“By showing my mistakes, I hope to reveal somehow the ridiculousness of K-Pop” writes Soohyun Choi when I ask about her recent performance video, ‘I’m Like TT, Just Like TT’ (2017). “But rather than pointing out what the problems are, I wanted to fool myself into playing the part and see what happens”. In the piece, the London-based artist is accompanied by two friends, both aspiring celebrities she met through K-Pop fan bases. We watch as she attempts to clumsily learn the dance choreography to a hit song and eventually record her own fan video. Suspending a circumscriptive judgement of K-Pop’s obsession with celebrity status in favour of entering into the image.

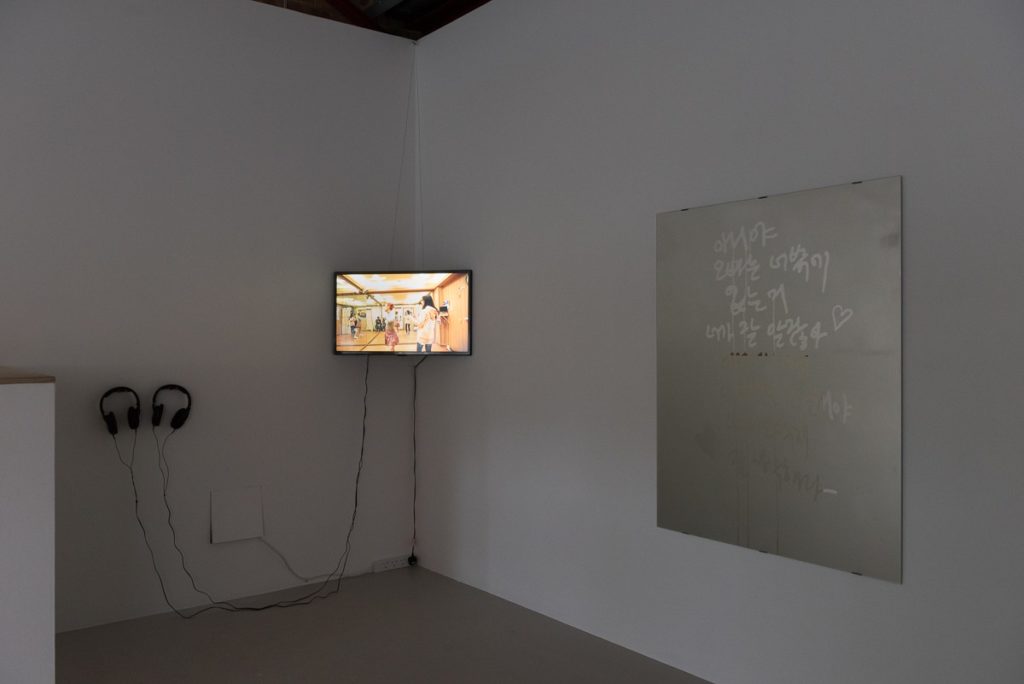

This is a common approach of the Seoul-born Choi, to find other ways of knowing and relating more intimately to familiar situations — such as teenage pop crazes, romantic love or even filmic tropes — ones that we often come to with readymade assumptions. In previous works such as ‘My Love’ (2015) the artist exhibits these intimate relations first hand, listing lover’s nicknames in a way that suggests a kind of coercive ownership. Or in ‘You know that all I have is you, if you leave, now this is the end’ (2017) love notes are written in Korean on steamed bathroom mirrors. Here, a productive gap between languages transforms untranslated Korean text into a kind of opaque image of transition.

The movement of this staging of intimacy, from interior to exterior, is then reversed by Choi in ‘Snow Romance’ (2016). In the video piece, the artist deconstructs the seductive image of filmic representation — in this case the ‘snow scene’ from the Edward Scissorhands. Presenting it as a durational performance, it is stretched out through the use of cinematic framing to the point of unravelling. We see the artist enter into the image in an effort to know it closer, as a kind of deconstruction from the inside.

Meeting in London’s Victoria Park, Choi took the time to chat about her most recent work ‘Pool Memory’ (2018), expanding on the conversation over email since. The piece — which was one of five works installed in the show Hypnogogic Holiday at Peckham’s Safehouse 2 from June 7 to 9 — was filmed with a GoPro attached to the artist while swimming in a hotel pool. Made at a time when she felt the need to escape and find some space. The camera passes through the underwater and overwater area of the pool with each stroke. The subaquatic footage explores the material qualities of the submerged body; the sound, its liquid rhythms, its flowing sense of timelessness and weightlessness. The moving image above water reveals the architectural interior of the leisure centre, intercut with fragments from the surrounding urban environment, skyscrapers and tourist crowds and a mysterious figure sat looking into the distance. In a shift from previous works, Choi uses editing to establish a divergent tone, oscillating between claustrophilia (a love of enclosed spaces) and claustrophobia (a fear). The desire for a sensuous, immediate and playful absorption of the body in water and the uncanny apprehension of a more implicit type of horrific immersion. Below, Choi discusses how she navigates these various states of anxiety, desire and awkwardness in her work in an effort to find alternative ways of relating.

