“I spent a year in University of California San Diego, doing research for my PhD, and I went to this technology research centre called Calit2. When I met the director he just said, ‘Welcome to the future.’” Zach Blas pauses for effect. I stare at him, waiting. “Yes, he was being completely sincere.” Speaking in a cafe close to Goldsmiths college in London where he teaches in the Visual Cultures department, the artist and writer tells me about the ideas he’s currently been exploring. His first major exhibition Contra-Internet is a stance against the hegemonic form of the post-Dotcom bubble internet, and an exploration of what makes techies tick. As current debate surrounding net neutrality in the United States rages on, Blas’ exhibition feels more urgent than ever.

Running at London’s Gasworks from September 21 to December 10, the show featured new commissions along with a couple of his previous video works, revolving around the singular theme of Contra-Internet. The artist and writer has spent much of his career researching and creating artworks that grapple with science, technology, and digital media through the theoretical frameworks of queer and feminist politics. Blas is friendly, and open to talking about his practice at length. More than an interview, it feels like a gossip session with a friend as we speculate on Silicon Valley entrepreneurs investing heavily in so-called ‘transhumanist’ technology, and whether the American economist and devout follower of Ayn Rand, Alan Greenspan, could have taken LSD in the 50s.

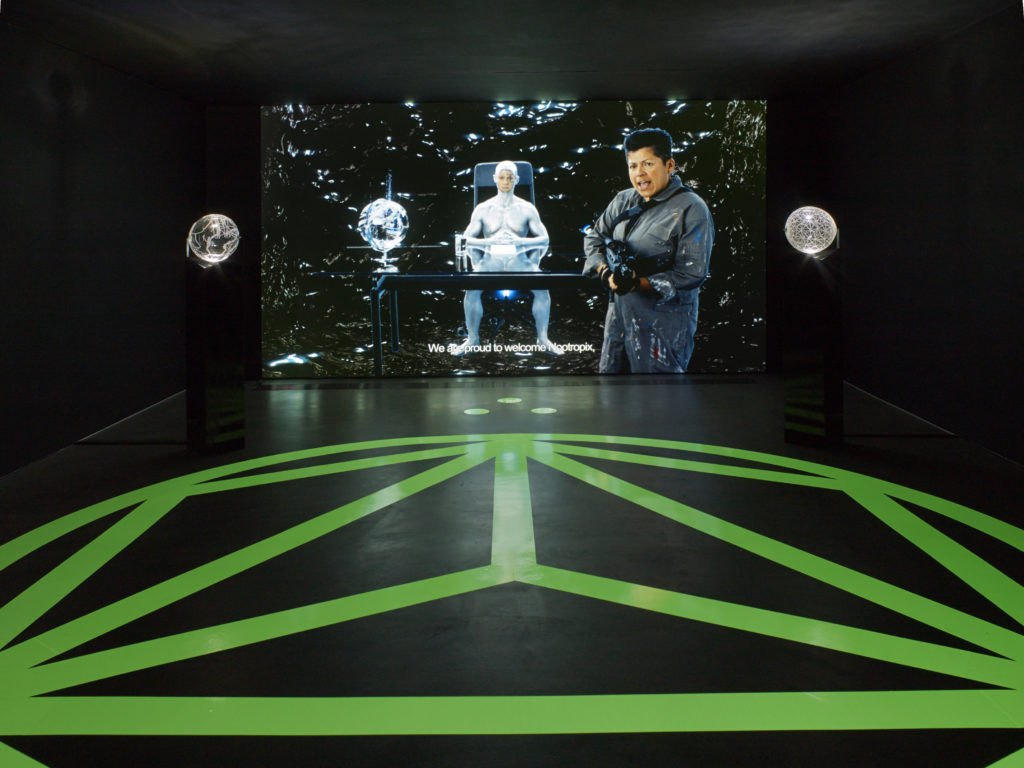

Upon entering the Gasworks space, one is plunged into darkness, where there are two glass spheres resembling crystal balls, each on a black plinth, either side of wall-length screen. They’re meant to evoke the summoning of Silicon Valley tech determinist demons, “The emblem on the floor is supposed to signify a site of conjuring,” Blas says about the installation for a video titled ‘Jubilee 2033’; a queer, contra-capital, sci-fi revisiting of the punk cult 70s film Jubilee. “I wanted to bring in this strange mysticism into the exhibition space as a reference to the original, which starts with Queen Elizabeth with her spiritual advisor, summoning spirits.” The theme of mysticism, superstition, and mind-bending drugs runs through the conversation, as he talks about the power that such ideas have in the world, specifically in relation to data analytics companies that consciously brand their technology as magic. “So it’s thinking about the queer interest that Derek Jarman had towards mysticism in the original, and now this data analytics mysticism that has emerged today. The work tries to hold both these ideas together. So, yeah, drugs and mysticism — they’re there.”

In earlier work, Blas examines the politics of data-driven practices that largely tout themselves as objective, due to machinic intervention, but serve to ‘capture and control,’ as he explains, and ultimately amplify pre-existing biases. In the era of surveillance, with technology that constantly permeates our lives, data is power. “He’s pretty conservative and an active supporter of Trump,” Blas says about venture capitalist Peter Thiel with whom he has a particular fascination. “He famously said that freedom and democracy are no longer compatible. It’s just interesting to think about a data analytics company that does certain technical work for certain political reasons, conceptualising themselves around magic, around doing something mystical. More so, Thiel’s company Palantir has derived its name from the all-seeing crystal ball in Lord of the Rings, essentially presenting their work in data analytics as magic.” Mirroring this information, Blas calls the two crystal ball-like spheres in the installation, Palantirs too. “This thread of mysticism running through the exhibition fits into the whole Silicon Valley mindset. It’s about gazing into perfectly transparent devices and seeing everything through it.”

