The idea that you could use a Shepard-Risset glissando to get “Fortified Up,” as the last track on Lucy Railton’s debut album Paradise 94 suggests, is compelling. The auditory effect is produced through the implementation of a psychoacoustic technique patterned to create the sensation of a swarm of frequencies endlessly ascending or descending in pitch, like an Escher drawing. It can go on forever. Depending on how it is performed, the glissando can be relatively smooth (with notes curving and fading out in balanced, synchronized distribution) or a little bit more unevenly striated. “Fortified Up” is recorded binaurally, and performed by hand on cello — the instrument plays a major part on this album, which was released by Modern Love on March 23 — enabling a flexible wavering back and forth between these two poles.

Railton’s 11-minute composition creates a sense of funhouse destabilization, mixing anxiety and weightless euphoria. The feeling is a little bit like moving and staying in the same place simultaneously, while multiple images of yourself tear off and scatter in a blurry palimpsest—it’s queasy, strange, a little bit thrilling. The piece is the only one on the record that features the instrument without accompaniment by electronics or extensive studio editing in electroacoustic style. It is often said that the cello is the acoustic instrument that most resembles the human voice; on this track and on Paradise 94 as a whole, Railton manipulates this resonant dimension of anthropomorphized “natural-ness” as if it were an open-source template.

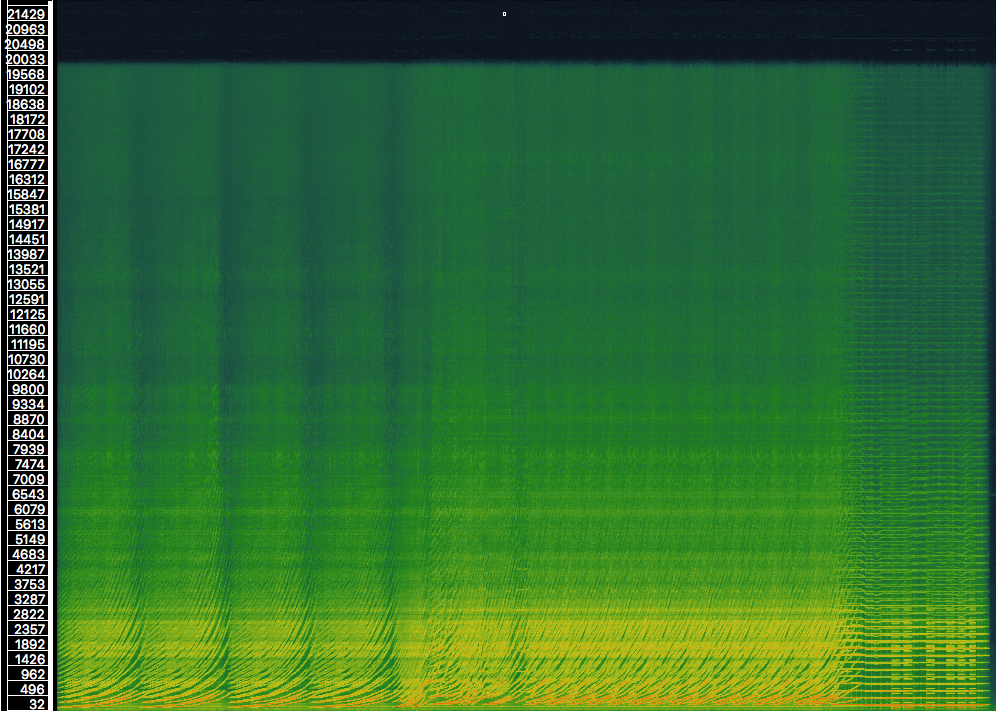

“Fortified Up” is composed in three sections, which results in a visually compelling triptych when plugged into a spectrogram (see accompanying image). The first consists of several iterations of the aforementioned glissando effect glued together by gaps of silence: in each instance, it perilously gains steam, reaches equilibrium and a sense of self-propulsion, and then disbands. After a brief pause, it begins again, cycling four times in total. In the piece’s second section, the impression of infinite ascent is sustained for several minutes, during which it is throttled in intensity, tone, and emotional tenor. Accelerating, decelerating, gliding up and down in general frequency zone—it materializes not as a note or a chord but as a time-stretched blur, vaporous and dispersed.