**Could you tell us a bit about your most recent work ‘Pool Memory’ (2018) and how you came to make it?

Soohyun Choi: The idea for this work came when I was travelling with my family in Chicago. It was a special trip for us as we barely get to see each other and we stayed in a luxurious five-star hotel in the west side of the city. It is a cliché to say but it felt like walking onto a film set. We know aspects of American life in such a mediated way, yet when you encounter the real version, these clichés feel really strange.

All the work roles felt very subservient and the hotel structure felt very openly imperial, even though it tried to present itself as a space of leisure and escape. It felt like a constant realisation of imperial capitalism. All these things are so constructed but how can you use these spaces? I don’t want to be misunderstood as giving out about staying in a fancy hotel but it was a strange experience. I couldn’t feel comfortable or think of it as enjoyable. And yet there was this desire for comfort. I thought going for a swim would be the most escapist thing I could do. So I went down to the pool and made some footage with the GoPro I had and this became the beginning of the work.

**I was wondering about the connections between the type of leisure space you experienced on your holiday and the post-production space of editing, or even the reflective spaces of art more generally as somewhat privileged spaces of viewing?

SC: A holiday is itself an escape but it feels it is never really possible, like a daydream that somehow transports you to another space but is still materially bound or produced. The line between leisure and work seems blurry and really not easy to distinguish as we live in a time when the idea of work never ends. Or, if I am on holiday, I’m under pressure to enjoy the moment. I am nowhere, in between those work and leisure states. Contemporary modes of work have trapped us and we have forgotten how to have fun or enjoy ourselves without the structure of a holiday. But even if on holiday, we work constantly and in the meantime, we try to prove that we are having fun.

**In previous works you have deployed staged scenarios where the outcome is already quite determined. In ‘Once we went to see the cherry blossom’ (2016) you read from a script in front of a projected animation of cherry blossom petals. In ‘I’m TT, Just Like TT’ (2017) you filmed yourself rehearsing for a K-Pop fan video. However, your approach to ‘Pool Memory’ seems a lot less overdetermined and much closer to a kind of explorative documentary-style. What lead you to take this approach?

SC: I was wondering if I could communicate a sense of anxiety or alienation without words or an explicit narrative; more indirectly, through sound or an atmosphere or a feeling. I thought there’s some kind of narrative but nothing really specific or scripted. There’s just the simple scene of the swimming pool. In this setting, I wanted to see how I could construct the feeling out of the video material itself, rather than building up a staged performance of one specific situation.

**Previous to ‘Pool Memory’, you also used documentary techniques in the making of ‘Balls and Balloons’ (2017). It shows both an awkwardness towards, yet also a desire to engage with some of the power dynamics at play in the encounter with this young person who was earning money busking. Could you tell us a bit more about your encounter with the juggler?

SC: I was doing a residency in Athens and there was this boy juggling most of the days on the street where I was staying. I was interested in how his hobby became a means to earn money and myself being there working as an artist. I started writing a text around this juggler as a piece to perform but I thought this approach would be exploitative, imposing an outsider point of view. So I decided to go and talk to him and the video is the edited outcome of that conversation. There are many things happening in the video — my feelings of shame or guilt for taking his time, the boy helping me to make an artwork, the awkward moment in the shop when they didn’t have a change for my 50 euro note, the conversation around ethics and money, etc.

**In your video ‘Snow Romance’ (2016), you staged a kind of durational performance based on a scene from Tim Burton’s 1990 film Edward Scissorhands where a snow machine covers you with artificial snow. Any kind of dominant narrative seems to unravel through its durational quality, a bit like how comedy can excavate multiple meanings of a phrase or saying over time. How did you decide on that structure for the work?

SC: The work started from two interests: one was how we are influenced by a representation of a seductive image in films and the second was an attempt to make a video based on the documentation of a performance, into a mimic of a film or using a kind of cinematic set up; a sort of Brechtian approach. It first struck me when I watched the famous snow scene from Edward Scissorhands that it is a beautiful scene but it implies many layers of camera shooting, gaze and stereotypes of romance. By performing in front of the camera, I was trying to place myself in the position of the girl in the film, wanting to be part of seductive image, in order to begin to understand it in more intimate way, not simply just consuming it.