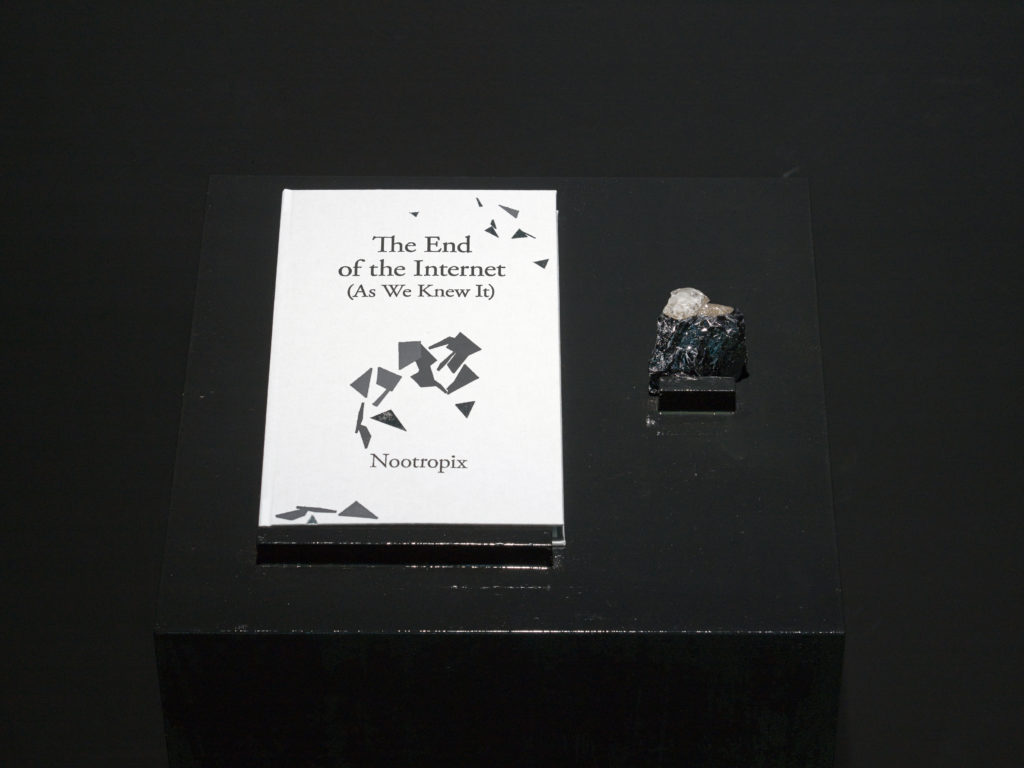

In Contra-Internet, too, the ‘internet’ is used interchangeably with capitalism, referencing the ‘Internet of Things’ or a complex networked compatibility that is present in the world we see. To exemplify this, Blas produced The End of the Internet (As We Knew It); a single edition publication that is a reference to/ ‘utopian plagiarism’ of The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It) by the feminist theory duo J.K. Gibson-Graham. This simple, but effective video plays a didactic role. “I think of these little performance videos as working out a concept, idea, or tactic. And I was really drawn, in ‘Inversion Practice’ series, to this idea of a futuristic, sci-fi effect of being in the space of a laptop and being forced to think about that, aesthetically as a space of certain kinds of logics, where the digital becomes a starting point.”

Similarly, Blas dissects the techno-utopianism of the 90s that has been adopted by Silicon Valley tech entrepreneurs, and their running branding strategy of making the implicit comparison of technology to magic. “[‘Jubilee 2033′] really began with two research questions. One was how and why did the internet make this transition from a place of political possibility from the 90s where the World Wide Web is getting distributed and there is the proliferation of cyberpunk and cyberfeminist work, a place of potential liberation. And today that’s just clearly not where we’re at,” Blas rolls his eyes, “The other question I was interested in was that why is it so hard to imagine an outside to the internet? Why is it that when you Google Image search ‘the Internet,’ you get the world?”

The internet and capitalism run parallel in their sense of totality thwarting the notion of an outside. “At the World Economic Forum in 2015, the previous Google CEO, Eric Schmidt was asked to predict the future of the internet, and he said that it would disappear,” Blas says, “What he meant by that was that the internet would disappear into the world, and there would no longer be a separation between the two. That particular idea is swirling around a lot in this project.”