The final section of the piece is a sustained drone, featuring a higher note that lightly wobbles in pitch, occasionally joined in fraught harmony by its double an octave below. It takes years of practice to be able to effortlessly play the cello in strict, traditional Western intonation, as the instrument doesn’t have riffs like a guitar. Railton sets aside this hard-earned skill, choosing instead to explore beguiling, minutely wavering harmonies consisting of microtonal resonances and dissonances. The clouds part, and dopamine surges to simulate relief. On the spectrogram, the frequency formation looks like a symmetrically patterned textile, precisely designed; the wavelike series of superimposed curves from the previous section have become lines, compelled to sit a little more still. Fortified up.

Paradise 94 processes a heterogeneous range of enactments of musical duration: fast time, slow time, and lots in-between all get criss-crossed. The album as a format functions as an unevenly porous sieve for this compositional process, so that certain sounds are given more affordance than others according to a compellingly volatile agenda—one gets the sense of competing voices trying to gain control of a narrative. Moving from a synth processed to evoke muscular twisting (“To The End”), to elements of RnB (“The Critical Rush”) and devotional organ compositions (“Pinnevik,” “For JR”), each component sound-grouping on the record digests, moves through, and disposes of time at a strikingly unique rate. Railton is not at all hesitant to make stark left turns seemingly out of nowhere, and single songs often sound like several discrete compositions stitched together in an act of fervent improvisation, to great effect. A series of horizons bump up against one another, and the frame becomes crowded—inside begins to look like outside, and they blend. The result diverges stylistically from traditionalist formalizations of “chaos” in electroacoustic music, and feels highly personal. It is a treat to hear pages ripped out of the book as you’re reading it, a feeling not unlike the overcoming of repression thought too ossified to budge.

One downside to describing music with visual language is the risk of constricting sound to a three-dimensional conception of space premised on linearity and a certain sense of cohesion, which Paradise 94 ultimately exceeds. To use a phrase of composer and artist Maryanne Amacher’s, these are not “notes without ears.” Because Railton pays such attention to the nuances of their co-present unfolding, the various intersections and divergences of the album’s sounds in relation to the digital audio workstation’s universal grid are highlighted instead of denatured. The result is often thrilling, suggesting a genuinely unique approach to montage. “Gaslighter” thrives in this framework, stacking and crosshatching several variations on churning: sawed cello calving like a glacier, the rumble of a tireless machine, and tornado-synth, thick as thieves. It makes sense that the composer has previously collaborated with noise musician Russell Haswell. Charged field recordings, frantically nimble performances on acoustic instruments, and kinetic studio manipulations intermingle on the album’s generalized plane, filtered together by a cut-and-paste approach most defined by dual motions of durational persistence—sounds open and close without being hurried along—and stealth derailment.

Sharp, crystal-clear melodies evoking bent air wrench and swerve throughout, giving the record an overtly expressive character, mixing catharsis with dischord. It is important that this album ends with “Fortified Up,” which is stylistically very different and more than twice as long as any other track on the LP. It arrives at a perpendicular angle to the rest of Paradise 94, retrospectively adding a shaky a sense of grounding to its more quickly-paced, fragmented postulation. We get the sense that it could be a gesture considering the possibility of its own dissimulation. Thinking in terms of the album’s title, ‘Paradise’ is an emotionally loaded word, evoking imagery of a “temporary autonomous zone” in gleeful revolt. Yet its meaning on this album is not given specific dimensions or any substantial context clues. Paradise is undecided, and not necessarily resonant in any literal way.**

Lucy Railton’s Paradise 94 was released via Manchester’s Modern Love on March 23, 2018.