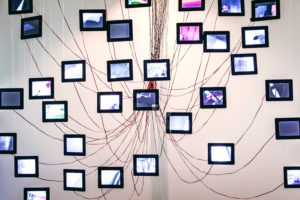

“Privacy is a human right, it is not a given and therefore it needs to be protected a fought for,” says artist Florian Mehnert as he discusses his installation ‘MENSCHENTRACKS’ (2014) during a guided tour of the exhibition. In front of us, displayed on 42 tablet-sized screens, are video clips recorded from the hacked mobile phones of strangers who unwittingly provided access to their camera roll in return for free WiFi. There are no great poetic insights in the bumpy footage. Someone is in the toilet, another walking in a park, phones travel in pockets or hands. However, it is the the general public’s apathetic reaction to the invasion of privacy that could be seen as disturbing. The artist observes that when confronted with the work, people too often fall back on the dangerous adage that, if you’ve got nothing to hide, you’ve got nothing to fear.

Other works in the show continue to open up a conversation around privacy and ownership that reinforce Mehnert’s opinion that policymakers are not moving quickly enough to draw sufficient boundaries and combat exploitation. This is due perhaps to a lack of popular alarm, but also because events are happening too fast for legislative bodies to adequately respond. In Constant Dullaart’s ‘Terms of Service’ (2014), an anthropomorphised search bar reads the purposely opaque and continuously changing list of conditions that users are required to submit to, making a rather simple but impactful gesture.

Paolo Cirio prints out images of people captured in Google Street View for his work ‘Street Ghosts’ (2012) and pastes life-sized copies onto walls throughout Strasbourg, at the precise spots where they originally appeared. Here, the artist appropriates the image to highlight the way in which Google acts not with the direct permission of the individual as would be expected but instead does so in negotiation with local governments.

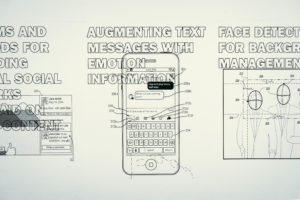

Cirio’s most recent work, ‘Sociality’ (2018) takes an important step beyond simply highlighting our fate towards proactive collaborative change. The project is first and foremost a database of over 20,000 patents for “online platforms, interfaces, algorithms, and devices” submitted to offices worldwide. Looking around the room at printed examples, it is clear how in our now seamlessly digitised culture, a string of these patents can be licensed into one product in such a way that a single experience can be precisely broken apart and monetised by multiple agents simultaneously. With both startups and larger tech agencies producing countless unchecked ‘solutions’, through ‘Sociality’ Cirio advocates for greater accountability and regulation in the design of digital interfaces and algorithmic data mining. The artist invites users to scrutinise each patent and then either ‘ban’ or ‘flag’ it, slowly building up a public response which Cirio then forwards on to legislators, academics, activists and journalists to use in their campaigning.

Testing the boundaries of the relationship between user and provider is Mark Farid. The London-based artist’s extreme presentations of the self that explore “individual privacy and its metamorphosis in contemporary society through technology,” Farid’s work is often the outcome of a longer social experiment in which he subjects himself to arduous and risky situations. In ‘Data Shadow’ (2015), he created an open document listing each one of his logins, which — playing into our common fears — concluded in someone committing fraud against him and a decimated credit rating. Having given away one digital identity, he then attempted over the next 6 months to evade creating another, using only cash, pay-as-you-go phones, IP spoofing and firewalls. Through this process, he found that “as a 23/24 year old living in London, there is no real choice” as to whether or not to use these modes of communication as (perhaps contrary to opinion) the digital detox had left him feeling increasingly isolated and depressed. For his film ‘Poisonous Antidote’ (2016) made in collaboration with Sophie le Roux, Farid returned to his established user behaviour and in doing so broadcast his digital footprint for 31 days: emails, messages, phone calls, Skype, tagged photos, locations, web browsing, apps and even music. In doing so the artist provides the embodied experience at the other end of big data capture, mapping out tangible points during which identity is formed and conditioned in the endless feedback loop of new communications.

In this first edition of the Strasbourg Biennale, there is an identity starting to form that is specific to the city; how the Biennale engages with this sense of locality will be the most interesting aspect to watch in future editions. As a visitor it seemed unclear how the international conversation being brought to the table by a specific milieu of artists is meeting more concretely with local knowledge and expertise beyond the main exhibition. Within that, the list of invited participants could have benefitted from a broader cross-section of identities as the sample group exploring notions of citizenship, which in itself is a slippery term.

On leaving the city and the biennale, the yellow-vested Gilets jaunes stood idly by during their weekly protest, lighting bonfires and eventually coming together in a more cohesive march through the city centre. This spontaneous movement of civil dissatisfaction at life under neoliberal austerity signals a need for curtailing the corrosive influence of stateless for-profit firms on the social body. Platforms such as Touch Me echo this and could grow to provide an ongoing space in which to foster awareness and discussion. Going back to the original proposition of the event, our responsibility as citizens is therefore to connect the dots between the financialisation of everyday life, with the technologies, laws and relationships that enable it. The continuing presence of the Gilets jaunes across French cities — itself the result of galvanised sentiment on social media platforms — shows that the ‘digital’ is a lot more tangible than we think.**