An important reference point in ‘Jubilee 2033,’ meanwhile, is the 1995 essay ‘The Californian Ideology‘ by Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron, that characterise Silicon Valley as a mix of cybernetics, free market economics, and counter-culture libertarianism. “Originally this film was going to be a documentary, which is funny, because this is not that,” Blas jokes. Instead it brings together a queer/camp sensibility in terms of humour and songs referenced, not to mention a fully queer cast. The storyline follows Ayn Rand (played by legendary queer actor Susan Sachsse) and two other members of the Ayn Rand Collective — Alan Greenspan and his then ex-wife Joan Mitchell — meeting in New York City in 1955. They then take LSD (in a scene hilariously titled ‘Objectivist Drug Party’) and are guided into a techno-accelerationist future by an AI fembot, named Azuma.

“It’s not exactly a realist film but it definitely begins from a realist point. The characters that I chose are historically the people with whom she would meet. Every week Ayn Rand would meet with the rest of her Collective, while she was writing Atlas Shrugged,” Blas explains, “I highlight this to examine different political programs and their relationship to the world, and of the internet being attached to one of them.”

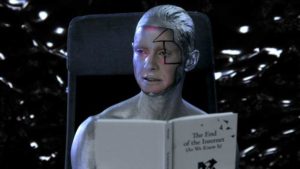

Blas talks about the playful and humorous references to Silicon Valley’s connection to mind-bending substances and mysticism that are littered throughout the exhibition. Like the queer, contra-sexual AI prophet Nootropix (played by Cassils) is a reference to ‘nootropics’; smart drugs or cognitive enhancers. Including LSD, smart drugs are consumed in microdoses to increase work capacity in Silicon Valley, an example of accelerationism in the social sphere. Looking at the etymology of ‘nootropics’, it quite literally means ‘mind-bending.’ “The play on this was not an obvious ‘take drugs and hallucinate’ but more that it’s mind-bending to have this militant, utopian vision of something that is beyond the internet.” Using the classic device of sci-fi dystopia, the film allows us to re-address our own reality.

