“Let’s say I have had a personal awakening with regard to class, and race, and cultural dominance within the UK music and arts,” writes East Man (aka Anthoney Hart) in an email about his developments and disappointments as an artist and producer. Starting out in the the drum ‘n’ bass and pirate radio scene of the 90s before moving to the post-apocalyptic dystopias of J. G. Ballard‘s books and the hifalutin noise of experimental electronica in the 00s, Hart’s experience of the British capital is uniquely concentrated on the peripheries of East London and Essex. His family is from Bow and he’s lived between his birthplace of Hastings, on the south coast of England, and London before finally settling in the capital city; from then on moving frequently between districts — Ilford, Forest Gate, Woodford, Barkingside, Hainault, Romford.

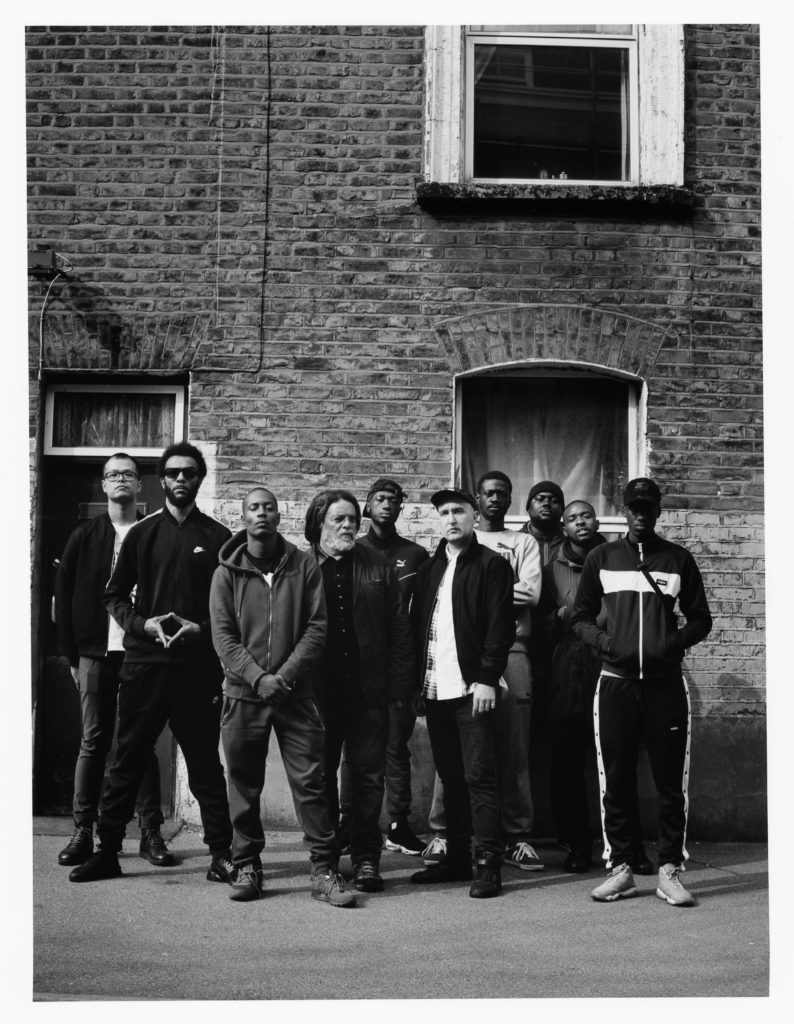

Parallel to all the movement, Hart has always been making music, searching for a sound through a number of projects before finally coalescing in an approach that incorporates DnB, dancehall, techno, noise and grime in a style that he calls ‘Hi Tek.’ The outcome is the Red, White & Zero album, out now via London’s Planet Mu and featuring vocals from a number of emcees from around the city — Killa P, Irah, Saint P, Lyrical Strally, Darkos Strife, Kwam, and Eklipse. Here, samples of old pirate radio shows and an excerpt from 80s documentary film We Were the Lambeth Boys is met with the sharply textured edges of beats that embrace and contort with its local influences; of an imperfect though vital youth culture on the margins of society that eminent scholar Paul Gilroy describes in the album’s in-sleeve text: “They hustle, they suffer, and they survive.”

In honour of this past and in support of its continuation into the present, Hart shares a mix of influences and unreleased tracks via AQNB, along with some thoughts on the state of music in the age of austerity and his disillusionment with life on the losing side of a class war.

**You’ve had a rather unique experience with a number of scenes through your life. Can you tell me something about that experience and what you’ve learned along the way?

Anthoney Hart: When I first started out as a DJ under a different name back in the 90s, it was a very different scene, and the goals were simpler. You wanted to play on pirate radio, put out some 12-inches and play at raves like Telepathy or One Nation. It wasn’t as lovely and rose-tinted as some like to paint it now, there were a lot of clashes and rivalries, and some violence too, but there was an honesty to it. You had space, as a working class person, to create and express yourself freely, and even earn some money from it.

AH: I feel completely disillusioned and frustrated with the contemporary art and music scene in the UK, and Europe to an extent, at the moment. There are many reasons why, but I will focus on the main issues directly, in my mind, to do with the impact of the financial crisis and the dominance of the arts. The way I see it, since the financial crisis and the ‘age of austerity,’ money has been scarce, funding even more so, and you have had a creeping dominance of certain sectors of society, which have now reached the point of it feeling like a monoculture.

The impact that the arts has had on the music world over the past few years is palpable right now. As there are fewer and fewer sources of funding, and finances are tighter and tighter for those at the bottom rungs of society, the ability to take a risk creatively is narrowing daily, and the only sources of funding are held by the arts sector. You end up having to appeal to a monoculture and whatever it has decided to fetishise or co-opt this month. This leaves scant room for anyone operating outside of that that isn’t on trend for a white, middle class audience. This is also evident in the bookings you get, either arts festivals or clubs, the people booking you are all the same, and the audiences you are playing to are all the same. And finding a way to navigate this and connect with it is becoming an increasingly hard challenge for me and many others I speak to. This isn’t even touching upon the impact of corporate sponsorship on the music scene but, in my mind, the effects are largely the same.

**I remember walking through Stratford Station with you one night and you telling me how much the area had changed since you were a teenager; the raves you went to that were both dangerous and vital, to a degree, are unmatched by what we know as raves today. You spoke as if they had vanished and it’s a feeling Gilroy echoes in his accompanying in-sleeve text, where he says the space for youthful creativity has contracted in favour of property development. Is this a sentiment you share?

AH: The Stratford Rex days, ha! Yes, I think it is part and parcel of what I was just talking about: The city as a zone of exclusion for those of us who aren’t of a certain background, or don’t have the things to give that are wanted and expected from us at any given time. You only have to look at Grenfell and what has happened since, to get a picture of how London operates today, and this is mirrored in what we see being given space within music and the arts, and the voices we see being squashed and marginalised even further.**