**A lot of your previous work, such as ‘Girl in the shower’ (2015), ‘The shape of the Heart’ (2018) and ‘My Love’ (2015) draw on quite intimate moments and spaces; bathrooms, showers, notes from lovers. Do you draw on these moments as they happen, almost seeking them out as source material, or are they things that stay with you over time, which you then develop or respond to?

SC: Those scenes or images come mostly from seeing myself as a person with various identities, such as being a female, Korean, artist and daughter and many others. Those identities are structured from many years of manipulation by various media, social stereotypes and constraints. Heterosexual relationships are one of the most clichéd and obliged social constraints constantly presented in media. I’m interested in what the feeling that relates to the notion of love is, even if you try to understand it as an ideology. I was trying to deliver the feeling of the moment by using tools like lovers nicknames or romantic moments such as drawing a heart on the bathroom mirror. They contain some of the complexity or inseparable states of rationality and feeling, which change from romantic into something creepy so easily.

**You mentioned in a previous interview how you thought language was a core structure of the Self. For your mirror paintings, such as ‘You know that all I have is you, if you leave me now it is the end’ (2017), you worked more explicitly with language, producing a Korean text that looks like it had been drawn by a finger into the condensation on the surface of a mirror, yet you chose to give that an English title. How do you relate to the gap between two languages, do you find the movement from one language to another to be productive?

SC: This in-between state in languages is fricative and comes with not knowing, with mistakes and mistranslations. Sometimes I have to switch between languages to articulate myself and sometimes certain parts of me are expressed better in one language and not the other. I am curious of the possibility of translation and its limit and the possibilities that can occur from this limit.

With ‘You know that all I have is you…’, I was thinking about the relationship between word and image. The hand-written text on the mirror is an attempt to write but also to draw at the same time. If you don’t know how to read the language, the text becomes an image. This process of translating into a language that you don’t know completely relies on the translator’s understanding of the text and their knowledge of that language. I enjoy the process that happens through not knowing and the ‘re-re-translation’ and transliteration, which is always happening.

With the mirror series, the literal translation of what I have written or drawn on the mirror into English was not so easy or straightforward. Even though I can speak English fairly well, the exact delivery of the meaning is not really possible. But I like that the language becomes an image and the English title becomes a title of the work itself that’s not particularly indicating the exact translation of what it is written. People have asked me how I would present this work in Korea. I decided recently that its title would stay in English and not be re-translated into Korean. It only has one title (in English) and there’s always going to be that gap there.

**I’m interested in this idea of locating artworks and their circulation. It relates to that opaque aspect of translation in language. I was wondering about ‘I’m Like TT, Just Like TT’ (2017), where you filmed yourself and some other performers rehearsing a K-Pop song routine. It seemed to be a way of exploring the genre from within itself; making a video that could re-circulate amongst the networks of fans. Can you describe how you made the work and the maybe where the title comes from?

SC: ‘TT’ was a hit song for the band Twice in 2016. It started when I realised that there are so many cover videos by their fans on Youtube and I thought I could make a version of a fan video by adopting some of the aesthetics used in these videos. My reason for picking this song is that I felt ‘TT’ represented the infantilised condition of some Korean girls very well. The lyrics translate roughly as “I am in the condition of TT because you don’t love me” and “I am crying, passive, cute, so why don’t you love me?” And TT is the emoticon for crying, which is again, the language is transferred to read as image.

I filmed the video with two friends in a small practicing room in Seoul. In my video, the set-up was very amateuristic and there are many tacky zooms. My friends are genuinely trying hard to teach me and I’m terrible at dancing. By showing my mistakes, I hoped to reveal somehow the ridiculousness of K-Pop and the many problems around it. But rather than pointing out what the problems are, I wanted to fool myself into playing the part and see what happens.

K-pop presents the desire to be recognised and be loved through a particular form, which is to become an idol. The difference between a pop idol and a musician is that a musician will make the music of their choice but becoming an idol is following systematically-produced music and choreography without a choice. To be an idol is one of the jobs that most teenagers want. But with any ambition to be a celebrity and the endless circulation of familiar forms of music and images, you begin to wonder, how many idols can we have? How much can we reproduce this?**

The Hypnogogic Holiday group exhibition was on at London’s Safehouse 2, which ran June 8 to 9, 2018.