Azuma’s character is particularly interesting as she is a real AI chatbot that is currently available for pre-order. Seemingly straight out of an episode of Black Mirror, she embodies the gender divide within Silicon Valley and beyond. “I’m interested in Azuma because she’s the first commercial AI that’s a servant or assistant with a full body. Conjuring Azuma allows Rand to encounter this vision of a hypersexualised femme who is also programmed to be a servant. There’s a racialised aspect to her as well, and the first scene is essentially about awful white people who are extremely conservative. Even in Silicon Valley there is a racialisation based on labour. A work that focuses on this is Andrew Norman Wilson’s ‘Workers Leaving the Googleplex.’”

The film ends with Nootropix mirroring Atlas holding the world, before bursting into a joyous dance in a William Gibson version of cyberspace, with Andrea Bocelli’s ‘Con Te Partito‘ as soundtrack to the scene. Blas talks about his fascination with the fact that this is Elon Musk’s favourite song. “I’m very interested by what he had to say about it — that it captures the essence of beauty in the world. And that’s another evocation of the world, so I decided that this has to be the song,” Blas tells me, excitedly. Cheerfully speculative, Blas goes on, “I also made this work in April about this AI chatbot Tay with Jemima Wineman, and we were really interested in Google’s Deep Dream, thinking about it as Silicon Valley psychedelia.” Through speculative realism, Blas likes finding moments in time where something could have potentially happened, and using these moments of possibility to fuel his projects. “It’s interesting to think things through with technologies that have these concepts embedded, and continuing the train of thought that has already been started with them.”

“It’s fun to play with history, and think of the time this takes place in 1955, when Alan Greenspan got his first job at the Federal Reserve, and at the same time the CIA were conducting secret mind control experiments with LSD. So if you want to play with history, this is the time that Alan Greenspan could’ve gotten access to LSD.” The instance of the ‘Objectivist Drug Party’ becomes a fleshing out of potentiality, “I love trying to flip this image so you can see that there is something incredibly psychedelic happening in Silicon Valley.” Blas’ focus on this junction between technology and mysticism shifts the idea of data-driven practices as being inherently objective. Palantir Technologies isn’t an isolated occurrence as there are other examples of this phenomenon. “For example, there was an NSA programme that was called MYSTIC. Why it is that tech companies present themselves in this way? They evoke magic repeatedly — and in giving it a name, you start to understand it more precisely, as a working process.”

The use of large quantities of data in a predictive capacity can be seen as the logic behind Blas’ notion of using transparent devices to see everything. Eric Schmidt’s prediction seems to already be in motion and now ‘bursting out,’ as Blas calls it, with Facebook, Google and Amazon to name a few, (and with an unimaginable combined amount of data on individuals’ habits and preferences) emerging from the internet into the physical world with real estate, facial tracking devices, and more.

In a play between the dichotomy of transparent devices and opacity of material, there’s a Silicon chunk placed within the installation, next to the single edition of The End of the Internet (As We Knew It). “It’s totally opaque, and feels kind of geological. And it’s also at the heart of so much technology today. And what does it mean to gaze into that? Not to seamlessly predict the future, but to use this moment to meditate on the crisis of the present.”

Interested in politicised network alternatives that fracture or challenge the overriding infrastructure of the internet, Blas is still hopeful in the consideration of alternatives to the internet. “There are politically-driven infrastructure projects going on right now, which are about getting out of the commercial internet as we know it. I took a lot of motivation from those — they’re actually art!” While these alternatives are still limited and local, such technologies have been developed in different parts of the world, during large-scale protests or for community social justice projects. “For me, it is believing in an alternative to emerge, and part of that argument is that if you don’t actually believe there is an outside to capital, then you will never achieve that anti-capitalist alternative that you’re supposedly invested in.”**